By Colleen V. Chien, Professor of Law; and Jonathan Collins, Zachary J. Daly , and Rodney Swartz, PhD, all third-year JD students; all at Santa Clara University School of Law. This post is fourth in a series about insights developed based on data released by the USPTO.

“To truly advance innovation and human progress, we must all work to broaden the innovation community and make sure everyone knows that they, too, can change the world through the power of a single idea.”

– June 17, 2020 USPTO Director Andre Iancu

As we wait for a life-saving COVID vaccine, each new day reminds us of the inequalities that the pandemic has laid bare. 30% of public school children lack internet or a computer at home, making school reopenings an urgent priority. Black and brown people, are dying at a much higher rate from Covid due to a complex set of factors, and are at higher risk of lacking access to prescription drugs because of cost.

Though only one part of the larger innovation ecosystem, the patent system has an important role to play in advancing inclusive innovation. Below we build on the USPTO’s recent leadership and the AIA’s recent inclusionary policies (regional offices, pro se/bono supports, fee discounts) to provide a few ideas: being a beacon for the innovation needs of underrepresented populations, addressing the patent grant gap experienced by small inventors, diversifying inventorship by diversifying the patent bar, and developing and reporting innovation equity metrics. These ideas draw upon the paper by one of us, Inequalities, Innovation, and Patents and earlier work, and the ongoing efforts at the USPTO to “broaden the innovation community.”

Be a Beacon for the Unique Innovation Needs of Underrepresented People and for Tech Transfer

Historically, innovation for underrepresented and underresourced groups has been underfunded. For example, Senator and VP candidate Kamala Harris recently introduced a bill to fund research on uterine fibroids, which, though receiving scant research attention, disproportionately impacts African-American women at a rate of 80% over their lifetimes. Closing the broadband access gap will require innovative technology solutions to deal with the “last mile” problems that face rural and underserved populations. The USPTO can use its powers to accelerate innovation to meet the unique needs of underrepresented and underresourced groups, including, as was done in the context of the Cancer Moonshot initiative, identifying relevant patents and applications and combining patent data with external data sources for example from agencies like the National Institutes of Health and Food and Drug Administration. These efforts bring connect patented inventions to “upstream funding and R&D as well as downstream commercialization efforts.” To speed COVID innovation, the agency has taken a number of other steps including deferring or waiving fees, prioritizing examination, and launching a platform to facilitate connections between patent holders and licensees. These capacities could be directed to priority equity areas, which are positioned to benefit especially when private and public funding is at stake.

Expand Equality of Opportunity by Addressing the “Patenting Grant Gap”

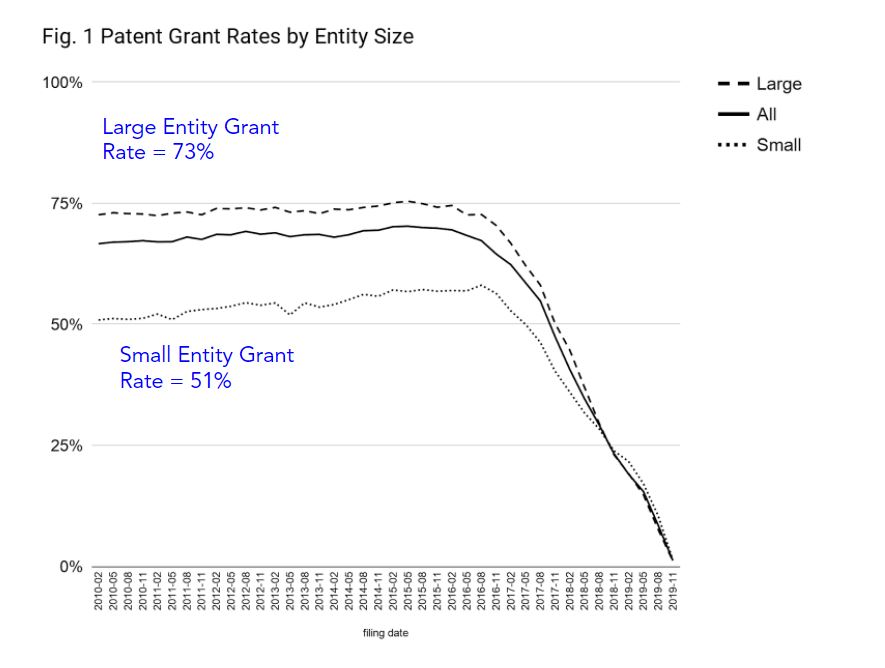

When startups and innovation entrants patent, good outcomes often follow: first-time patenting is associated with investment, hiring, and economic mobility. But in many cases, the applications submitted by small entity inventors don’t actually turn into patents. Using open government data helpfully made available by the USPTO Open Data Portal (beta) we find, as documented in Fig. 1 below from the paper, that small entities are less likely to succeed when they apply for patents: by our estimate, applications filed 10 years ago have turned into patents 73% of the time vs. 51% for small/micro entities, a 40%+ difference.

Others including work by former USPTO Chief Economist Alan Marco, have reached similar conclusions. Empirical studies have also found that inventors with female sounding names, or who are represented by law firms that are less familiar to patent examiners are less likely to get patents on their applications than their counterparts.

The difference in allowance rates may be due to any of a variety of factors, for example, a higher abandonment rate or differences in the types of patents sought. The possibility of implicit bias – based on inventor, or firm name – is also worth investigating further; the USPTO isn’t the only federal agency where the possibility of bias has been documented. But no matter the reason, ungranted applications to underrepresented groups present not only potential equity problems for society but also economic problems for the agency: applications that never mature into patents don’t generate issuance and maintenance fees.

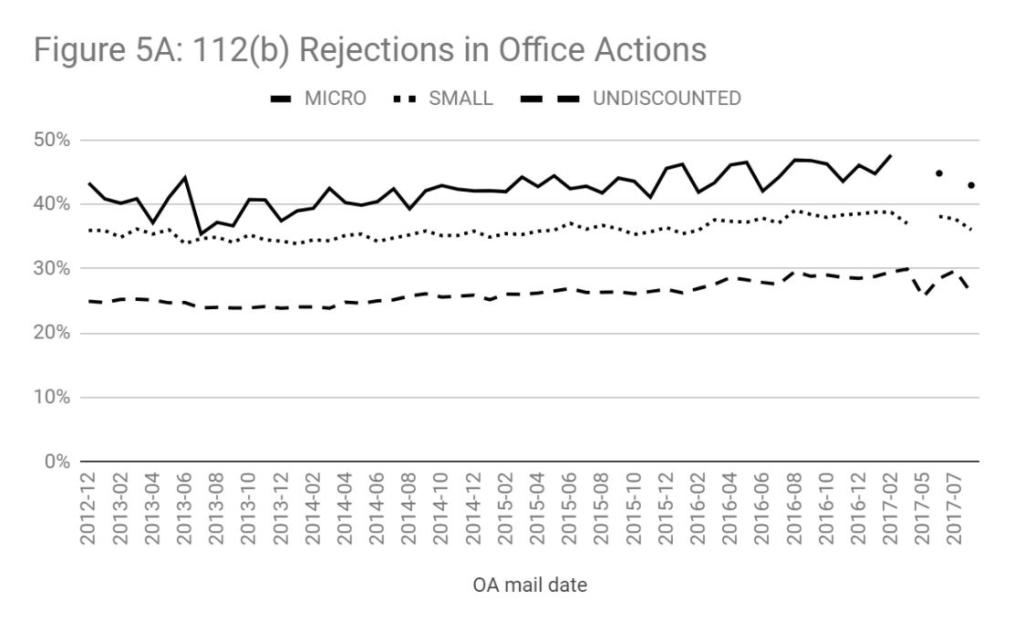

One solution may be to try to improve the quality of underlying applications. As previously documented using PTO office action data, the applications of discounted entities are much more likely to have 112 rejections, and in particular 112(b) rejections. (Fig. 5A) A lack of “applicant readiness,” as described by examiners, may be one culprit.

A promising approach as discussed previously by one of us would be to democratize access to drafting tools and aids, which are often used by sophisticated applicants to, for example, check the correspondence between claim terms and the specification. Using error correction technology to level the playing field in government filings, through public and private action, is precedented. Improved application quality advances the shared goal of compact prosecution, and to that end it is encouraging to see that the Office of Patent Quality Assurance, in their ongoing work to improve applicant readiness, is reportedly working to “identify opportunities for IT to assist with quality enhancements early in the process.” Such efforts could go a long way to address both the equity and economic challenges described above. We encourage continued investigation and prioritization of public and private efforts to address the “patent grant gap” in support of broader inventorship and participation in innovation.

Diversifying Inventorship by Diversifying the Patent Bar

As argued in the paper, patenting is a social activity that depends on social connections -“who you know and who you can call upon.” But access to patent talent is uneven – Sara Blakely, the founder of Spanx, has reported that she could not find a single female patent attorney in the state of Georgia to file the patent upon which she built her billion-dollar undergarments empire. To sit for the patent bar generally requires a science, technology, or engineering degree. But because of their underrepresentation among STEM, engineering, and computer science graduates, women, Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately excluded from participation. The technical degree requirement particularly disadvantages those with design experience but not engineering degrees, who are often women, and who might otherwise want to prosecute design patents over fashion or industrial design, Christopher Buccafusco and Jeanne Curtis have noted. Relaxing the technical degree requirement would enable diversification of the patent bar, in support of diversifying inventorship and entrepreneurship.

Develop and Prioritizing Innovation Equity Metrics and What Works

While each year the number of new patent grants is announced, perhaps the patent statistic that has catalyzed the most action recently is the USPTO’s groundbreaking Progress and Potential series of reports which, for the first time, officially documented that only 12-13% of American inventors are women, and Director Iancu’s leadership and his staff on the issue. This report has prompted conferences and toolkits, and spurred companies to revisit their patent programs and pipelines. As additional resources are invested into making innovation more inclusive, “innovation equity metrics” that take advantage of the granularity, quality, and regularity of patent data, and that track, for example “inventor entry” and “concentration” and the geographic distribution of patents, as demonstrated in the paper, are worth investing in. Improved data collection, for example, of race and veteran status data, and federation and coordination with other datasets, for example held by the Small Business Administration, or in connection with the Small Business Innovation Research program, and Census could go a long way. Doing so would allow for more regular reporting and analysis of the overall health of the innovation ecosystem, which, by a few measures appears to be waning: as described in the paper, patenting by new entrants is down while the concentration of patent holdings is up. Surveys of underrepresented inventors, and what have been enablers and blockers, can also lend inform the development of policies of inclusion.

Conclusion

Though only one part of the larger innovation ecosystem, the patent system’s long-standing commitment to a diversity of inventors and equal opportunity position it well to answer the call of the current moment, for greater inclusion in innovation. We encourage readers with concrete ideas about how to advance inclusion in innovation, through the patent or other governmental levers, to submit them to the DayOneProject, which is collecting ideas for action for the next administration. For more, also check out the recent Brookings Report on Broadening Innovation by Michigan State Prof. Lisa Cook, a leading economist (see, e.g. the NPR Planet Money podcast, Patent Racism, about her work).

The authors represent that they are not being paid to take a position in this post nor do they have any conflicts of interest in the subject matter discussed in this post. Comments have been disabled at the authors’ request.

“But because of their underrepresentation among STEM, engineering, and computer science graduates, women, Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately excluded from participation.”

So, have I been seemingly nefariously “excluded” from participation in surgery because I didn’t get a medical degree? Stop the presses, I’m being horrendously abused because I chose a different career!

Jokes aside, no one’s “excluded” from anything. You want to be a patent attorney/agent? Get a degree for it just like the vast majority of jobs that require college degrees.

” from participation in surgery because I didn’t get a medical degree?”

Nah that’s because you don’t have a license from the AMA. But one of the reasons is likely because you don’t have a medical degree.

“We encourage readers with concrete ideas about how to advance inclusion in innovation, through the patent or other governmental levers, to submit them to the DayOneProject, which is collecting ideas for action for the next administration. ”

I had my response deleted by the system I guess. But it’s super easy. We just make black/brown people file patents and take allowable subject matter in their claims.

Increasing equity is even easier, you oppress the white/asian/India indian people, or you install black and/or brown people as the social superiors of leftists for a Win win.

“The authors represent that they are not being paid to take a position in this post”

False, I just now paid you a virtue point, evil one. You’re going to need to return it at the end of the day however, and start your virtue collection over tomorrow, on account of your evil.

“The difference in allowance rates may be due to any of a variety of factors, for example, a higher abandonment rate or differences in the types of patents sought. The possibility of implicit bias – based on inventor, or firm name – is also worth investigating further; the USPTO isn’t the only federal agency where the possibility of bias has been documented. But no matter the reason, ungranted applications to underrepresented groups present not only potential equity problems for society but also economic problems for the agency: applications that never mature into patents don’t generate issuance and maintenance fees.”

Yeah and then the ebil right wing is just going to the accompanying “other explanations” that correspond to the muh implicit bias etc. that Jason here is not willing to entertain lol. If MM were here, I’m sure he would do his duty and he would remind us that AlL CuLtUrEs are EqUaL (in kindergarten font) etc. etc.

But hey, I wish you gl in proving that the examination corps (likely majority minorty at this point) is liek tots RAYCST U GUIS! You know, when they read an applicant’s name (which is considered super important information when examiners examine a patent! In fact it often determines whether a rejection issues or not!).

“diversifying inventorship by diversifying the patent bar,”

How does that work lol? By what mechanism does the patent bar diversifying affect, in any way, how diverse inventorship is?

“The technical degree requirement particularly disadvantages those with design experience but not engineering degrees, who are often women, and who might otherwise want to prosecute design patents over fashion or industrial design, Christopher Buccafusco and Jeanne Curtis have noted. Relaxing the technical degree requirement would enable diversification of the patent bar, in support of diversifying inventorship and entrepreneurship.”

Setting aside the actual argument presented here, I’m not sure that the technical degree requirement is especially defensible. Most practicioners aren’t capable of practicing across the full breadth of subject areas, and the office relies on them to police themselves as to what material they can prosecute. Why should it be any different for someone with experience in shoe design but no technical degree?

The technical degree requirement should be abolished. It serves no useful purpose.

I would opt for a “critical thinking” requirement.

It would be far better to dampen the ‘sheeple’ effect.

Of course (and I fully recognize that my view on this mat he a bit biased), training in the “hard” areas related to STEM as opposed to the “soft” areas of Humanities does provide better critical thinking skills.

This is most definitely NOT saying that every person trained through STEM has sufficient critical thinking skills, nor is it panning those who came through training of the Humanities as necessarily lacking critical thinking skills, but by and large, the taint of academic rot is far stronger in the “soft” areas.

“Of course (and I fully recognize that my view on this mat he a bit biased), training in the ‘hard’ areas related to STEM as opposed to the ‘soft’ areas of Humanities does provide better critical thinking skills.”

Yes, your view is a bit biased. And wrong. It is merely your opinion. And is not based in any fact whatsoever.

And “critical thinking” is a rather silly amorphous concept that nobody would ever actually agree on.

Really think about what is going on here too.

Rather than looking at individual cases and saying the law was misapplied, they are categorizing people and then complaining that the outcome is not what it should be in a “just” society. So, first they remove our laws with Alice/Mayo/KSR and so forth so that there is no way to say whether any application of the law is fair or unfair as the trier of fact has almost complete power to decide the case either way. And, so the solution is to keep statistics and put us each in a category and demand that the outcomes are proportional to what they think they should be.

Really think about what they are doing. It is stomach turning to any person that loves the law.

So the outcome of your case will depend on how other people in whatever category they put you have done recently so that they can keep the statistical outcome in accordance with the prescribed percentages.

Really think about the alliance of the totalitarian left with the monopolistic corporations of SV.

I believe that I was the first in the blogosphere to point out that patents were under attack from how I characterized it, the Left and the Right*.

(and noted that the ‘Right’ in my characterization did not fully coincide with the political Right, but instead reflected the Big Corp, often Multi-National Established entities that reflect the Efficient Infringer group)

I pointed this out YEARS ago.

Welcome to the identity politics gambit of Neo-Liberalism.

“Rather than looking at individual cases and saying the law was misapplied, they are categorizing people and then complaining that the outcome is not what it should be in a “just” society.”

I am not impressed by the analysis here, but I don’t see how they’re doing what you accused them of doing. They are not drawing conclusions for individual cases based on the aggregate. Instead they’re suggesting how the aggregate should look. That may be wrong, but it’s far from what you describe.

There was one sentence in this article that warrants additional attention:

“Empirical studies have also found that inventors…who are represented by law firms that are less familiar to patent examiners are less likely to get patents on their applications than their counterparts.”

There is a reason that some law firms are “less familiar to patent examiners”. They are filing and prosecuting fewer applications than the big firms. Those big firms have more experience because they prosecute more applications. This in turn would make them better at it because they know how best to advance an application through to allowance. The experience of the attorney (and their familiarity with the technology) play a huge role in whether or not an application gets allowed. The bigger more experienced firms will usually cost more also. Smaller clients and solo inventors are often (not always) less well funded than the large entities so they would seek to hire the less expensive, and possibly less experienced, attorneys. There are definitely some small firms that are extremely good, no doubt about that, but this is discussing general trends. It seems like the old adage of “you get what you pay for” might be be relevant to this data also.

Dvan, thanks for your input, and it reminded me of another major reason large companies have higher grant rates than private inventors. Well-run large companies have independent expert committees deciding what ideas to file applications on, including prior art and commercial realities. In contrast, private inventor filing decisions are too often affected by personal pride of authorship.

Paul, that is definitely another significant issue I had not considered. When I get invention disclosures from my large clients, it is not uncommon that their in-house people, even if not patent attorneys, have already considered claims, scope, etc. which makes drafting much easier. They have definitely done a thorough review of the invention. If they don’t have a novelty search in hand, then that is often one first thing they have me do before writing. I had a solo inventor one time that I convinced to spend the money on a novelty search. I found his invention for sale on Amazon. It wasn’t pretty after that. It did however convince him that he wasn’t wasting his money on lawyers and that (at least some of them) know a little bit about what they are talking about. Nothing worse than getting an Office Action back with multiple 102 rejections perfectly on point that the inventor knew nothing about.

Agree completely with both Paul and you.

Also, large patent firms are more likely to interview examiners before second actions, and know how to do so effectively.

Absolutely agree with this as well.

“There was one sentence in this article that warrants additional attention:

“Empirical studies have also found that inventors…who are represented by law firms that are less familiar to patent examiners are less likely to get patents on their applications than their counterparts.””

I too thought this was a noteworthy sentence.

It seems genuinely bizarre to me to construct this as ‘firms that are less familiar to examiners’ rather than ‘firms that have less experience before examiners’. I suspect that examiners and practicioners alike would agree that the impact of practicioner experience dwarfs any impact of examiner-practicioner familiarity.

Good grief. Women sounding names? Reminds me of the punchline of the old joke about the asteroid about to destroy all life on earth: Washington Post War headline font: Asteroid on course to destroy all life on earth Women and minorities effected most.

Yeah, iwasthere, the world has gone insane.

If and until such time that Congress and / or our Supreme Court restore full patent eligibility to all inventions — regardless of the field of innovation — such opportunity and access will continue to be blocked; including for those most in need of American opportunity and access.

“Comments have been disabled at the authors’ request”

Thanks for clarifying this.

Women, minority, and veteran inventors who testified at USPTO SUCCESS Act hearings stated that difficulty with enforcement and likelihood of PTAB invalidation were barriers to their participation in the patent system. One witness summarized, “What good is a patent, if one cannot defend it?”

link to usinventor.org

It is disgusting to watch the USPTO, Commerce, Congress, and academics like the authors continue to ignore this fundamental problem. Instead they have increased the marketing campaign to trick more would-be inventors to waste their time and money on phony patents.

These people are at San Jose and are in the pocket of SV.

These are people that Lemley got positions at universities. As far as I can tell the SV corporations are giving money to the universities and are controlling the hires so they get f i l t h like this.

Curious as to the % of small entity applications that are pro-se or via “invention promotion companies”?

Also, as previously noted, some large IPL firms will no longer handle patent application prep and prosecution from individual inventors, with concerns such as payments, excessive time required, safety, possible conflicts, need for prior art searches, the large amount of prior art in some of the invention subjects of private inventors, etc.

And because it is unethical to take money from inventors for phony patents that are not “the right to exclude” and that the attorney will not warrant against PTAB invalidation.

Would you really want an attorney that is so out of touch that she would warrant against PTAB invalidation?

+1

Paul, you make a point that had not occurred to me: that it can be more trouble than it’s worth, for established firms to accept instructions from individual inventors.

Even in the mainstream professions, say, dentist or criminal lawyer, it is devilish hard for a lay person to find a safe and satisfactory practitioner. How much harder it must be, to find a patent attorney whose services are well-worth paying for.

Do any of the big firms offer patent search and drafting services pro bono? There is nothing like real cases to educate and train entrants to the profession.

From Europe, and thinking about access to the patent system by individual and impecunious inventors, a question:

Patent applications drafted in the USA used to be compact, often just a few pages of text. Now, they are invariably enormous, seemingly repetitive, otiose, over-blown. One sees this in, for example, search report references: the old ones are compact, the recently published ones astonishingly wordy. Not so, elsewhere in the world, where specifications are often still compact. Why is this (I do know why but perhaps I’m wrong)? I wonder, does it burden private clients with excessive fees for patent drafting? Does it result in “entry fees” within the USA that are more intimidating than elsewhere in the world?

MaxDrei,

Rather than asserting that you know why, maybe start a dialogue as to what you think it is and why you think it is.

It would be a far more interesting post than the one you provided.

Max, we are forced to write the applications like this because of 112 and 101.

In fact one of the tests of 101 is how well the claims are engrained in the technology so you have to include all sorts of details.

And, please, I am not going to get into the case law, but the wa nk ies like Taranto at the CAFC have done everything they can to trash any patent that doesn’t include all sorts of extraneous information.

It’s called ‘patent profanity,’ and MaxDrie has seen comments to this effect previously (I know, because I am one of those that have made such comments to MaxDrie previously).

Again, it would be a better conversation if he instead of saying “I know” — but withheld what he thinks he knows — actually shared the “what” and the “why.”

He might get a critique of his views, and it is most probably his not wanting to put his views under a microscope (can’t look too carefully there) that prompts MaxDrie to post as he posts.

Indeed. Patent profanity, unique to the USA, in consequence of the court-made law under two statutory provisions, 101 and 112, that contain problematic language unique to the USA.

So who to blame for the profanity? The legislator, those who instruct lobbyists, the courts, the media, or the patent attorneys?

I think I ought to refrain from apportioning blame but nevertheless I hold responsible the legislative and adjudicative branches, in roughly equal measure. Shame on them both.

Well how about that – I (mostly) agree with MaxDrie – on several levels.

I would though put a touch more blame on the Judicial Branch, as they are often the originators of the profanity in their hubris of legislating from the bench.

Keep in mind that it is always a proper avenue of the judiciary to throw out a law that it not clear enough.

New add: “Comments have been disabled at the authors’ request.”

These likely won’t be left around too long.

Interesting. Do any of these imaginary “colleagues” that pay you to post have names?

?

The question of the moment: will my pal Shifty own his control of the ‘why?’

I wonder what reactions would be drawn if Figure 1 went back to capture the “Just Say No, look at our high quality” drop into the 30% allowance range in the circa Dudas era…

Oh goodness. One of the architects of dismantling the patent system is now telling us how to promote innovation. Goodness. Goodness. Goodness.

Comments are closed.