by Dennis Crouch

In re: Infinity Headwear & Apparel, Docket No. 18-01998 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

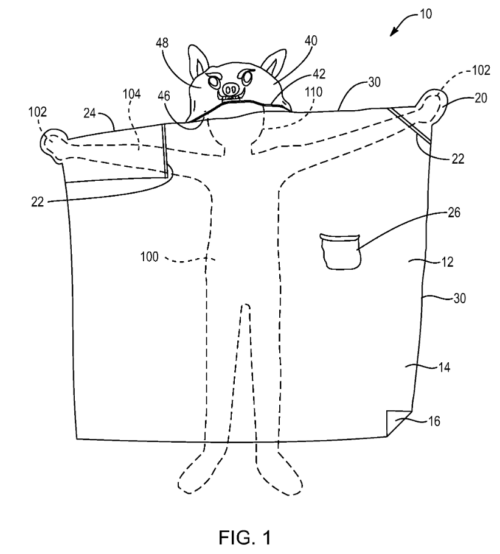

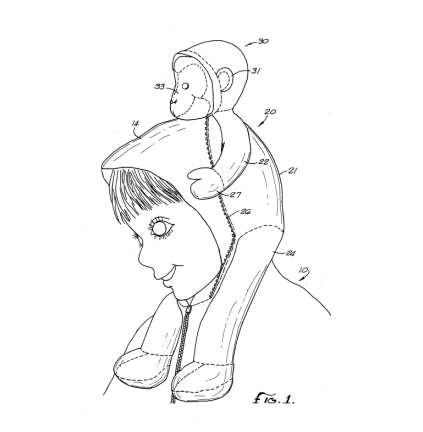

This case is fairly silly – The claims at issue cover a hooded blanket and stuffed toy combination — found invalid reexamination. On appeal, the patentee argued that the PTAB had conducted an improper claim construction that “equated a monkey with the claimed hood.”

Unlike the present invention, however, Katz’s hooded jacket includes a stuffed monkey attached to, or forming, the back portion of the hood. . . .

[U]nlike the present invention where the hood itself forms the stuffed toy, Katz’s hood is stuffed into monkey to form the stuffed toy. Also, in Katz, a stuffed toy always exists because monkey, which includes separately stuffed arms and legs, is sewn to the back portion of hood. In contrast, in the present invention, no stuffed toy exists until blanket is stuffed into hood.

Invalidity affirmed on appeal (R.36). Images from the invalidated patent and the key prior art (Katz) are shown below.

Yes, I am aware that this case – especially as whimsically presented here – pushes against my call for the Federal Circuit to actually write opinions. The PTAB decision is based upon anticipation, and the patentee provided a series of explanations regarding the distinction between its claims and the single prior art reference. I suspect that the Federal Circuit would actually have a difficult time penning the anticipation case even here.

. . . and yet I find nothing at all about any of this in the Monkey Arts . . .

I’m most concerned about the demonic eyes on that kid…

No kidding. That drawing is macabre.

Guys, it’s not a real kid. It’s a stuffed kid for your pet monkey to play with. Look at the picture: that monkey is loving it.

…opportunity for the trademark SkullFuct…?

RE: “The PTAB decision is based upon anticipation, and the patentee provided a series of explanations regarding the distinction between its claims and the single prior art reference. I suspect that the Federal Circuit would actually have a difficult time penning the anticipation case even here.”

It seems to me that a rejection on grounds of anticipation or lack of novelty inherently includes an obviousness rejection within it. Therefore, to overcome the rejection, it would be insufficient by itself to simply point out differences vis-a-vis the prior art without also arguing why those differences would have rendered the claimed subject matter as a whole nonobvious. Arguing differences is a necessary first step to overcoming anticipation, but must be followed up with a more complete argument of patentability on grounds of nonobviousness. Compact prosecution before the USPTO would seem to demand it, and I don’t see why it would be any different on appeal.

No. If the Office meant obvious, it should reject under 103. We have enough conflating of the statutes as it is.

No. The Examiner thought there was enough for anticipation, so the rejection should be under 102. That doesn’t mean that only differences arguments should be sufficient to overcome it.

By analogy, if a prosecutor thinks there is enough of a case to prove murder, you don’t charge only manslaughter; but the lesser included offense is still there, inherently underlying a murder charge if the jury doesn’t find the requisite state of mind to have been proven.

” That doesn’t mean that only differences arguments should be sufficient to overcome it.”

Yes, yes it does. There is more to an Obviousness rejection than just citing the document. An Examiner must explain why it would have been obvious to make the requisite changes. If there is an obviousness argument to be made. It should be made.

“By analogy, if a prosecutor thinks there is enough of a case to prove murder, you don’t charge only manslaughter; but the lesser included offense is still there, inherently underlying a murder charge if the jury doesn’t find the requisite state of mind to have been proven.”

My point exactly. Additional charges are applied. The additional charges are not merely implied.

“seems to me that a rejection on grounds of anticipation or lack of novelty inherently includes an obviousness rejection within it.”

This evidences a profound lack of understanding of patent law.

35 U.S.C. 103 A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained, notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed as set forth in section 102, if …

The very wording of the obviousness statute implies that anticipation is the epitome of obviousness. If proof of anticipation fails because not all elements can be found in the cited reference, a mere technical defense that there are differences is not sufficient to show patentability. Yes, novelty is an different condition than obviousness, but novelty does not amount to patentable invention if it would also have been obvious in light of the same cited reference.

Fine, but §102 also says “shall be entitled to a patent unless…” (emphasis added). That “unless” conveys that the default state is that the applicant gets the patent unless the PTO makes out a prima facie rejection. If the PTO makes out a prima facie rejection for anticipation, and the CAFC shoots it down, then that is that. There is no record §103 rejection (other than the one that has already, ex hypothesi, been vacated by the CAFC) for the applicant to address. Nor has the CAFC any sort of institutional capability (or legal jurisdiction) to advance or adjudicate such a rejection.

You make a good point regarding the record below as to why procedurally it must be different on appeal (at least to the courts).

But what a waste of client money to have to go through a second round of examination arguing obviousness on remand back at the PTO in order to further develop the record. The alternative is for the PTO to close prosecution and issue an invalid patent. A better and less expensive practice is to properly develop the record on all relavent grounds before the Examiner the first time.

At one time, Examiners could (and sometimes would) reject claims under 35 USC 102 and 103 in the alternative; but this seems to be very rare or no longer the case, even though examinations are supposely required to be “complete” as to compliance with applicable statutes and patentability of the invention as claimed. (37 CFR 1.1.04)

Your quote distinguishes 103 from 102 – the opposite of what you are trying to portray.

Again – your grasp of basic patent law is abysmal here.

“At one time, Examiners could (and sometimes would) reject claims under 35 USC 102 and 103 in the alternative”

They still can. But most of the time, one or the other is more appropriate than both in the alternative.

The alternative is for the PTO to close prosecution and issue an invalid patent.

I am not sure that this is even an option really. The rule is supposed to be that once the PTO loses in front of the CAFC, they are supposed to issue the patent, not reopen prosecution. In re Van Os, 844 F.3d 1359, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (Newman, J., concurring). Sadly, this is recently become a rule more honored in the breach than the observance.

[W]hat a waste of client money to have to go through a second round of examination arguing obviousness on remand back at the PTO in order to further develop the record… A better and less expensive practice is to properly develop the record on all rel[eva]nt grounds before the Examiner the first time.

Sure, no argument there. Much better to put the right rejections on the record, rather than the wrong ones, so that the case might be correctly decided. In a world run by humans rather than angels, however, some number of mistakes (even expensive mistakes) are simply inevitable.

At one time, Examiners could (and sometimes would) reject claims under 35 USC 102 and 103 in the alternative; but this seems to be very rare or no longer the case…

Really, is this rare in your experience? Quite the opposite in mine. I would say that—of the office actions that I see that include an anticipation rejection—there are more that also include an explicit obviousness rejection in the alternative than office actions that only make the anticipation rejection. In other words, in my experience (mostly art units in the 1600s), examiners usually make the 102/103 rejections in the alternative. As you say, this seems to me a good practice for compact prosecution.

The alternative is for the PTO to close prosecution and issue an invalid patent.

I am not sure that this is even an option really…

Whoops, sorry. I quoted the wrong portion from your 4.2.1.1.1. Closing prosecution and issuing an (arguably) invalid patent is the only option (or, at least, it is supposed to be the only option) after the PTO loses in front of the CAFC. I had meant for my 4.2.1.1.1.3 to begin:

It seems to me you know nothing of patent practice. Or logic.

If the PTO or patent challenger wishes to present a case for obviousness, then it must set forth that case. Otherwise the applicant/patentee doesn’t know what to respond to. That’s just basic civil procedure.

Absolutely, AM.

(That’s in addition to the plain fact that a 102 rejection is simply NOT a 103 rejection – “inherent” or otherwise).

What a relief! A precedential case might have impacted my claims to a method of using artificial intelligence to determine the most subjectively convincing positions for attaching animal ears to hooded apparel.

The Ends justifies the Means…

In Russia, monkey stuffs you.

Comments are closed.