Andrew Metrick is the Janet L. Yellen Professor of Finance and Management at the Yale School of Management and the Director of the Yale Program on Financial Stability; and Paul Schmelzing is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Yale School of Management. This post is based on their recent paper.

Banking crises are pervasive. Even mature economies with stable governments cannot escape them. These crises are costly for economies, for public trust, and for political stability. These social costs motivate government action, but what form should that action take? What kinds of interventions work? How exactly should they be structured and sequenced? To answer these questions we would like to learn from history, and to do this well requires a database of past actions. Despite considerable progress by scholars since the 1990s in building chronologies of banking crises, no comprehensive overview cataloguing and analyzing crisis interventions exists. In a newly released working paper, we present such a comprehensive database for the first time, describe our construction process, and analyze the patterns of crisis interventions across time and space. A dedicated database website (to be updated regularly) contains full documentations, bibliographies, and excel sheets for researchers and the general public.

To construct our database we first compiled a master list of canonical crises from four major crisis-chronology projects: Reinhart and Rogoff (2009), Schularick and Taylor (2012), Laeven and Valencia (2020), and Baron, Verner, and Xiong (2021). The union of these four sources includes 494 canonical crises. Next, for each canonical crisis, we consult the sources cited by the original authors, along with an extensive primary and secondary literature. These two steps yield a list of 1187 specific interventions.

The same sources used to identify interventions during canonical crises often have evidence of interventions taken at other times. These additional interventions can show up in the historical records for several possible reasons. In some cases, such interventions may have successfully prevented a major crisis, so that existing crisis chronologies do not have an event at that time. In other cases, such interventions may be trace evidence of a crisis that did occur but was not detected by the methods of the canonical papers. This additional step adds an additional 699 interventions, which are grouped temporally and geographically into 408 candidate crises. 112 of these candidate crises (associated with 164 specific interventions) occur before 1800. One reason to extend the scope in this way is that the existence of an intervention may be a sign that there was indeed a banking crisis that was overlooked by the past literature. But perhaps more intriguing is the possibility that such interventions played a role in successfully preventing an incipient crisis, and those would certainly be interventions worthy of further study. In sum, the current version of the database includes 1886 interventions since the 13th century, starting with a series of emergency banking sector interventions in Genoa in January 1257.

Our paper is most closely related to Laeven and Valencia (2020), one of the four chronologies that constitute the set of canonical crises we use. Laeven and Valencia cover countries across all income groups and—setting the work apart from similar chronologies—also systematically document crisis interventions associated with 151 crisis events across seven major intervention categories: the Laeven and Valencia paper focuses on patterns of financial crises in the post-Bretton Woods period, of which they study 151 cases in-depth. Our focus, on the other hand, is on the interventions themselves, even when such interventions occur outside of previously identified crisis periods.

As an operating framework for our database, we introduce a classification system for banking-crisis interventions: the classification system is mapped onto the financial-sector balance sheet and includes 20 types of interventions in seven major categories.

In particular, in a crisis, a weakness of bank (or other intermediary) balance sheets carries negative externalities for other parts of the economy or the public sector. In the acute, panic, phase of a crisis, concerns about bank solvency can induce short-term creditors to run on the bank, decreasing its ability to sustain its liabilities. The traditional lender-of-last-resort (LOLR) function of central banks is just a direct replacement of such liabilities. If the panic has been driven by some short-term dislocation of markets, then such emergency lending may be all that is necessary. In cases where the government is confident of the ultimate solvency of banks but still concerned about future runs, then a more drastic action would be to extend guarantees to liabilities beyond any existing deposit insurance, an option widely deployed in the 2008 financial crisis.

If bank-solvency concerns are real and lasting, the government can move down the right-hand-side of the balance sheet and provide equity through capital injections, which could reassure depositors of solvency and reduce the incentive to run.

In some cases, the solvency of the banking system is threatened by the concentration of certain kinds of assets, and banks face a coordination problem in exiting or restructuring them. In those cases, governments often move to the left side of the balance sheet through asset management programs, which can solve the coordination problem. When banks are clearly insolvent, the government may still have a role to play in the restructuring of these failed institutions. Both of these intervention groups represent typical “modern” policy responses according to our data.

Each of the categories listed thus far would typically include some outlay or contingent commitment from either the fiscal or monetary authority. But other types of interventions instead use government’s power to change or suspend rules and regulations. We document that through most of history, bank holidays and suspensions of convertibility were a common feature of crisis response. In the modern era, governments often resort to suspensions of regulatory-capital requirements and to market-based changes like short-sale bans in equity markets. Finally, there is a catchall category of other interventions that do not fit neatly into the six major categories above.

Prior to 1914, about one-third of all interventions were in the lending category, with a further one-quarter of all interventions classified as rules. In contrast, rules changes play a very small role in the 21st century (about six percent of interventions) and lending is about 23 percent. Instead, the largest category in these recent years is capital injections, with about 27 percent of the total. Indeed, this same time-series pattern is echoed in the cross-section, where we find the use of capital injections and guarantees to be positively correlated to a country’s per-capita income level. Overall, our data show that governments have become more aggressive over time, with interventions being increasingly more likely to fall at the bottom of the balance sheet (equity) instead of the top (collateralized lending), and with authorities also increasingly targeting multiple parts of the balance sheet simultaneously.

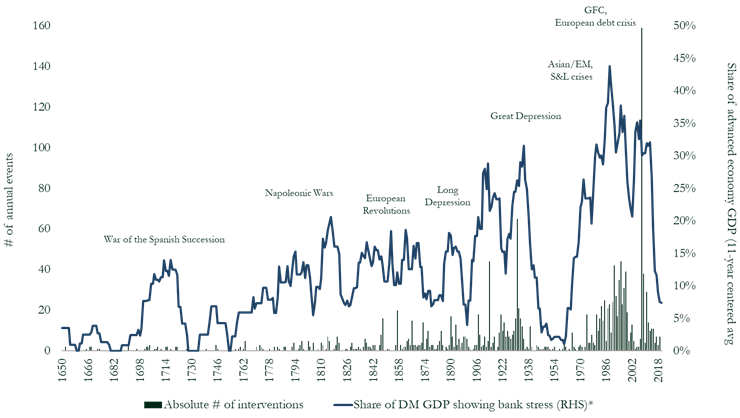

We next calculate the share of advanced economy GDP over time experiencing some form of bank stress in any given year: the series suggests that the four decades since the 1980s represent only the most recent apex in an entrenched trend towards growing absolute intervention frequencies over multiple centuries (visualized in Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: absolute number of banking-crisis interventions, and share of advanced economy GDP experiencing bank stress, annual basis, 1650-2019.

In the historical record, crises are like fires and the government interventions in those crises are firefighting. The way history is written, it is often easier to observe trace evidence of firefighting than to get other indicia of the fire itself. The existing crisis chronologies are built from looking for direct evidence of the fire. This has been an important exercise for the macroeconomics and finance because the historical record is clear about the existence of the most severe crises, and these examples are the most quantitatively important for welfare. But if we are interested in the efficacy of interventions, we also need to study the cases where we observe the firefighting, but no long-term damage apparent from the fire. The main goal of our project is to build a database that includes as many interventions as possible, offering researchers across disciplines a new comprehensive reference to study policy types, patterns, the efficiency, the sequencing, and the sizes of such policy decisions across time and space.

Our data show that governments have become more aggressive over time: measured by number of interventions per crisis, by interventions “moving down the balance sheet” from liabilities to equity, and by a higher likelihood of interventions hitting multiple parts of the balance sheet during the same crisis. We observe the same differences in the cross-section, with wealthier countries more likely to intervene, particularly lower down on the balance sheet. Perhaps most importantly in the long-run context, intervention frequencies and sizes suggest that the recent “crisis problem” in the financial sector actually represents part of a deeply entrenched development that saw global intervention frequencies and sizes gradually rise since at least the late 17th century.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print