Obviousness is the central patentability doctrine. Obvious innovations are not patentable. Instead, to be patentable, and invention must embody a substantial step beyond what was known in the prior art. Unlike its more rigid brother-doctrine of anticipation, obviousness is flexible to its core. This flexibility leaves the doctrine both powerful and subject to many lawyer arguments.

A new petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court asks two seemingly simple questions:

- In making rejections under 35 U.S.C. § 103(a), what standard should be applied in determining whether prior art is “analogous?”

- If the prior art is demonstrated to be non-analogous, does that render any such obviousness rejection void?

Macor v. USPTO, Sct. Docket No. 18-1072.

Although the questions presented may be interesting in the abstract – the actual underlying arguments are extremely weak:

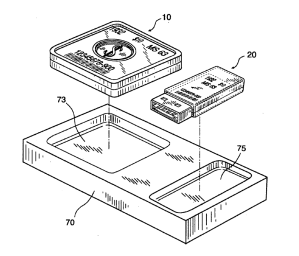

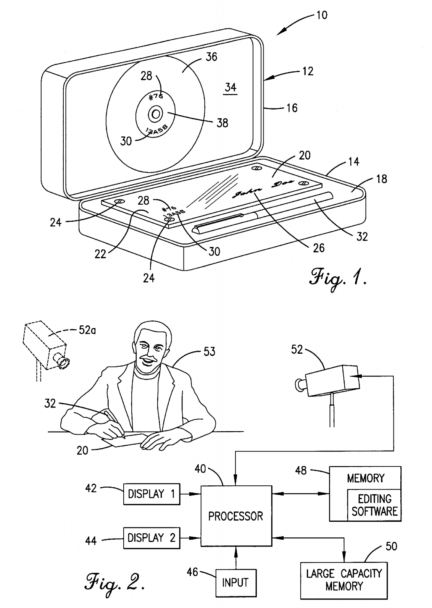

The invention in this case stems from a problem in the collectables market of certifying authenticity. The patent application here claims a FLASH-drive that contains an “immutable digital image” of a collectable (such as a coin). The drive itself will also include “tamper resistant visual markings” that tie it to the particular collectable.

The examiner rejected the pending claims as obvious based upon U.S. Patent No.

6,250,549 (DeFabio) both alone and in combination with other references.

DeFabio is also focused collectable authentication — particularly celebrity signatures. That patent discloses the idea of taking a photograph or video of the celebrity signing the particular collectable item (having a unique identifier) and distributing memorablia kit that includes both the original signed collectable and a storage medium with the image.

The applicant’s non-analogous argument here is simply that DeFabio uses a different method of authentication. That approach, however, would prove too much, since all obvousness-type art exhibit some differences from the invention at issue. Macor’s line would effectively exclude all obviousness-type prior art and entirely undermine the doctrine. In patent law class, I like to discuss the idea of eliminating the obviousness doctrine as a hypothetical what-if scenario. But, the Supreme Court will certainly not be the body that takes that transformational step. The Federal Circuit decided this case without opinion and I expect the Supreme Court to follow that approach as well.

anon, it is a bit late now, to get this thread going again. But on the subject of “non-analogous” prior art, I reproduce below the prior art summarizing text from the Court of Appeal in the Great Atlantic supermarket open-fronted reciprocatory frame case. I do this because Random Guy, earlier in this thread, thinks SCOTUS was right to find the claim obvious and I disagree with him on that.

It would indeed be interesting to have comments from others, on the issue whether lift-off enclosed wall, triangular pool ball frames are “analogous” to an open-fronted, rectangular and reciprocatory supermarket check-out frame. Here the text:

“Seventeen patents which had not been cited by the Patent Office during the prosecution of the Turnham application were introduced as evidence of anticipation of the Turnham device. It is not necessary to discuss these in detail. For the most part they are in totally nonanalogous art. Marois, 1,654,692, is a flat slab movable back and forth under a screen protecting a cashier’s window. Varnum, 1,725,494, and Dickinson, 1,115,911, are patents for pool ball racks. The racks in question are closed and are not self-unloading, as is the U-shaped rack. Neither Arnold, 1,708,407, Rorrer, 1,873,852, nor Greenberg, 1,384,191, has the bottomless rack. Anderson, 1,788,759, is an ordinary belt type of conveyor. As shown in this record, no patent in the prior art attacked the bottleneck presented at the checkout counter in the self-serve store. Appellant concedes that no prior use of the bottomless rack in such a combination is shown. We conclude that substantial evidence supports the findings of the District Court that novelty and invention exist.”

“Seventeen patents… were introduced as evidence of anticipation of the Turnham device… For the most part they are in totally nonanalogous art”

First thought is that “analogous art” is meaningless in an anticipation context.

If you want to focus on obviousness, then focus on obviousness.

…if though, you already know that “analogous” is not a factor for anticipation, and you are merely providing that quote as an indicator that our Supteme Court was off, then I say: point well made.

Did the Supreme Court get it right here; no. Random and I indeed disagree on that.

Did the court of appeal see it right; yes. Was the Supreme Court subjective; yes. Was the court of appeal objective; yes.

The PHOSITA seeking to improve throughput at a supermarket check-out, and diligently researching the entire prior art universe for hints or suggestions how to do it, would not have come to the idea of the Turnham reciprocatory rectangular open-fronted top-less, base-less frame as claimed. And that would have been so, even if that notional person had played pool every evening, at the start of every game using (as one does) the ubiquitous closed triangular lift-off frame to set up the balls on the green baize. Why? Because, one doesn’t reciprocate the frame. Rather, one lifts it off the table. The frame is not for translating successive batches of balls over the green baize from A to B, by cyclic reciprocatory sliding movements, forward to B each time full, and back again empty to starting point A. It lacks Turnham’s guide rails and handle. Of course it does. It makes no sense to include such feature on a triangular pool ball racking frame. To say that the pool ball frame is the same as Turnham because both are “3-sided” is, in my opinion, a poor basis to dismiss the claimed check-out as obvious.

…and yet, you actively sought ‘to be in agreement’ (at least as far your niceties go) with a person has flat out stated the opposite position…

More than once.

In this thread.

On this very topic.

Why?

Why? Because of my conviction, that Patent Office examiners are intelligent and conscientious and well-meaning, so will agree with me as soon as they and I are “on the same page”. It is my experience that when they disagree with me it is because, up to that point, I have failed to explain myself clearly enough.

See, here, Random has given up arguing with me. I can guess why.

And yet I saw through you immediately and pointed such out, noting as well that the points that Random puts forth, he has put forth before and that points counter to his view have also been put forth before.

Your “niceties” and fawning have done nothing to move towards resolution and — as I posted — merely obscure the differences; differences that yet remain.

Random’s “I don’t think we’re secretly agreeing here,” is most assured to be lost in the lack of interest brought about by the mewling “interrogating” style of MaxDrei desperately trying to remain in some odd type of good graces of “we really believe the same thing”….

You two simply do not. That you appear to WANT to do so, is simply rather odd. That you so eagerly sacrifice any type of meaning OR resolution (or even defining the boundaries between your opposing positions) BECAUSE of this odd insistence on politeness makes my point for me.

Thank you.

Seems that this thread has gone to sleep now, anon. I just wrote a new comment, but it failed to materialize. A pity.

Like many things here, actual resolution (and engaging in a substantive manner – especially at points of disagreement) apparently will not be realized.

Say: “Le vee.”

… and my point is proven yet again with the most recent exchanges by MaxDrei and Random…

“Motivation” as used to describe the (innate) value of a feature or of a secondary reference AND

“Motivation to combine” are two distinct and separate categories.

How often do practitioners see examiners treat the “value” of the mere existence of a secondary reference — in and OF itself — as a de facto combination reasoning?

How often does an examiner’s response sound in “well, it is always obvious to add a good thing to anything”…?

At 3111111, Random Guy asks:

“Can you point to a single KSR rationale of obviousness (with the possible exception of obvious to try) that would not be a teaching, suggestion or motivation if it wasn’t written down beforehand?”

and I am having difficulty understanding his point. Am I to understand that the TSM lives on, undisturbed by KSR?

My problem is that, with the benefit of hindsight, it is too easy (at least in non-chemical fields) to be seduced by one’s subjective opinion that, surely, what is being claimed would have been obvious to the PHOSITA. The need to find a motivation to combine, actually within the prior art universe as it existed prior to the date of the claim is, for me, the necessary brake on hindsight subjectivity of the obviousness assessment.

Where in KSR is there any such brake?

Am I to understand that the TSM lives on, undisturbed by KSR?

Justice Kennedy’s KSR opinion pulled the same move with TSM that his Bilski opinion pulled with MoT—i.e., he changed TSM from being the test for obviousness into merely a “useful clue” of obviousness.

What does “useful clue” mean? Who knows? Justice Kennedy does not say (because he could not tell you if he tried).

I think that the cash value of all this is that if your claim fails TSM, then it is obvious (as it should be). If, however, your claim passes TSM, this is no longer good enough to establish that the claim is not obvious.

Greg,

Several of us await your cognitive defense of your larger positions as stated on this thread.

Who knows? The law clerk who Justice Kennedy’s “opinion” does not say (because he could not tell you if he tried).

Fixed it for you.

Who wrote Justice Kennedy’s “opinion”

Seems to me that it works either way. Neither Justice Kennedy nor the clerk who wrote the opinion could tell you what “useful clue” means. Come to that, I doubt that any of the other 8 justices who signed on to the unanimous KSR opinion could explain what is meant by “useful clue” in the context of either KSR or Bilski.

Sorry, I my memory, KSR used exactly the same words (“useful clue”) as Bilski, but in reality the KSR said “helpful insight.” Six of one, half dozen of another…

Well, one thing is clear as to what EITHER phrase does not mean:

A hard and fast rule of law (or legal requirement – six of one and all that )

)

My problem is that, with the benefit of hindsight, it is too easy (at least in non-chemical fields) to be seduced by one’s subjective opinion that, surely, what is being claimed would have been obvious to the PHOSITA. The need to find a motivation to combine, actually within the prior art universe as it existed prior to the date of the claim is, for me, the necessary brake on hindsight subjectivity of the obviousness assessment.

Again, for your practioners, unless someone is citing to MPEP 2143, every “motivation to combine” you’re getting is, in fact, either a strong TSM (by citation to text) or a weak TSM which you may or may not challenge. But a TSM is an *option* for showing obviousess. The vast majority of weak TSMs that are cited are in fact swallowed by much broader objective KSR rationales, the most common of which is simple combination.

Here let’s take a hypothetical:

I claim a system comprising a toaster and a car.

A “Strong” TSM person would command one to find a textual statement suggesting the toaster be put into the car. They’re not going to find one, because all the toaster references are concerned with making a better toaster. The toaster/car combination lacks (and here’s the money word) synergy. The car does not move faster when it has a toaster in it, nor does a toaster make toast better. Because a toaster can be used anywhere there is sufficient electricity to power it, nobody is going to list off everywhere a toaster can be placed. Consequently, nobody suggests placing a toaster in a car, and there is no teaching or motivation for a car *in particular* as the place to house a toaster.

Strong TSM people find *every non-synergistic combination* to be non-obvious. That turns the purpose of the patent act on its head – rather than only providing patents for what advances the art, the most patentable things are in fact combinations of known things that don’t advance anything. “There’s no particular reason to put an old toaster and a car together, so a claim combining them must be non-obvious.”

A “Weak” TSM person is actually the kind of person that you’re complaining about. These people do not cite to a textual motivation, but they reason a motivation based on a similarity of utility. So even though nobody told me to put a toaster in a car, I know that a toaster makes toast. It makes toast *everywhere* and you know what is a sub-set of the set of everywhere? That’s right – the inside of a car. So let’s take the general utility and apply it to the specific situation: “I find that one of ordinary skill would have been motivated to combine the toaster with the car so that they could eat toast while driving.” And this riles people up based upon how “reasonable” the adaption of general to specific utility is – toast while driving, ehh I’m not sure on that one. This one may be borderline nonobvious.

“Weak” TSM existed before KSR. Whenever a textual motivation could be found for combining a first device with a second device, there was a question as to whether it carried over to a similar third device. For example, suppose there is an actual invention for a heated beverage holder in a car. This heated holder *teaches* that heat be used in a car for food/drink purposes, and it *motivates* one to try and put hot things inside a car, but it certainly doesn’t speak directly to a toaster/car combination does it? What about a claim to a particular type of toaster – ToasterAlpha? Is the ToasterAlpha/Car combination suggested by a ToasterBeta/Car combination? What about ParticularToaster, is it motivated by GenericToaster? How far to extend the text is a subjective question.

All KSR did, with respect to TSM, is peel off the rest of the bandaid – It said you don’t need a textual reference at all, and its reasoning was pretty compelling given the outcomes of all the cases where TSM had screwed up.

Regardless, A KSR person is vastly more objective than the weak TSM person or even the strong TSM person, because the KSR person does not rely upon whether some combination happened to be written down or applies contrived logic as to how a person might think. A KSR person knows that a toaster preexisted the invention, and a car preexisted the invention, and then they look in the instant specification and find out that yup, a toaster in a car still provides both toast and locomotion. Then they state that a combination that only provides expected results is obvious under A&P Tea Co and MPEP 2143(I)(A). There’s no subjectiveness about it. There’s no question about whether a textual motivation for putting Toaster A in a car when the claim claims specific Toaster B counts. There’s no question about whether a car with a hot plate motivates a car with a toaster. There’s no question about what a human inventor’s line of thinking would be. There’s just the flat objective questions of 1) did the art know of this and 2) do they do what is expected?

People who argue that KSR is subjective are focusing only on the ability to use a non-textual motivation as a rationale* for obviousness. TSM (whether express or implied) is an *option* for a rationale of obviousness. What is necessary is a rationale, underpinned by evidence, as to why claimed subject matter is obvious. For virtually every “weak” TSM that has been conjured, one could apply an equally-valid and more objective rationale.

The logic shouldn’t be too hard to follow either – People generally do not view patent applications as the time to stretch their expressive writing legs. Virtually everything written in a patent application is written for a reason. When a patent pub is cited as a reference, the element that it is being cited for was put in there *for a reason*. It accomplishes a purpose. It likely accomplishes the exact same purpose that a claim under examination is using it for, because rarely do people actually find new uses for things (which is a nice way of saying that very few of people who end up getting patents are in fact true inventors). Consequently, when an examiner cites Ref A and Ref B and conjures some (usually true but factually unsupported on the record) reason to combine A and B, they’re taking the weak tsm option of showing obviousness when they could just as easily use simple combination or substitution.

The relevant holding of KSR is the assertion that application of largely undeniable logic (e.g. When people know that A and B are substitutes, they might try using B in place of A when told to use A; which is neither shocking nor was it even legally novel when KSR came around) is sufficient to show obviousness. The fact that KSR allowed for a non-textual TSM is largely beside the point, because one is simply not required to think like a person of skill and ask what might motivate them. The fact that one might be motivated to do something is a good rational reason as to why they might engage in conduct and render the end-result of that conduct obvious, but it’s hardly the most wide-ranging basis for obviousness.

I have to say how thankful I am to you, Random, for that riff on American TSM. In particular how it is used by some to turn the purpose of the Patent Act on its head. As you say, what is needed is:

“a rationale, underpinned by evidence, as to why claimed subject matter is obvious.”

You cite the Atlantic case from the 1950’s for the notion that a combination that delivers only results that are “expected” is indeed obvious. For my part, I have a problem with that. It is unhelpful, superficial and simplistic, tainted with hindsight, subjective and so will often deliver the “wrong” result.

The Atlantic invention is something I saw in supermarkets in England in my childhood, and thought how clever it was. And the case dwells on the secondary indicator of commercial success. It was a good invention, needed, copied, and genuinely deserving of patent protection. But it was mechanically very simple indeed. anybody could have devised it, even a Supreme Court judge.

I read SCOTUS in Atlantic and cringe. Frankly, I think it is a mile short on a convincing “rationale” for its obviousness finding. Frankly, it is poor treatment of a deserving inventor, who had brought real progress to the checkout arts, to dismiss the new and useful device claimed, just because each one of its features (no top, no base, a pair of side walls, back wall, handle, a pair of runners) are all features known, as such, in the state of the art.

We differ on what is a “combination” and what is a mere “aggregation” (or what the English courts might call a “collocation”). Your “toaster + car” is, for me, no combination. But Atlantic’s new generation supermarket checkout shuttle carriage was.

All of this leaves me thinking that EPO-style TSM is fit for the purpose of answering accurately the question “Obvious Y/N” whereas USA-form TSM is not.

It is only Random’s version that is not,

Random’s version is simply not correct, as his version leads only to a two-path system:

Flash of Genius, or

Pure serendipity.

This has been explicated previously many times now.

It is unhelpful, superficial and simplistic, tainted with hindsight, subjective and so will often deliver the “wrong” result.

It depends on what your goal is. If your goal is to ensure that a patent is only awarded for an advancement, then retelling people what they already knew is not patentable. Consequently, doing only what is expected is only telling the art what it already knew, and does not advance the art.

The Atlantic invention is something I saw in supermarkets in England in my childhood, and thought how clever it was. And the case dwells on the secondary indicator of commercial success. It was a good invention, needed, copied, and genuinely deserving of patent protection. But it was mechanically very simple indeed. anybody could have devised it, even a Supreme Court judge.

It sounds like you were impressed by the magnitude of the leap in efficiency that one invention had over a market-share prior art. The magnitude of utility doesn’t make an obvious invention less obvious, nor does the comparison to other ubiquitous commercializations.

Saying it was mechanically very simple indeed is the only relevant patent concern. The rest of the commentary is relevant only to commercialization, not invention.

I read SCOTUS in Atlantic and cringe. Frankly, I think it is a mile short on a convincing “rationale” for its obviousness finding. Frankly, it is poor treatment of a deserving inventor, who had brought real progress to the checkout arts, to dismiss the new and useful device claimed, just because each one of its features (no top, no base, a pair of side walls, back wall, handle, a pair of runners) are all features known, as such, in the state of the art.

Why so mad at SCOTUS? They were simply taking the facts that the district court had found:

The District Court found.

“15. Claims 4, 5 and 6 of the patent in suit define a new combination of elements brought together for the first time by Turnham to provide an improved check-out counter.

“16. Three-sided bottomless racks or trays had been used in racking pool balls prior to the Turnham invention. Also checking-out counters were known. Moreover, guide rails for trays had been used in self-serve restaurants.

“However, the conception of a counter with an extension to receive a bottomless self-unloading tray with which to push the contents of the tray in front of the cashier was a decidedly novel feature and constitutes a new and useful combination.”

“17. There is no similarity between the prior art patents cited by the Patent Office or the defendant and the invention disclosed in the Turnham patent.”

“18. No evidence was introduced establishing that anyone prior to Turnham used a three-sided bottomless tray in combination with a checking-out counter.”

The district court, much like yourself, wrote extensively about the utility and commercial success of the combination. The federal circuit made much of the long-felt need, while admitting that “One could be blinded in this case by the simplicity of the device,” which you also pointed out. The conclusion seems rather mundane.

Nobody suggested he actually advanced anything. It seems like he took a number of things which were all known to work, and put them together to work in the manner expected. What he did, rather than invent, was apply other people’s inventions in their usual manner for commercial success. Well I do that every day, but that doesn’t make me an inventor either.

As an initial point, I very much doubt you could have a real patent system where the validity of the patent relies upon how much commercial success it generates, or upon the magnitude of the advancement. Beyond that, how can you hope to run a system where combining things for their known results is inventive? You distinguish (and I do like your combination/aggregation language, we used to use such and no longer do, I wish we did) between combination and aggregation, but you articulate no dividing line between them. Why is it my toaster and car, which are doing exactly what you’d expect, are unpatentable aggregations while this guy’s rail and bottomless tray is a patentable combination? Because it succeeded more? By that standard you’d never have invention in unpopular fields. Because it was so much more useful than prior supermarket counters? Clearly you have not experienced the important difference between warmly popped piece of toast and a cold, stale piece brought into the car from a cold winters morn, my friend. You started off this conversation complaining of subjectiveness, and yet I provide an objective standard and you’re sitting here telling me you know it when you see it.

OK. Here the Atlantic case, done the EPO way.

Field: supermarket check-out tech.

Problem: how to get more throughput, per check-out. (This was before the days of conveyor belts, IR scanners and bar codes.)

Solution: install on the counter a reciprocatory slider on rails, with a handle for the check-out operative. Slider has back wall but no front wall. It has side walls but no top cover and no base plate.

Prior art: Check-out counters. In pool halls, Turnham’s equilateral triangular topless baseless lift-off frame to receive pool balls for setting them up, on the green baize, prior to tee-ing off the game.

Hint or suggestion? No. The triangular frame is useless for speeding check-out throughput. Not only don’t you reciprocate the triangle. You can’t even start to reciprocate it to unload it, because its three walls fully enclose the space within. It has no handle. Why should it?

Any person asked by a supermarket tech firm to search for ways to speed up the check-out would not find the triangle and even if they did they would not be motivated by the triangle to use it as a solution to the problem – even if that person were somebody who regularly plays pool hours each day.

I ask you: how disingenuous was it of the court, to write off the claim because Turnham is also “3-sided”?

Now to your in-car toaster.

Field: in-car food

Problem: toast eaters in cars still want toast fresh, and fresh is only straight out of the toaster.

Solution: in-car toaster.

Hint or suggestion: As soon as you state the problem you reveal the solution.

Can you see the difference now? Oh and BTW, I fully agree with you that we must clearly distinguish between novelty and obviousness, between technical obviousness and commercial obviousness, and between what is subjective and what is objectively derivable from the prior art universe.

Sorry. I see now. “Turnham” is the 3-sided tray of the claim, not the triangular prior art pool ball frame. But never mind. The point stands.

As to Anderson, of course it is obvious (also at the EPO) to mount two machines, previously each on its own chassis, on one common chassis. Just as obvious as mounting a toaster in a car. There is a very old case in England on that point, often referred to as the sausage machine case. Williams v. Nye, 1890.

link to ipkitten.blogspot.com

Hint or suggestion? No. The triangular frame is useless for speeding check-out throughput. Not only don’t you reciprocate the triangle. You can’t even start to reciprocate it to unload it, because its three walls fully enclose the space within. It has no handle. Why should it?

The question is not whether the invention is the most obvious invention. The question is whether the invention is obvious. Something is obvious when the mechanism requires nothing more than already-known knowledge.

If I am in a building I can throw a chair through a window to break it and escape. The fact that the most obvious solution is to use an unlocked door does not change the fact that I understand the fragility of the window and the heft of the chair.

I am hampered in our particular discussion with the checkout counter as I have never seen the device, but it sounds to me like it is simply a non-triangular pool rack on guide rails which receives a hand-held shopping carrier. I do not need to be told that other things will glide inside the pool rack beyond billiard balls, and I do not need to be told that guide rails will keep something inbetween them. It may not be the most obvious invention, but it is obvious because it requires no additional knowledge from me.

Regardless, the question is not what I think, as I have no particular knowledge. All I need to know is that the district court found the structures were previously known for performing the same function. If there was an error in the fact-finding there is a systemic solution for that. Given that those facts have been found, all I need to do is come to the conclusion that someone would have posited that things other than billiard balls could be moved. I easily come to such a conclusion, and therefore using it for groceries is obvious, as it would be for sliding any other thing capable of being slid.

To put it in a generic (if less accurate context) – the knowledge of a machine to perform a function always suggests the use of that structure for performing that function and similar functions. If you have a lock in front of you and someone hands you a key, you don’t need to be told to try to use the key to unlock the door. Similarly, if I want to slide something from one location to another, and I know of structures that allow for controlled sliding, application of those structures is obvious even without someone telling me. The fact that sliding may not be the most obvious solution or that if I was going to slide I had a plethora of structures and no particular reason to pick any particular structure I could use doesn’t change the fact that the solution *is* obvious because it only relies upon knowledge I already had.

Ah! So now we have it. A different appreciation of how Turnham works. Thank you, Random.

In my youth I bought goods at supermarkets. One day, I encountered the Turnham frame and found that check-out queues were markedly shorter. Why? Because customer and check-out operative are working simultaneously. Consider:

While the customer in front of me is paying, I am unloading selected items out of my trolley and into the frame that is at rest in its starting position, on an extended counter, between rails. Next, check-out operator pulls the frame to the till and then immediately pushes it back to me, in a single quick reciprocatory movement. I then load a second tranche of goods into the frame while my first tranche is being put through the till. Next: the tray shuttles forward and back a second time, and even while I am putting a third batch of goods into the frame my second batch is being cashed up.

My trolley is now empty. My goods are cashed up. I step forward one pace, pay, put my paid for and already bagged up goods back into the empty trolley (or whatever) and proceed to the car park.

You can go on all you like about the function of a pool racking frame being for “sliding”. I still don’t buy your “no change of function” line.

I remain convinced that EPO-PSA (TSM, EPO style) filters fairly for obviousness, but ONLY when it is correctly executed, correctly defining the “objective technical problem” .

Very many people think they understand EPO-PSA. Very few do, because very few take the trouble to get themselves properly educated how to implement it.

In Great Atlantic, the appeal court was not far off an EPO-PSA approach. Good for them. In other cases, aggregations, collocations, Anderson for example, you, me, the CAFC and the EPO are all agreed: plainly obvious.

Thanks for playing.

One day, I encountered the Turnham frame and found that check-out queues were markedly shorter. Why? Because customer and check-out operative are working simultaneously.

Is the claim to a method of parallel processing of groceries, or is the claim to a mechanical structure?

You can go on all you like about the function of a pool racking frame being for “sliding”. I still don’t buy your “no change of function” line.

I suppose by your logic using a conveyor belt to load your luggage onto a plane and using a conveyor belt to bring your groceries to the grocer are separate, non-obvious inventions. Certainly the existence of airplane loading is no more suggestive to supermarket work than billiard racking is. I mean, that’s certainly a way to do it, but I doubt the poor conveyor belt inventor is happy that other, richer people are reading his patent and invading his monopoly by simply re-applying it to get other things moved.

“Certainly the existence of airplane loading is no more suggestive to supermarket work than billiard racking is.”

Wow, Random, you are really reaching now – no wonder that you have been smacked down….

Random, I see now your answer of Feb 27. Thanks for that: because it reveals to me the gulf that separates how obviousness objections are formulated at the EPO and at the USPTO. The EPO takes an “effects-based” approach to obviousness, based on PCT Rule 5, from 1973. You not, it seems.

We each think we are less subjective and more objective than the other, less afflicted by impermissible ex post facto reasoning, less tainted by impermissible hindsight. I should welcome comment from those who draft for both the USPTO and the EPO, those who prosecute before both Offices. Let them give their assessments, I say.

MaxDrei,

PLEASE STOP equating the nonsense from Random as how the US Sovereign actually treats the legal notion of obviousness.

…but more (directly) to your point of PCT Rule 5, thank you for that – and it is immediately to be pointed out that US applications will not — as a general rule due directly to the concept of Patent Profanity — engage in the description writing that so heavily is linked to the prior art.

e.g., link to wipo.int

5.1(a)(ii), (iii), and quite in fact 5.1(b) is the “universal” out that US prosecution will follow.

One may place a fair amount of blame on our courts who have used any such “straightforwardness” that otherwise would be “helpful” as platforms for denying patent protection here.

Per Random’s “logic,” ANY and ALL engineering is purely obvious, and for Random, patents devolve into two distinct categories: Flash of Genius and Pure Serindipity.

This is a point previously put on the table that Random has refused to engage in.

The current exchange changes nothing for Random’s misapprehension of the Law.

I think that the cash value of all this is that if your claim fails TSM, then it is obvious (as it should be). If, however, your claim passes TSM, this is no longer good enough to establish that the claim is not obvious.

There’s no “I think” here. What is required is a rationale, that is underpinned by evidence, as to why the hypothetical person of skill would find the claimed subject matter obvious. A TSM is one option for meeting that rationale. There are other options. They’re (theoretically) non-exhaustive, but in practice are all spelled out in MPEP 2143.

You clearly still haven’t read your Anderson’s Blackrock, and there’s some new names here. So I’ll remind the class:

Just to reiterate the important facts of that case, they were –

1) The art knew of paving machines

2) The art knew of radiant heaters, including the same radiant heater claimed

3) Radiant heaters were used to fuse cold, previously laid concrete with hot, newly laid concrete. If no heat was used the two slabs would not mesh together. If open flame was used it would make the situation worse. Radiant heaters could fuse the slabs together. Thus radiant heaters had a known use for a known effect.

4) Since the invention of the radiant heater the art turned away from radiant heat, and instead cut back the cold slab and laid a small hot area to fuse the cold and hot slabs together, deciding that was the better method of action. Many prosecutors today would incorrectly call this a “teaching away.”

5) There was no motivation to use radiant heat given the state of the art, in fact, two people testified they didn’t think it would work

6) The claim was for a paving machine that hung a radiant heater on it

7) Applying the radiant heater acted just as the old patent suggested it would to achieve the results expected

The federal circuit threw a bevy of secondary considerations at the patent – there was a long felt need, others in the art were skeptical, it enjoyed commercial success, it was copied, and the copying company specifically advertised the combination.

I have no better summary of the strength of the fed cir’s view of non-obviousness than to just quote a paragraph from the federal circuit here, a quote that manifests how many people on this board think:

As we have indicated, it is not contended that Neville’s claims are anticipated by any prior art patent. It is contended that three or more of them, together, disclose all that Neville claimed, and that because he cannot separately claim the generator or the basic paving machine, he cannot claim the combination. The defense is simply obviousness. The prior art, however, is predominantly a long history of failure to solve the problem by heat treatment. At a time when the industry was concentrating on a quite different, though expensive, partial corrective, there was nothing in the junk pile of prior art heat treatment patents to make it obvious to anyone that they supplied the ultimate solution. That this is so is forcefully demonstrated by the duration of the fruitless search, by the skepticism and incredulity with which experts in the field received Neville’s disclosure, by its commercial success after demonstrations dissipated the disbelief of the experts, by the conduct of competitors in accepting licenses and purchasing equipment and the bold tribute of the alleged infringer in hailing it as the very antithesis of the obvious.

A masterful summary of why a human inventor, sitting in the field, would not be motivated to combine things to generate the claimed invention. Ergo, the federal circuit thought, the invention was nonobvious.

The federal circuit was reversed.

They were reversed because “three or more [references], together, disclose all that [was] claimed, and that because [one] cannot separately claim the generator the basic paving machine, [one] cannot claim the combination.” The claims were for three known things, placed into combination with each other, that had already been patented and were dedicated to the public. When they were brought into orbit of each other, they performed no differently than if they were alone. To a hypothetical person that knows all the art, they were obvious – as obvious as one’s ability to open three separate doors using three known keys despite having multiple keys on one’s keyring that might distract one’s tiny mind with their shinyness.

Andersons Blackrock is a 1969 case.

To a person who has all the knowledge in the art, a known thing may be used for its known purpose, and that use is obvious. It does not matter if the current trend is moving in another direction. It does not matter if a *human* of ordinary skill does not come up with the combination, or even an entire field of humans, such that there is a long felt need. The questions are simply “was it known” and “does it work as expected.” That renders it obvious.

The problem with “weak” TSM people is that they would be swayed by that Anderson’s paragraph – that because nobody had suggested the combination, and because there was no motivation to apply the combination, the combination was non-obvious. (A Strong TSM person would at least have the courage to make the claim non-obvious regardless of what people said about the inventor or how the invention was received.)

This allows for the repatenting of old things, because it does not focus on the only valid goal of patent law – to promote the progress. For a patent to be valid it must tell the art something it did not previously know. Generally, in combinations of known things, that means that there must be some sort of synergistic or unexpected result. If A causes X and B causes Y, a claim to AB is obvious when XY results and non-obvious when Z results, and that is true regardless of any motivation to combine AB.

My problem is that, with the benefit of hindsight, it is too easy (at least in non-chemical fields) to be seduced by one’s subjective opinion that, surely, what is being claimed would have been obvious to the PHOSITA.

There is generally nothing subjective about it. There is nothing “hindsight” about the Anderson Blackrock conclusion, because the question does not focus on whether a human would have made a particular combination out of a vast field of options, or whether that same human would have gone down a different path because of potentially more lucrative outcomes. The question isn’t “What is the *most* obvious invention based on all these references?” The question is simply “Is this invention obvious to someone who knows everything in the art?” Combinations are generally obvious because their pieces are generally known and they generally do not perform differently in concert than they do separately.

Nonobviousness can largely be answered in the negative – if you provide a claim and you cannot articulate what was taught to the art beyond what is in cited references, that claim is likely obvious under KSR. That’s a significantly objective test.

The standard only *appears* to be subjective because people do not understand the breadth of the power of the PHOSITA and what its function is. I agree that it certainly may *seem* to be subjective if you mistakenly ask the questions *what would a limited person do* and *why* instead of asking the question of what is obviously possible to one who has all the knowledge in the art and an ordinary amount of creativity and skill. When one has a toolbox that is hundreds of thousands of disclosures deep, one has a lot of obvious options for achieving the results that one may want to achieve in any given position. If you start asking how a human would problem-solve as opposed to “The art knows 500 ways of doing this, is this one of them?” you might start thinking that Neville was an inventor or (in the case of strong TSM people) that virtually everyone going to the store is an inventor because nobody micromanages their daily lives in writing.

Consequently, people keep getting caught up in meaningless subjective questions (trying to answer “Why?”s and bickering over the reasonableness of the answer) when KSR allows for objective if-thens. The vast majority of the time one can pinpoint the alleged inventive aspect of a claim and reduce the question of obviousness to “If the art already knew that A caused X, this claim will end up being obvious, and if not, this claim will be non-obvious.” Then its a simple matter of finding out if the A-X linkage was known.

It is true that something is not obvious *merely* because all the pieces preexisted in the art, but that shouldn’t be taken to mean that the remaining steps are difficult ones. The vast majority of the time one *can* provide a reasoned rationale for combining all of the pieces in the art without resorting to a TSM, explicit or otherwise.

I agree that objectivity requires that we do obviousness through the prism of the PHOSITA:

“one who has all the knowledge in the art and an ordinary amount of creativity and skill. When one has a toolbox that is hundreds of thousands of disclosures deep, one has a lot of obvious options for achieving the results that one may want to achieve in any given position.”

All the more reason to be sceptical of declaring obvious (to a person who knows everything) each and every combination of features, each one of itself known to the PHOSITA and each delivering, as part of the claimed combination, only the result that would already have been “expected” by the PHOSITA from that feature. For that can be unfair to deserving inventors who really have promoted progress.

The fawning politeness gets in the way of the fact you that you disagree with Random here MaxDrei.

Not at all. My motivation in interrogating Random is to test the intellectual rigor of EPO-PSA by challenging him on USA-TSM and seeing how he answers. It is my perception that Random is a thinker who knows a lot and can communicate it with precision, and somebody without a vested interest in maximising the scope and number of issued patents. There I go again, eh, fawning all over him.

Perhaps Random has a better grasp of the facts in the Atlantic case than I do. Atlantic was decided in the 1950’s. Was that not during the period when the Courts in the USA needed only to see a patent to know that it was a Bad’un? What’s your “take” on Atlantic? After all, you suppose yourself to be the expert on big box of electrons type cases. Wrongly decided, I guess you would say.

There is NO “interrogating” in your reply, as it is obsequious to a fault.

I put it to you that he may not have even recognized that you disagreed with him, let alone as to WHY you disagreed with him.

“my perception that Random is a thinker who knows a lot and can communicate it with precision”

Your perception is seriously flawed, as the abundant weaknesses in Random’s position have long been made of note, and he has refused to even engage on those points. He is no more a “serious thinker” than you are (sorry if that hurts).

“somebody without a vested interest in maximising the scope and number of issued patents.”

This conclusion/feeling of yours is NOWHERE evident. So yes, you are fawning again.

“After all, you suppose yourself to be the expert on big box of electrons type cases”

Wow, do you miss the point of that put-down…

Let’s NOT switch this to me just yet. Let’s see if you can be more clear and direct in your disagreement first.

to be more clear as to your (clearly snide) comment about “maximizing the scope and number of issued patents,”…

You basically insert an empty ad hominem – AS IF the maximizing of scope and number of issued patents is somehow a B A D thing. Such is simply NOT a bad thing, and if you had any fricken c1ue as to why the maximization of scope and number of issue patents is fully in line with HAVING a patent system, then you would not have attempted such a distraction.

Note that your statement was NOT “somebody without a vested interest in maximising the scope and number of wrongly issued patents.” – and probably for obvious reasons, as that would have been a clear indicator that you were engaging in a dissembling manner with me.

Being offended in this conversation is definitely a choice. This is not a court hearing, so no one is obliged to articulate just how much they disagree with anyone. In the meanwhile, I am going to look into not getting notifications on this post because the majority of the comments are more dysfunctional than the Kardashians, and I resent even having to make that comparison.

For that can be unfair to deserving inventors who really have promoted progress.

Who is this? And what progress have they promoted? I mean this seriously. I can’t imagine any common situations where one will have told the art what it already knows, and yet be declared someone who advances something.

All the more reason to be sceptical of declaring obvious (to a person who knows everything) each and every combination of features, each one of itself known to the PHOSITA and each delivering, as part of the claimed combination, only the result that would already have been “expected” by the PHOSITA from that feature.

Why wouldn’t each combination be obvious? Let’s assume there is a three step process, the result of which is some beneficial effect. The art knows of 10 ways to perform the first step, 100 ways to perform the second, and 1000 ways to perform the third. It seems pretty clear that a person that has the sum total of the art knows of one million combinations that achieve the goal state. The hypothetical person can give you the exact structure of each one – [5], [93], [651] is one, while [5],[93],[652] is another. Further, the person knows (correctly) what will happen when each is applied – perhaps x, [51], x is more expensive but more accurate than x, [67], x, but the result is unsurprising.

The question is not whether combination 581,293 is the best overall combination, nor is the question whether that structure is way way better than the prevalent structure being used conventionally today. Nor is the question even “Would anyone pick 581,293 as opposed to any other number”? The question is simply if 581,293 can be generated without some non-obvious application of knowledge. To a person who has all the knowledge, selecting 581,293 to achieve the result is as easy as reaching into your pocket and selecting the key that will open the door in front of you. You wouldn’t suggest that that becomes inventive, even if you had a very large keyring, would you?

I wonder, Random, whether we are of the same mind but simply talking past one another. I hope so anyway.

Take the supermarket check-out sliding device of the Atlantic case that solved the problem how to speed up tallying of a trolley-load of goods by a single cashier at the check-out. It’s a bit like the rake that casino croupiers use to rake in to the bank all the chips on the table at the end of a game of roulette. Are you saying it deserved to be declared obvious because sliding rails are known, handles are known, pairs of side walls are known and back walls are known? For me, and for the EPO, a combination is something in which all recited elements work together to deliver a new result. All featues are necessary. Anything less and the new result is not delivered. Taken together, they are sufficient to deliver the new result.

This thinking, what it means to be a “combination”, is at the heart of the obviousness enquiry at the EPO. You haven’t yet shaken my confidence in it. As I say, I suspect that basically we do not disagree.

Have just seen your answer of yesterday evening, 9212. Many thanks.

Will mull it over and get back to you.

Are you saying it deserved to be declared obvious because sliding rails are known, handles are known, pairs of side walls are known and back walls are known?

That is not what the claim was for, but generally I agree with the concept that when sliding rails are used to keep something on a track, and handles are used to provide a grip surface, and back walls backstop something, then using them together is obvious. The “new result” is the natural result that would be expected from the combination.

There’s no benefit that warrants the monopoly. The person who applies the combination gains a commercial first mover advantage that rewards the use. But without a new mechanical disclosure there’s no art improvement that suggests we need a monopoly. The fact that commercial gain often motivates inventors does not mean commercial action is inventive action. They are simply two different things.

Don’t you see what a ridiculous hodgepodge the opposite rule would be? Take anderson’s blackrock. If the old radiant heater became patentable just because there was a pile of other art then it necessarily follows that any particular combination becomes non-obvious. There exist thousands of types of computer printers and thousands of types of computers. The fact that I nominate a particular printer and a particular laptop and claim them in a system when neither performs any differently than expected when put together simply means I am stealing other people’s inventions – someone else had the right to sell their inventive printer, and I’m cutting into the value of their patent by limiting their market for no legitimate art advancement benefit.

I don’t think we’re secretly agreeing here, because for me there is no distinction between printer/laptop and sliding guard rail/handle. You declare a “new result” for the latter, but the result of using the rail/handle is just as “new” as the printer/laptop is and it’s just as new as toaster/car would be. A car couldn’t make toast before the combination, nor could the laptop generate printed paper. How is that distinct from “Now people can slide their groceries”?

“Now people can slide their groceries” is too generous, as the claim doesn’t require that. What the claim requires a rail that slides things. Now people can slide things. At a minimum, railroads were ubiquitous. People knew you could create a rail system to slide things along it. Granted it was not hand pulled and did not (I’m not clear on this but this is my understanding) spring back when released? But those are 1) not claimed and 2) simple results of hand grips and weights.

Much like anderson’s blackrock, the application of known machinery is certainly a good commercial move, but that is what is supposed to happen when machinery passes to the public – general commercial usage for benefit. You don’t patent something, then re-patent it again every time it does something useful in a new context. You’d have some inventions that never pass to the public then.

No opportunity today, Random. Will get back to you tomorrow. Meanwhile, thanks for all those thoughts.

As typical, Random’s wants beg too much (aside from his odd use of “context,” for which, we would have to see a more “precise” meaning given):

“The application of known machinery is certainly a good commercial move, but that is what is supposed to happen when machinery passes to the public – general commercial usage for benefit. You don’t patent something, then re-patent it again every time it does something useful in a new context.”

Have Random discuss 35 100(b) — since he seems unable to provide any reasoning when others ask him about this.

Have Random discuss 35 100(b) — since he seems unable to provide any reasoning when others ask him about this.

It’s not a new use, its the same use. It’s sliding things. The fact that it slides strictly different things from before doesn’t render it non-obvious, because we already knew that multiple things slide. Each of the pieces of machinery that is combined does exactly what it does in every other context – the rails keep things on a line, the basket holds things within it, the handle allows for hand pulling.

This isn’t just me saying this, this is all of the district court, the appellate court and the supreme court (and, for that matter, MaxDrei as well). The only distinction between the supreme court’s reversal and the two lower court’s rules is that the lower courts viewed the extreme commercial success as sufficient in-and-of-itself to confer patentability – i.e. this thing was so widely adopted and so useful that if it was obvious it certainly would have been done before.

But A&P Tea, like all the other obviousness cases, holds that secondary indicia are just that – indicia for helping to solve close cases – not freestanding reasons for obviousness. It is not the case that every commercially successful thing is inherently patentable (just as it is not the case that commercial failure doesn’t render an otherwise non-obvious invention unpatentable). When you apply machinery for its known use, that is the public getting their quo for their previously-given quid. If you kept allowing re-patenting for simply re-stating what a known machine does, the re-patenter would be giving no quid, and the public (and the first patentee for that matter) would not be getting their quo.

anon likes to casually forget about that last sentence. It is as damaging if not more damaging to the patent system to tell an inventor “We’re going to publish your patent, and then other people can come along, cut-and-paste your language, and take away a customer’s use of your machine from your monopoly” as it would be to not give them a patent in the first place. Someone came up with, e.g., a guard rail, and they gave it to the public in exchange for a valuable monopoly. If you let someone else read the guard rail patent and regurgitate the guard rail disclosure, simply put into a particular context, and give them a patent for doing so, you harm the bargained-for monopoly by the guard rail inventor and destroy the incentive for inventive disclosure. Similarly, the public already paid for the guard rail disclosure. When you allow for a second patent for the same disclosure, you extend the exclusivity period beyond what the public bargained for. A patent simply cannot derive from nothing more than what was already shared with the public. Everyone who looks at the case agrees that the mechanism claimed is nothing more than adding known mechanisms together for their usual job. That ends the inquiry. The fact that it was extremely effective or commercially useful are benefits that derive to the original sub-part patentees or the public, not to someone else who just reads three patents and rewrites them in a single document.

Sorry Random, but you have to read the claim as a whole in order to be able to say “same use.”

Same type of use is just not the same as “same,” now is it?

“(and, for that matter, MaxDrei as well). ”

No. Actually MaxDrei is NOT agreeing with you on that point (even though he makes that more difficult to see for some odd reason).

“anon likes to casually forget about that last sentence.”

Not at all – your accusation has no merit, nor any support that anything that I have ever said would render your accusation to be accurate.

Quite in fact, “ and the public (and the first patentee for that matter) would not be getting their quo.” I have been the one that tells people that they have not followed the logic of this as pertains to a(n inadvertent) STRENGTHENING of patents.

That being said, I notice that you STILL HAVE NOT provided a view of 35 USC 100(b).

Now why is that?

Sorry Random, but you have to read the claim as a whole in order to be able to say “same use.”

That being said, I notice that you STILL HAVE NOT provided a view of 35 USC 100(b).

I won’t tilt at your horribly constructed windmill here. All 100b states is that a different use of a known structure constitutes a “process” for surpassing 101. It does not speak to whether it surpasses 103, because processes in general are still subject to 103 considerations. The fact that the art knew of rails that slid trays renders similarly structured rails that slide baskets or groceries obvious.

100b is not a sanction that different uses of known structures inherently overcome 103. Everything that is not anticipated at a minimum must operate differently in some fashion. If you read 100b to inherently render “different uses” patentable under 103 then 103 has no meaning at all.

Actually MaxDrei is NOT agreeing with you on that point (even though he makes that more difficult to see for some odd reason).

MaxDrei does agree with *the court* that the claimed mechanism is very simple and made up of things that existed before. MaxDrei simply also agrees with the district court and the CAFC that the secondary considerations render it nonobvious. His post at 9.2.1 could have been written by the appellate court.

It is telling that you won’t engage on the law and instead try to denigrate it as MY “horribly constructed windmill.”

I did not write that law — as you are fully aware of.

No, Random, what we have here is merely you unwilling to engage in a point of law that goes against your ardent affirmation bias.

As I have mentioned before, I pity those that have you as an Examiner, as you are unwilling to learn the actual law, and cling to your anti-patent notions.

Although the questions presented may be interesting in the abstract – the actual underlying arguments are extremely weak… The Federal Circuit decided this case without opinion and I expect the Supreme Court to follow that approach as well.

Thank heavens for that. The CAFC has been doing some interesting work lately in the non-analogous art doctrine (In re Natural Alternatives (2016), Smith & Nephew v. Hologic Inc (2018), etc). It would be a shame to see the SCotUS sweep away all of that good work. This is not the case that anyone should want to see the SCotUS take as a vehicle for elucidating the non-analogous art doctrine.

“This is not the case that anyone should want to see the SCotUS take as a vehicle for elucidating the non-analogous art doctrine.”

That may indeed be a good point, Greg.

And thanks for providing some tidbits of cases to check out.

(and so much for your past attempts to say that you cannot see my comments… )

)

Combining two items from comments to two different people (with a little change and emphasis added), and placing on top for some (hopefully) critical thoughts to be provoked:

1) A major problem with the use of “analogous” is that the term (and its counter-term) are not mutually exclusive. Two items (“objectively” in two different art units) may be considered analogous for certain features at the same time that for other features, the two items would be considered non-analogous.

2) Should any instance of restriction practice de facto implicate the required application of law during examination for obviousness for combinations of art items that are “objectively” classified under (merely) different art units?

For 2), how can ANY restriction practice that restricts along a (mere) “strict difference” classification find accord with what the Supreme Court wrote in KSR?

That is a good point anon. That is a good point anon. If a restriction is given shouldn’t that limit the art used for a rejection?

I’ve seen rejections that are just text matches from disparate art units cobbled together for a rejection. I’ve always been able to get around these where sometimes I’ve had to appeal. Frankly, in my practice, non-analogous art hasn’t been much of a problem in the last 5 years.

“If a restriction is given shouldn’t that limit the art used for a rejection?”

If an [administrative action] is given shouldn’t that limit the art used for a [substantive determination under the lawl]?

No bruh.

Pardon the Potential (re)Peat due to the Count Filter…

6 (and others),

It should be apparent from the context that I am not talking about ALL restrictions, and that certain restrictions are entirely appropriate.

No. As has been discussed prior, there are MANY restrictions that simply are not appropriate.

Random had used an example of something like a bed and a toaster.

I am talking more about a restriction received that was traversed, but maintained, between claim sets not only in the same class, but also in the same sub-class (as but one example of bad restriction practice).

Random also errs (and errs egregiously) in his attempt to not give credit to how I have described the fact that “analogous” is a feature-specific item, and that word and its counter-word simply are not mutually exclusive.

Lastly, several have jumped into the weeds and believe that I am advocating some type of “hard rules” that “must” follow from restriction practice when I am doing nothing of the sort, and instead, pointing out the realities of what naturally follows from some of the existing restriction practice by the Office that I have personally seen.

Come on people – THINK.

Don’t just see who the poster is and decide that you have to take an opposite stance.

“I am talking more about a restriction received that was traversed, but maintained, between claim sets not only in the same class, but also in the same sub-class (as but one example of bad restriction practice).”

I will presume that you mean that the sole justification for restriction was the diff classification and then you’re saying that they weren’t differently classified. If they’re species and it is a requirement to elect on for prosecution then that’s ok. But presuming it is a normal restriction between method/device/apparatus/etc. then ok, let’s just presume it is mistaken. Ok, so then it becomes:

“If an [INAPPROPRIATE administrative action] is given shouldn’t that limit the art used for a [substantive determination under the lawl]?”

The answer is still nah bruh.

“Lastly, several have jumped into the weeds and believe that I am advocating some type of “hard rules” that “must” follow from restriction practice when I am doing nothing of the sort, and instead, pointing out the realities of what naturally follows from some of the existing restriction practice by the Office that I have personally seen.

Come on people – THINK.”

You’re not expressing yourself sufficiently for anyone to understand how you’re drawing some substantive thing from an administrative procedural action, or else drawing a line from the one to the other.

““If an [INAPPROPRIATE administrative action] is given shouldn’t that limit the art used for a [substantive determination under the lawl]?”

The answer is still nah bruh. ”

Your paraphrase is still not accurate to what I am saying.

Again, I am not the one calling for some type of “hard rules” that “must” follow from restriction practice – instead, I am pointing out the realities of what naturally follows from some of the existing restriction practice by the Office that I have personally seen.

It is the EXAMINERS that when they restrict that they then de facto do not examine completely.

I am talking about examiners making a restriction requirement on the basis of “too many art units to search” when – PER KSR – the number of art units may have NO BEARING on the fact that multiply different art units may bear on the invention (think of Random’s feature emphasis of “mixing” for an invention of a concrete mixer…)

Let me put it to you another way, 6:

I want the most thorough and proper examination that my applicants paid their money for.

But if I am going to have to deal with improper restriction practice based solely on the whines of “too many art units” (some utter C R P of an “undue burden of searching”), you better believe that some pushback will be coming the examiner’s way.

As I had noted to Malcolm (but wiped out because Malcolm’s blight was (again) expunged: this is more to do with blatantly improper restriction practice that cannot possibly stand in accord with KSR.

“It is the EXAMINERS that when they restrict that they then de facto do not examine completely.”

O lol, if that is all you’re talking about then meh, that’s their call where to search. Not urs bruh. And they determine whether it was complete or not, not you. Though obviously in reality some searches definitely will have missed their mark/sub-group, I don’t see what you’re bringing up about this situation re 103.

“PER KSR – the number of art units may have NO BEARING on the fact that multiply different art units may bear on the invention”

First of all it is “sub-groups” not “art units”. Second of all, yes, that’s all true, but there is no conflict there. The office is making a procedural/administrative determination of where best to use its search $ when planning the search. The office is not generally determining the scope of everywhere art could possibly be. Capiche?

“But if I am going to have to deal with improper restriction practice based solely on the whines of “too many art units” (some utter C R P of an “undue burden of searching”), you better believe that some pushback will be coming the examiner’s way.”

Mmmm, yeah that undue burden of searching is a justified administrative concern, and is also a proper justification for restriction, by itself. If it is too much subject matter for searching in one chunk for right then, then you have to obey the procedure of filing a DIV. Restrictions are supposed to be all procedure bruh.

“But if I am going to have to deal with improper restriction practice based solely on the whines of “too many art units” (some utter C R P of an “undue burden of searching”), you better believe that some pushback will be coming the examiner’s way.

As I had noted to Malcolm (but wiped out because Malcolm’s blight was (again) expunged: this is more to do with blatantly improper restriction practice that cannot possibly stand in accord with KSR.”

So this is just you trying to dream up an argument against restrictions that you think are wrong? Wow. What a waste of my time. Learn2arguerestrictions bruh. And re KSR, KSR itself, and all other obviousness law in existence, has squat to do with the administrative concerns and procedure that are what restrictions are all about save to the extent that the office wrote them into their own guidelines for examiners (things the examiner can foresee as being obvious variants/species shouldn’t be restricted). If you think the examiner is wrong about something in the restriction then have your say.

6,

You are off track yet again, and worse, you are slipping into your old “blame the applicant” mode.

You are just not paying attention to what I have already stated.

Mmmm, yeah that undue burden of searching is a justified administrative concern, and is also a proper justification for restriction, by itself.

lol. I see that contempt for the actual law is alive and well in the examining corps.

I see that contempt for the actual law is alive and well in the examining corps.

I bow to no one in my frustration and dismay with the way that restriction is used in practice (at least in the 1600s, which is the only end of the PTO that I know well from actual experience). I do, however, have to wonder what “actual law” you have in mind?

Neither the statutes nor the cases give much of a standard as to when restriction is or is not appropriate. How do we conclude that the examiner corps are ignoring “actual law”?

“lol. I see that contempt for the actual law is alive and well in the examining corps.”

Dan expresses his re tarda tion.

Nobody has herp contempt for da lawl. The lawl is literally what is being used here tard.

“You are off track yet again, and worse, you are slipping into your old “blame the applicant” mode.”

If I’m off track discussing the subject you want to discuss that’s your bad re re. You’ve got to express what you want to discuss in a manner other people can understand or it cannot be discussed.

“You are just not paying attention to what I have already stated.”

I fucing read and understood all your blabbering re re. If you still haven’t managed to get your point across learn to express yourself better.

Well that was some pruning.

Thanks Malcolm, you added to your most ever – more than all others combined expungements; but this time taking some substantive comments along with your (removed) blight

In general, for reversing the PTAB to win a 103 argument on appeal at the Fed. Cir., appellate experts have noted for many years that you should make expert supporting declarations of record, even if that requires a continuation or RCE to do so before appealing.

Also, a “non-analogous” art argument needs a valid definition of WHO the 103 POSITA is for that claim. E.g., in this case the POSITA is NOT just limited to celebrity signature authentication experts, because it is clear that computer expertise is also involved in the complete invention claimed. There is a relevant old old Fed. Cir. case on a patent on electronic baseball stadium signs. Many patents these days are hybrid mechanical-computer or chemical-computer inventions.