Tiffany Fobes Campion is a senior attorney, Christopher R. Drewry is partner and Joshua M. Dubofsky is partner at Latham & Watkins LLP. This post is based on a Latham memorandum by Ms. Campion, Mr. Drewry, and Mr. Dubofsky. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Universal Proxies by Scott Hirst (discussed on the Forum here).

Key Points

- In contested director elections, the binary nature of the current US proxy voting regime requires a choice between either a company’s or an activist’s slate without the ability to “mix and match” among nominees. This regime can impact voting, and thus outcomes, in proxy contests, creating risk that the company might lose its entire slate in a contested election.

- Universal proxies allow stockholders to vote for nominees of their choosing from both the company and activist slates, mitigating binary “win or lose” outcomes. [1]

- Universal proxies are generally thought to favor activists because of an increased likelihood that at least some activist nominees are elected, but in the context of activist nomination of majority- or full-board slates, there may be strategic advantages for a company to use a universal proxy.

- The SEC proposed rules to require universal proxy cards in all contested elections in October 2016. [2] While the SEC’s plans for adoption are unclear, there is a renewed interest in universal proxy cards, particularly after the SEC’s November 15 roundtable on the proxy process.

- Despite the absence of adopted SEC rules, in the 2018 proxy season some companies, like Mellanox Technologies and SandRidge Energy, Inc., took steps to use a universal proxy in proxy contests with Starboard Value and Carl Icahn, respectively. [3]

- A company’s governing documents may determine its ability to use a universal proxy when an agreement with the dissident to use a universal proxy cannot be reached.

What Is a Universal Proxy?

A universal proxy is an alternative to the proxy regime currently used in the US for contested director elections. A universal proxy allows public stockholders to vote for any combination of company and activist nominees, mimicking the voting choices that a stockholder attending a stockholder meeting would have on a ballot.

The Current US Proxy Voting Regime

Under the current US regime, stockholders voting by proxy in a contested election must make a binary choice between voting on either:

- The company proxy card, which includes only the company’s director nominees, or

- The activist proxy card, which includes the activist’s nominees and, if the activist is nominating a minority of the Board (referred to as a “short” slate of nominees), some of the company’s nominees recommended by the activist to “round out” the slate.

Stockholders must select between the nominees proposed on the company proxy card or those proposed on the activist card, and are not permitted to mix-and-match nominees from the two proxy cards. Stockholders may only mix-and-match nominees if they vote in person at the stockholder meeting—an option that few stockholders actually pursue.

Proxy advisory firms, such as Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis, often determine to support some activist nominees, driving stockholders to the activist proxy card due to the binary nature of the voting system. Although support by proxy advisory firms for a particular party’s card does not guarantee a win, it dramatically impacts the voting behavior of institutional investors, many of whom expressly follow or give significant weight to proxy advisor recommendations. In a few recent situations, ISS has sought to mitigate this “all or none” consequence by recommending “withholds” as to selected directors on the company cards, intending to clear a path for a limited number of activist nominees by reducing the size of the company slate. [4] To date, this approach has resulted in the company prevailing on all candidates. [5]

Under the current regime, there is the potential that the directors actually elected are different than those that a plurality of stockholders would have preferred. In a study of US proxy contests between 2001 to 2016, Harvard Law School Professor Scott Hirst found that as many as 15% of contested elections resulted in outcomes that differed from the preference of a plurality of stockholders. [6]

An Alternative: Universal Proxies

Rather than selecting between the company or activist slate, a universal proxy card names all of the company and activist nominees for election as directors, and provides stockholders the ability to vote for any properly nominated director nominee. Stockholders voting by proxy will still need to choose between the company or activist proxy card, but will be permitted to mix-and-match nominees to vote for their preferred candidates. As a result, stockholders are able to vote for incumbent directors that they believe should be retained and for activist nominees (if any) they would like to add to the board. Stockholder interest and corporate governance groups view universal proxies as a way of enhancing stockholder governance at public companies, and therefore generally support the use of universal proxy cards in contested director elections.

Why Do US Public Companies Not Use a Universal Proxy?

Certain provisions in the existing US proxy rules present practical challenges to the use of universal proxy cards. In particular, the Securities Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) “Bona Fide Nominee Rule,” stipulates that a proxy card cannot confer authority to vote for any director nominee if that nominee has not consented to being named on that proxy card and in the related proxy statement, and to serve if elected. This means to use universal proxy cards in a contested election, a company and activist need to obtain the consent of the other party’s nominees. In past proxy contests, this consent has rarely been provided, particularly at a point in the contest when one party may view the universal proxy card as favoring the other party.

In October 2016, the SEC proposed rules to modify the Bona Fide Nominee Rule and require the use of universal proxy cards in all contested elections. Many public companies and their representatives have voiced concern that the proposed rules would disproportionately favor activists and, perhaps as a result, the SEC did not appear to be advancing the rule making process. However, at the SEC’s November 15 roundtable on the proxy process, academics, proxy solicitors, major institutional investors, and an organization representing corporate secretaries and business executives all voiced support for universal proxy cards if some minor modifications were made to the proposed rules. [7] During the roundtable, SEC Chairman Jay Clayton specifically cited universal proxy cards as a key item of interest and follow-up for the SEC staff.

To date, universal proxy cards have mostly been used for companies incorporated outside of the US. The first instance of a widely held, large-cap US company using a universal proxy card occurred in June 2018 at SandRidge, an oil and natural gas exploration and production company based in Oklahoma, in its full-board proxy contest with Carl Icahn.

Why Would a Company Want to Use a Universal Proxy?

Each proxy season, many public companies find themselves in a situation similar to SandRidge—facing a proxy contest for control of the board. Since 2014, there has been an average of 88 proxy contests for board seats each year, and activists sought board control in an average of 32% of those contests. [8] In proxy contests for control of the board, a company could consider using a universal proxy that allows stockholders to mix-and-match candidates as an alternative to the current binary choice between the company’s slate or the activist’s control slate. In the context of majority- or full-board contests in particular, Hirst’s study of proxy contests found that removing the binary proxy voting mechanism would likely result in stockholders electing more management nominees and fewer activist nominees. [9]

In addition, companies facing a proxy contest for control of the board should consider the influence and practices of proxy advisory firms. If the proxy advisory firms wish to see any degree of change at a company, they are typically willing to support some activist nominees. As activist nominees are typically not included on a company’s proxy card under the binary regime, activists can transform an advisory firm’s support for “some change” at a company into a real threat of a change of control of the board. With a universal proxy card, proxy advisory firms can recommend less than all of the nominees proposed by an activist’s change in control slate, rather than being forced into the binary “all or none” recommendation. However, if the various proxy advisory firms recommended for different nominees it may ultimately facilitate the election of more activist nominees than any one proxy advisory firm recommends (see below: A Cautionary Tale: What Happened When a US Company Used a Universal Proxy?).

Again, universal proxies likely will facilitate at least some activist nominees being elected to the board and thus may favor activists on an absolute basis—but may work to the advantage of a company facing a change in control slate. Absent such circumstances, a company likely will continue to prefer the traditional binary proxy card structure.

How Can a Company Use a Universal Proxy?

Generally speaking, three possible paths exist to obtain the director nominee consents required by the SEC’s Bona Fide Nominee Rule and thus enable a universal proxy.

Option 1: In the context of a contested election, negotiate to use a universal proxy card

- A company and an activist engaged in a proxy contest can agree to use universal proxy cards and require their respective director nominees to consent to be named on both proxy cards.

- In reality, due to the contentious nature of proxy contests and the complex strategy inherent to the binary voting regime, companies and activists rarely reach agreement on this issue.

- For example, either the company or the activist denied the request to use a universal proxy card in recent contests at ADP, Destination Maternity, DuPont, GrafTech International, Shutterfly, Target Corp., and Tessera Technologies.

Option 2: Adopt bylaws requiring director nominees to consent to inclusion in a company’s proxy

- More than 80 companies have adopted advance notice bylaws that require each director nominee to consent to be named as a nominee in the company’s proxy statement and associated proxy card, and to serve if elected. [10] Modern bylaws also require each director nominee to complete a written questionnaire in a form provided by the company with respect to the nominee’s background and qualifications, which can supply the necessary information for the company’s proxy statement.

- This may allow a company to use a universal proxy card in a contested election—if it so desires and at the company’s option—without the explicit agreement of the activist described in Option 1.

- These bylaws remain untested under Delaware law and the corporate laws of other states.

- In contrast, requiring director nominees to consent to be named as a nominee in the company’s proxy statement and associated proxy card as part of a director nominee questionnaire without the supporting bylaw language has been subject to litigation in Delaware and may not be upheld by Delaware courts (See Engaged Capital Flagship Master Fund, LP v. Rent-A-Center, Inc., C. A. No. 2017-0165-JRS (Del. Ch. Mar. 10, 2017)). [11]

- The SEC staff has suggested that activist nominees included in a company’s universal proxy would become “participants” in the company’s solicitation. This would necessitate expansive disclosures of information that the company would likely not have access to, absent comprehensive questionnaires mandated by the company’s bylaws or disclosures with respect to activist nominees made in proxy statements filed by the activist.

Option 3: Adopt bylaws requiring all parties to use a universal proxy card in contested elections

- A company could adopt bylaws mirroring the SEC’s proposed universal proxy rules, which require all parties to use a universal proxy card in contested director elections.

- In addition to the consent and information requirements of the bylaw discussed in Option 2 above, these bylaws would address logistical details for the proxy cards, such as the order of nominees and font style and size.

- Recently, Mellanox—an Israeli, NASDAQ-listed company based in California that serves as a leading supplier of computer networking products—proposed, and its stockholders ultimately adopted, such a provision in connection with its proxy contest with Starboard Value. The provision, added to Mellanox’s governing documents, requires universal proxies in all contested director elections. Ultimately, Mellanox and Starboard reached agreement and did not proceed with filing contested proxy materials or using a universal proxy. However, universal proxies will be used for any future contested election at Mellanox.

- To date, no company incorporated in the US has adopted a universal proxy bylaw, and none have been tested under Delaware law or the corporate laws of other states.

- Be aware that requiring a universal proxy card in all contested elections may result in the election of activist nominees, even if an activist does not have a strong case or lacks the support of proxy advisory firms.

When Should a Company Consider These Options?

While Option 1 can only be used in the context of a proxy contest, most US companies could unilaterally implement, without stockholder approval, the bylaws described in Option 2 or Option 3 above. Universal proxy cards are generally considered stockholder-friendly, however unilateral adoption of new bylaws in the context of an ongoing proxy contest could be considered defensive or to have an impact on stockholders’ ability to vote in an election of directors. Therefore, adoption in that context may be subject to additional scrutiny if challenged in court, or may be a rallying point for certain stockholder groups. In the view of the authors of this post, companies can materially enhance their ability to use a universal proxy pursuant to their bylaws by adopting bylaws facilitating the use of a universal proxy and enhancing their director nominee questionnaires before an activist campaign has been launched or a proxy contest has been initiated. Under current policies, proxy advisory firms and most stockholders would likely have a neutral or positive reaction to the adoption of such bylaws outside of an ongoing activist campaign.

Further, companies unilaterally adopting the bylaws described in Option 2 or Option 3 above should consider the potential for future SEC review of the underlying procedures and mechanics, and be cognizant that such review would likely occur during an active proxy contest. In this vein, the SEC staff’s review of Mellanox’s proposed universal proxy provision and other related proxy statements has been detailed and deliberative.

A Cautionary Tale: What Happened When a US Company Used a Universal Proxy?

SandRidge, in its full-board proxy contest with Carl Icahn, was the first widely held, large-cap US company to use a universal proxy card. While each proxy contest is unique and the outcome depends on a variety of factors, the SandRidge proxy contest can be considered an insightful example, and may be viewed as a cautionary tale of the potential outcomes that may follow implementation of a universal proxy card.

SandRidge was able to use a universal proxy card because Icahn’s nominees, perhaps inadvertently, provided the consents required by the Bona Fide Nominee Rule as part of Icahn’s nomination materials. However, Icahn did not have the reciprocal necessary consents from the company nominees, and thus was unable to use a universal proxy card.

To fill seven seats on the board, SandRidge asked that stockholders vote for five incumbent directors and any two of Icahn’s four independent nominees. SandRidge noted that the company previously vetted and offered board seats to two of those nominees during settlement negotiations.

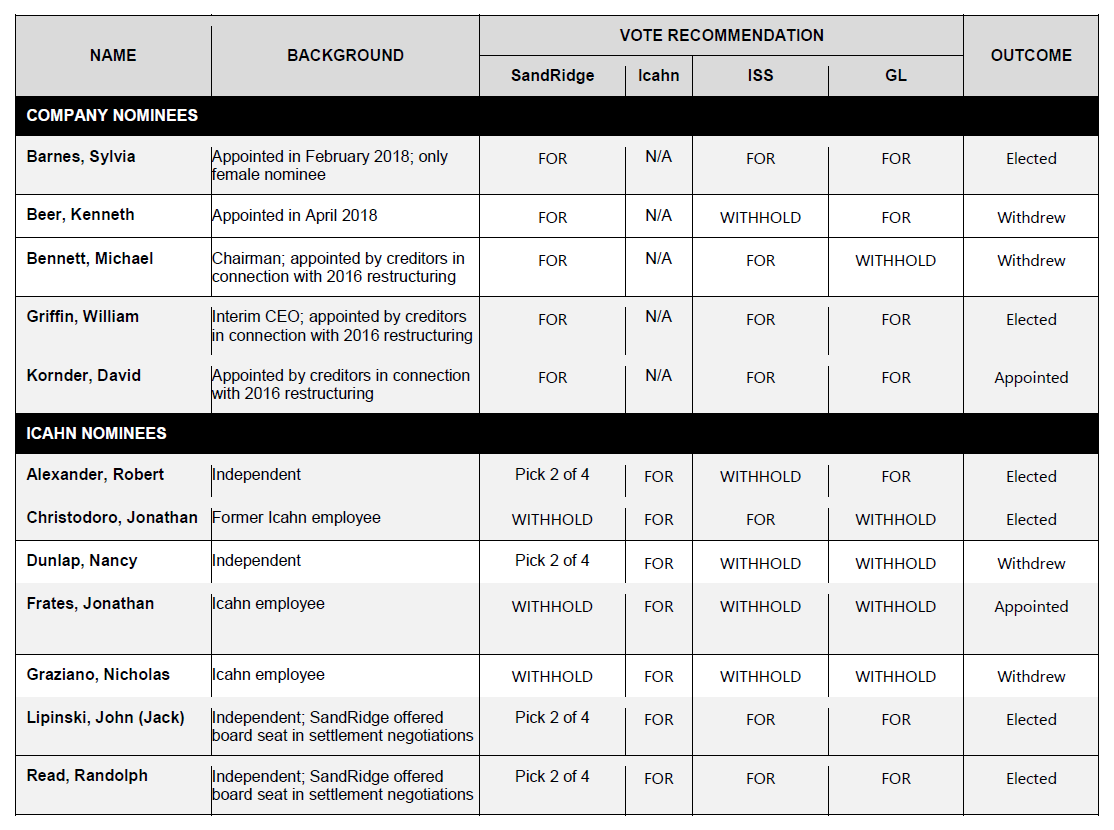

Ultimately, ISS and Glass Lewis each recommended that stockholders vote on the SandRidge universal proxy card, but, rather than the five plus two split SandRidge sought, ISS and Glass Lewis each recommended four incumbent directors and three of Icahn’s nominees. Both ISS and Glass Lewis supported the two previously vetted independent Icahn nominees. However, the proxy advisory firms were split on which third Icahn nominee to recommend and incumbent director not to support. This split resulted in a confusing, and perhaps outcome determinative, matrix of recommendations, as summarized in the below table.

Icahn capitalized on the split recommendation, encouraging stockholders to vote for the four Icahn nominees who were recommended by at least one of the leading proxy advisory firms.

Icahn’s strategy ultimately succeeded. All four of the Icahn nominees that received the recommendation of either proxy advisory firm were elected and the incumbent directors that failed to receive the recommendation of both proxy advisory firms were not elected. Six nominees (four Icahn and two incumbents) were clearly elected and, considering the results for the seventh seat were too close to call as of the close of the polls, SandRidge and Icahn negotiated a settlement to expand the board to eight seats and appoint one additional incumbent and one additional Icahn nominee. This resulted in a five-three split, with Icahn nominees controlling the board. In voting for all of the recommended Icahn nominees, stockholders appear to have ignored the proxy advisors’ strong warning that Icahn should not receive board control and deserved only three, or a minority, of the board’s seats.

Again, this experience does not dictate whether a universal proxy card is appropriate in other circumstances, but does caution that a universal proxy is not a “silver bullet” for companies facing majority- or full-board proxy contests, and that using a universal proxy can result in unpredictable outcomes.

Conclusion

Universal proxy cards may provide a strategic advantage to public companies in majority- or full-board proxy contests by permitting stockholders to mix-and-match company and activist director nominees as an alternative to supporting an activist’s change in control slate. However, current US proxy rules do not permit use of a universal proxy card without the consent of all director nominees named in the universal proxy. Despite recent indications of interest in universal proxy cards, it is unclear when the SEC may adopt rules requiring universal proxy cards in contested elections. A company’s governing documents may enable that company to avail itself of the potential strategic benefits of a universal proxy card in the event of a proxy contest. Accordingly, public companies should consider their defensive posture with respect to activism and, with assistance from their outside legal counsel, the paths to utilizing a universal proxy outlined above, prior to the initiation of an activist campaign.

Endnotes

1See Scott Hirst, Harvard Law School, Program on Corporate Governance, Universal Proxies, 35(2) Yale J. on Reg. 71 (forthcoming, last updated Sept. 25, 2017), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2805136.(go back)

2See Universal Proxy, Release No. 34-79164 (October 16, 2016) [81 FR 79122 (November 10, 2016)], https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2016/34-79164.pdf.(go back)

3Latham & Watkins advised Mellanox in connection with the consideration and implementation of its universal proxy proposal and Mellanox’s proxy contest defense against Starboard Value.(go back)

4See ISS’ recommendations for the 2017 director elections at: (1) Automatic Data Processing, Inc. contested by Pershing Square Capital Management, (2) Deckers Outdoor Corporation contested by Marcato Capital Management, and (3) Cypress Semiconductor Corp. contested by founder and former CEO TJ Rodgers.(go back)

5In the two situations that went to a vote, Automated Data Processing’s contest with Pershing Square and Deckers Outdoor Corporation’s contest with Marcato Capital Management, stockholders elected the entire company slate without modification. Whether stockholders disagreed with, or simply did not follow the nuance of, ISS’ recommendation is unknown.(go back)

6See Hirst.(go back)

7Primarily, interest groups have voiced a desire to increase the number of stockholders a dissident must solicit to use a universal proxy card.(go back)

8SharkRepellent.net data as of November 14, 2018 based on scheduled or anticipated meeting date.(go back)

9See Hirst.(go back)

10See, e.g., the bylaws of Automatic Data Processing, Square, Inc. and Tableau Software, Inc.(go back)

11In a 2017 proxy contest, Rent-A-Center, Inc. deemed the nomination materials submitted by Engaged Capital to be deficient due to the nominees’ failure to consent to being named in Rent-A-Center’s proxy statement, as required by Rent-A-Center’s director questionnaire. Engaged filed a lawsuit against Rent-A-Center in the Delaware Court of Chancery seeking an order declaring Engaged’s nomination materials to be valid without such consent and to prohibit Rent-A-Center from including Engaged’s nominees in the company’s proxy statement. The court granted Engaged’s motion to expedite the action, noting that there was the potential that Rent-A-Center’s actions restricted or inhibited the stockholder franchise, creating irreparable harm, and thus the matter was ripe for a decision. However, before the court made a decision on the merits, Rent-A-Center notified Engaged that it would not be including the dissident’s nominees in its proxy materials, rendering the claim moot. It is unknown how the court would have held on the merits.(go back)

Print

Print