Prime Minister Narendra Modi may have shown commitment to quickly conclude the discussion around Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, or RCEP, but this partnership agreement can derail his yet to take off Make in India programme. The partnership will have an impact on sectors such as steel, pharmaceuticals, e-commerce, food processing, agriculture, intellectual property, and food security. PM Modi especially wants to develop some of these sectors in the domestic market. So, the biggest challenge in RCEP negotiations is to seek markets for global majors in such a way that it doesn't promote shifting the manufacturing base.

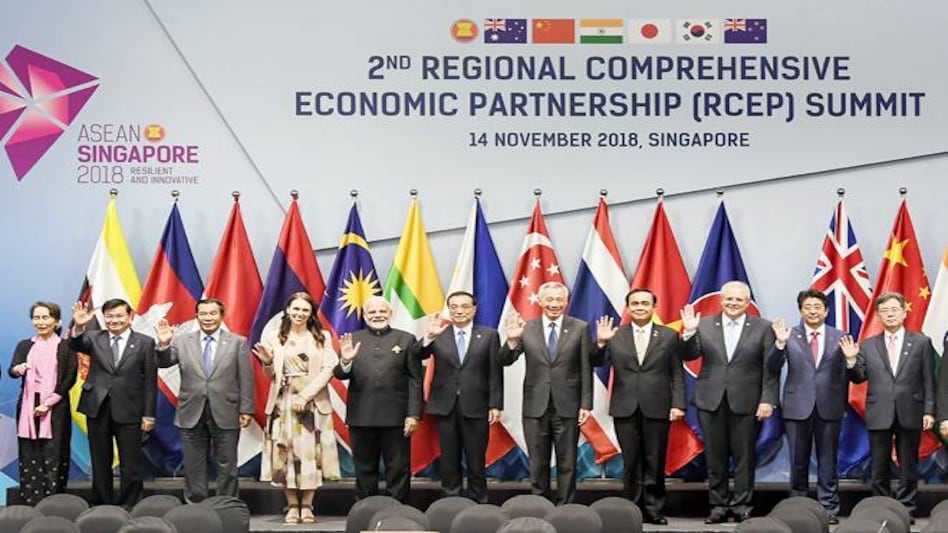

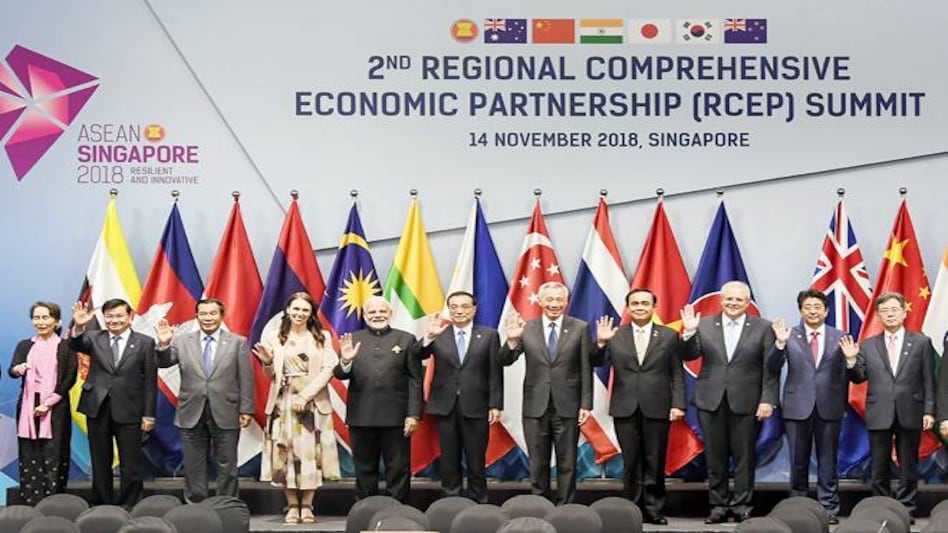

Once concluded, this multilateral agreement will cater to half of world's gross domestic product (GDP) (half of the world's population) and will be the next biggest trade pact after the agreement on Arthur Dankel's draft to upgrade General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Apart from the 10 member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), other RCEP signatories include China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand. The progress of the partnership is being closely monitored by most trade observers globally, especially when considering the US-China trade war.

The other RCEP members want New Delhi to sign the draft and look for an early conclusion. But PM Modi can ill-afford this in an election year, especially at a time when the macroeconomic indices are showing a grim picture. The current account deficit (CAD) touched 2.8 per cent of GDP, and the agreement in the present state of negotiations would mean forgoing a substantial part of the revenues. This further implies that the government needs to be confident on the GST numbers so that it can compensate for the loss. Apart from most trade pundits in New Delhi, BJP's ideological parent RSS is vehemently opposed to signing the deal, calling it a 'suicide trap'. There are reports from Singapore suggesting a substantial conclusion to the deal, but New Delhi is confident that 'this seems unlikely'.

PM Modi's presence in Singapore at this juncture means he is exerting pressure on member countries to further accommodate India's apprehensions. The presence of China creates apprehensions, especially when it is well documented that the country enjoys manufacturing surplus and is already dumping its products across the world, including in India. Apart from China, India is also losing out to financial and technological hub of Singapore, agriculture and dairy majors Australia and New Zealand, plantations of South East Asian countries, and pharmaceutical trade with China and the US. With e-commerce as part of the discussion, the Indian resistance at WTO of not letting the discussion on digital trade will weaken. India floated the e-commerce policy draft, but it will not help PM Modi's regime bring in changes if e-commerce multilateral agreement (part of RCEP negotiations) is signed.

Many of these RCEP countries are also resisting India's offer on export of services. They want India to accept provisions on domestic regulations in services. The free movement of investments will benefit investors in the US, Singapore, Japan and China, but very few Indians will be taking advantage of this.

At RCEP too, the elephant in the room is China's manufacturing surplus. China already accounts for half of India's total trade deficit. In fiscal year 2017/18, the trade deficit with China was $63 billion. China poses a great threat to not only existing industrial goods manufacturers, but also the country's small and medium entrepreneurs. India made a suggestion to offer 74 per cent of the goods at zero tariff to RCEP members. However, the reports coming in from Singapore suggest that China, New Zealand, Australia, Japan and South Korea along with some ASEAN countries are pushing India to improve this offer.

There are some valid concerns. Abhyuday Jindal, Managing Director at Jindal Stainless -- India's biggest stainless steel manufacturer -- is already jittery that New Delhi may agree on zero tariff on steel import. "This move will open flood gates of Chinese imports into India," he said. He is not wrong. The entire steel industry is lobbying to plug holes in the Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Korea and Japan, which hurts their balance sheets. They say that these agreements were envisaged to promote trade between the two countries, but trade remained largely one-sided.

The current government's agenda is to develop India into a manufacturing hub, to not only boost the economy, but also create jobs. But the present structure of RCEP puts agriculture, horticulture, dairy and food processing in a vulnerable situation, especially from imports from New Zealand and Australia. New Delhi is also worried that the RCEP will open backdoor negotiations and may lead to the country losing out on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreements. This may result in giving way to global majors in agriculture seed and pharmaceutical manufacturing. India has the world's biggest generic drug manufacturing capacity. Here, India is getting support of several ASEAN countries.

New Delhi is confident that at present, protecting the interest of Indian entities with 'essential and passive' protectionism is the path ahead and PM Modi must endeavour on this.

Copyright©2024 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today