Britain’s investment law ensnares Chinese deals amid broader reviews of foreign transactions

- A year on, Britain’s answer to CFIUS has been used to review dozens of acquisitions involving foreign buyers, including companies with ties to some of Britain’s closest allies

- Companies with links to China, Hong Kong and Russia have all seen deals blocked by the British government since the law took effect in January 2022

From a French billionaire to a Dutch semiconductor maker whose parent firm is Chinese, dozens of businesses have found themselves caught in the cross hairs since Britain enacted a new law last year to protect investments and purchases in sensitive sectors, such as defence and technology.

However, the British regulatory change has proven to be much broader than some initially anticipated, spurring hundreds of mandatory notifications for review and prompting oversight of deals by home-grown investors in Britain and companies associated with traditional allies, such as France and the US, according to legal experts.

“There has been a significant increase in state intervention in, and review of, business transactions in the United Kingdom, including for international transactions involving targets with limited activities in the United Kingdom,” Jones Day lawyers Mark Jones and Jason Beer said in a white paper this month.

The law is not limited to transactions involving foreign entities or direct investments, meaning filings for some licensing agreements, financing arrangements or insolvency proceedings could trigger a mandatory review, the Jones Day lawyers said. “The NSIA regime is a broad investment control regulation,” they added.

The legislation, which went into effect on January 4, 2022, replaced the national security provisions of the Enterprise Act and gave British officials broader powers to review a range of transactions, including minority investments, acquisition of voting rights and acquisition of assets including intellectual property.

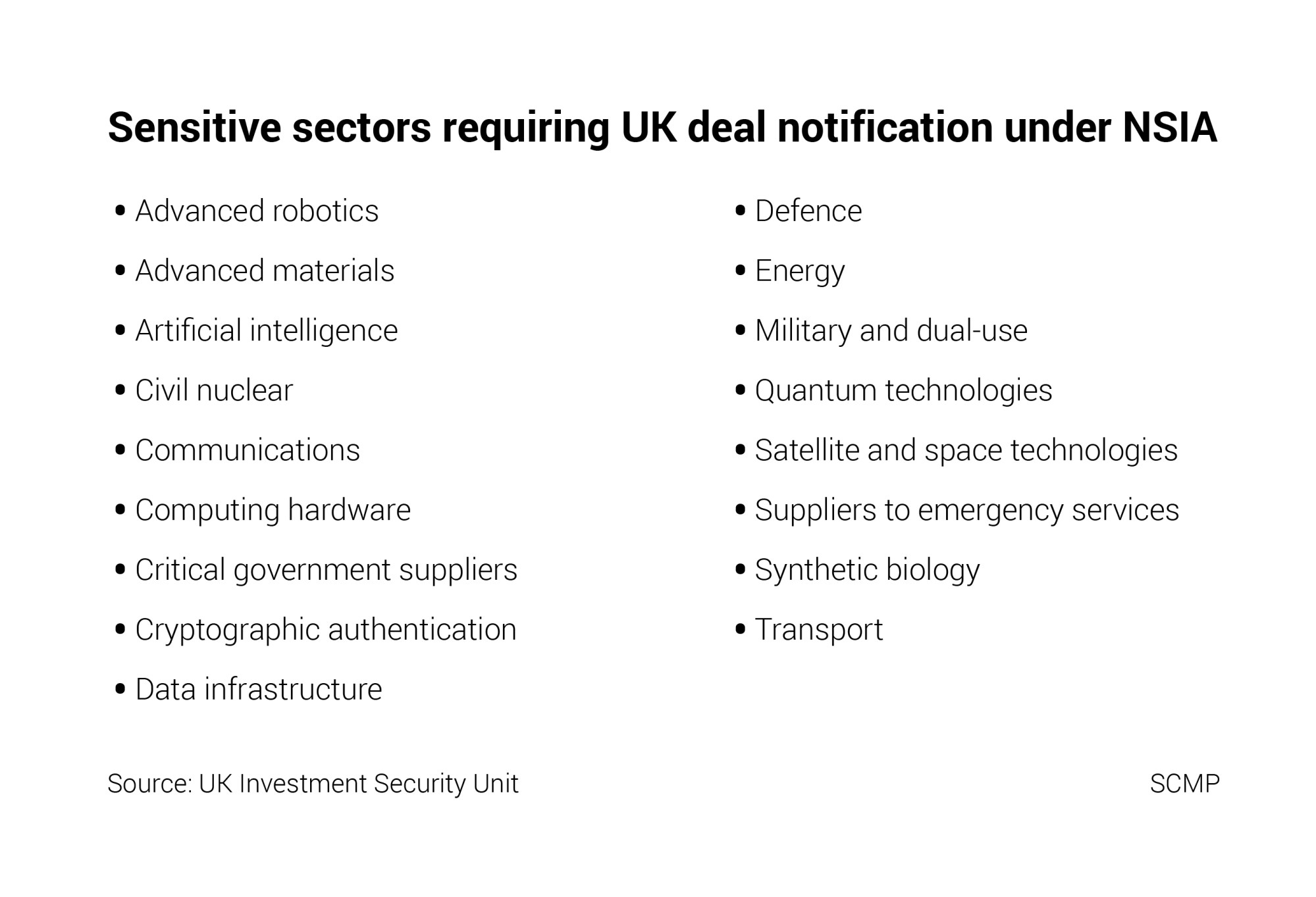

As part of the rules, acquirers in 17 sensitive economic sectors, including advanced robotics, artificial intelligence and data infrastructure, are required to notify the government about significant transactions for review. Failure to do so could result in criminal and civil penalties and having the transaction voided, up to five years later.

It is unclear exactly how many transactions were reviewed in total in the law’s first year – the government has only released data for the first three months of 2022 and is not expected to file its next update until later this year.

Since July, the government has issued 17 public decisions regarding its reviews, blocking five transactions and restricting information sharing or adding other caveats in another eight deals. Companies with links to China, Hong Kong and Russia have all seen deals blocked by the British government since the law took effect.

The application of the law has been a broad one.

In May, the government issued a so-called call-in notice for the national security review of a deal by billionaire Patrick Drahi’s Altice Group to increase its share in BT Group, formerly known as British Telecom, from 12.1 per cent to 18 per cent.

Drahi, who holds French, Israeli and Portuguese citizenship, has built a telecommunications empire through debt-heavy buyouts in France, Portugal and the US.

Altice, which first took a stake in BT in 2021, was ultimately allowed to keep the bigger interest in the telecommunications company, but the review raised questions among lawyers and investors about the broad powers of the law.

The government also reviewed on national security grounds, but took no action in October, a move by Czech billionaire Daniel Kretinsky to increase his investment vehicle’s stake in the publicly listed parent of Royal Mail, which operates the nation’s postal service.

“The regime is not limited in scope to perceived ‘hostile’ states, as investors from the UK and US as well as China, Hong Kong and UAE [United Arab Emirates] have been caught by the legislation,” Nikki Blair and Wendy Saunders of the law firm Lewis Silkin said in a client note recently.

In July, for example, the British government signed off on the acquisition of Sepura, a provider of digital radio systems based in Cambridge’s technology hub, by London private-equity firm Epiris.

As part of a final order in the matter, Epiris and Sepura, however, were required to implement enhanced controls to protect sensitive information and technology, and ensure British capabilities in repairing, servicing and maintaining devices used by emergency services in Britain.

Sepura has more than 2 million devices in use in more than 100 countries, and said it is a market leader in Britain, the Netherlands and Germany.

Another deal that saw the British government intervene in December was China Power International Holding’s 90 per cent acquisition of the Hong Kong parent of XRE Alpha, a shell company with ties to the British electricity industry.

On December 5, the government imposed a series of conditions, including restrictions on information sharing with China Power and limiting management of power sales to government-approved operators.

In its white paper, Jones Day said the British government’s liberal jurisdictional rules regarding deals have made it more challenging for private-equity funds and other investment managers to market and secure funding, as investors are reluctant to proceed if there is a slight chance of a NSIA notification being triggered.

“In some cases, investors purchased less equity or voting rights than they otherwise would have to ensure they fall below the mandatory 25 per cent notification threshold,” Jones and Beer, the Jones Day lawyers, said.

Direct or indirect acquisition of ownership stakes of more than 25 per cent, more than 50 per cent or more than 75 per cent interest or voting rights in one of the 17 sectors requires mandatory notification to the government.

“The National Security and Investment Act has strengthened the UK’s ability to investigate and intervene in mergers, acquisitions and other types of deals that could threaten our national security,” a British government spokesperson said. “Our regime ensures national security is protected while remaining both proportionate and transparent, keeping the UK firmly open for business.”

However, the new rules appear to have weighed on deal activity in Britain, with the value of deals falling to its lowest level since 2019 and transaction volumes slipping among US, EU and Chinese acquirers, according to data from Refinitiv.

The overall value of inbound deals in Britain fell by 56 per cent last year to US$147.1 billion after an uptick in post-coronavirus pandemic activity in 2021, according to Refinitiv, the data provider owned by the London Stock Exchange Group.

The amount of Chinese transactions declined even more sharply, with the value of deals slipping from US$3.3 billion to US$774.7 million, according to Refinitiv. Other than at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, it was the slowest period for deals by Chinese acquirers in Britain since 2015.

The year-old law was passed by parliament amid a period of increasingly tense relations between Beijing and London.

Members of Sunak’s Conservative Party would like him to go further and label China a “threat” in a refresh of 2021’s integrated review of defence and diplomatic strategy. The results of the refresh are expected to be announced later this year.

Since the beginning of last year, the British government has blocked two semiconductor deals by China-linked acquirers, the sharing of motion camera technology between the University of Manchester and a Beijing company and a deal where a Hong Kong company would acquire a Bristol electronic design software maker. It also forced the sale of regional broadband provider Upp by its Russian oligarch-backed owner LetterOne using the NSIA.

Nexperia agreed to the deal for the financially strapped Newport Wafer in 2021, but British politicians had raised concerns about Nexperia’s ultimate parent, Wingtech Technology, based in the Zhejiang provincial city of Jiaxing, and listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

Nexperia, which had been Newport’s second-biggest shareholder since 2019, insisted it was a Dutch-run company and had no intention to close the Newport facility or move its technology to China. The company, based in Nijmegen in the Netherlands, said it had invested more than £160 million in Britain since 2021.

Shanghai investment group behind £28 million purchase of UK chip spin-off

“This should mark the beginning of delivering policies that strengthen British national security and protect our leading tech companies and research from falling into the hands of our competitors, and states who are hostile to the rule of law,” Alicia Kearns, the chair of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee and a China critic, said in a tweet after the deal was blocked.

Nexperia said it was “genuinely shocked” by the decision and has filed with the High Court for judicial review of the decision.

“This decision sends a clear signal that the UK is closed for business,” said Toni Versluijs, Nexperia’s UK country manager. “The UK is not levelling up but levelling down communities like South Wales.”