In September of 1997, Final Fantasy VII was released for the original Playstation in North America. The watershed game swapped the series’ swords-and-sorcery and sun-dappled-forests motif for bombs and machine guns in a dark, rainy futuristic urban metropolis. It was a time before the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter movies, a time when sci-fi and cyberpunk were ascendant and the stodgy old wizards and sword-wielding heroes of fantasy worlds reeked of the distant past (say, 1992).

While FFVII wasn’t the sequel I had been expecting, eventually even SNES JRPG diehards like me came to appreciate the change in style, as well as the sheer scale and ambition of what it was trying to accomplish. Nobody had ever told a story that big on consoles, and moving away from the 2D sprites into a (sort of) 3D world was a huge technical step forward for RPGs and gaming in general.

Thanks to a corrupted third-party memory card, I was never able to beat the game on that original hardware. It wasn’t until this year that the Switch re-release (and coronavirus-imposed lockdown) gave me the chance to breed the chocobos, find the KOTR materia, destroy JENOVA, and kill Sephiroth.

That’s when I found that, over 20 years after the initial release, FFVII’s ending still had the power to shock. Whatever I was expecting from the game’s conclusion, it wasn’t what I took to be the end of both human life and civilization.

Gaming for the environment

The final cut scene is set hundreds of years after the events of the endgame, when Cloud and the gang are, presumably, very dead. We see party member/space coyote Red XIII (whose species lives for thousands of years) and his children roaming the weedy ruins of the world’s forgotten, unpopulated metropolis of Midgar.

As nature reclaims the land and the coyotes frolic, not a single sign of human life is seen. It appears that mankind and all traces of its civilization had perished from the earth due to the summoning of METEOR.

It’s a shocking narrative moment, especially compared to the endings of most ’90s video games. Hooray, you beat the game, kids! Also, humanity had a nice run, yeah?

But the ’90s did see environmental themes popping up all over gaming. Niche games like Ecco the Dolphin made this explicit, but even iconic hits like Sonic the Hedgehog asked the player to free imprisoned and adorable forest animals that Dr. Robotnik was attempting to transform into cyborgs. As they return to their habitat, the birds and squirrels bound and flutter offscreen, chirping cheerfully.

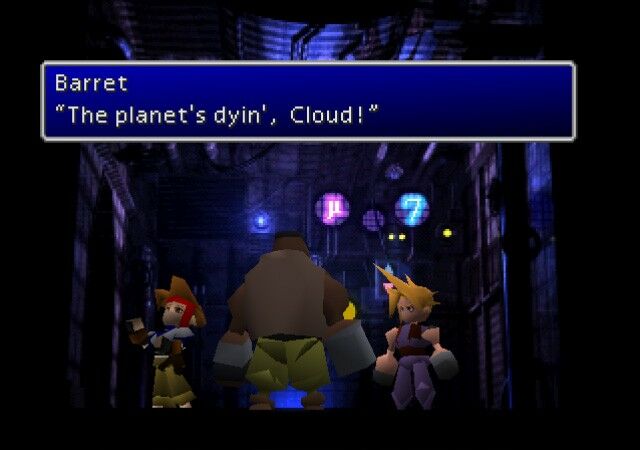

Final Fantasy VII, however, made an extraordinary leap in asking the player to assume the role of violent ecoterrorists bent on blowing up a reactor inside a densely populated metropolis. One of the game’s early, epic cutscenes ends with the bomb going off and the reactor being destroyed. Sure, some people died as “collateral damage,” but it’s OK… you’re the good guys!

In the game’s finale, the planet itself is saved, but at what appears to be the cost of all human life. No matter how you choose to interpret the ending, it's thought-provoking.

With almost 13 million units sold worldwide, FFVII had a huge influence on an entire generation of gamers. It also helped move Final Fantasy, and RPGs, into the Western mainstream. It’s easily among the best-loved and most influential games, ever.

But its impact wasn’t limited to the industry—the game’s radical environmental themes and Shinto-tinged philosophies wound up influencing a generation of environmentalists.

Pay attention, children

Bobby Pembleton, now an enterprise executive at a top European university (and a member of my international Mario Kart online group) is among those who found that FFVII’s environmental message stuck with him. And he’s got the tattoo to prove it.

"Me and both of my siblings were totally radicalized by the game," Bobby told me. "When we first finished it back in the day, our takeaway was, 'Oh, civilization ended, and this is a good thing.’”

“We hadn’t seen an uncertain ending (in any media); that level of complexity was new to us,” he added. “It took a few days to sink in, but we concluded all humans were dead, and this was a good ending.”

Bobby’s youngest sibling, Jaclyn Dean, now works in healthcare. Jaclyn was 8 years old at the time, so more of an observer at first, but recalled, “I would actually assign characters to my brothers, enlist them to do character voices with me, and really act out the dialogue to immerse us in the story.”

After a year or two Jaclyn would pick up the game herself. “As I developed my agency, I thought, ‘hey I can do this, too, girls can play video games!’” Eventually she went as far as printing out a strategy guide, becoming the first Pembleton to 100 percent the game.

Dylan, the middle Pembleton child who now works in the film industry, recalled that the ending made them all feel that “we need to be stewards of the land, like these ancient talking coyotes. Our takeaways were that major industrialization is bad, and understanding how the lifestream and the planet works is much more important—because look how cute those coyote puppies are!"

Dylan says it’s hard to overstate the game’s impact on his choices as an adult. “FFVII affects the way I vote... everywhere I’ve lived, I’ve started a community garden. I’ve worked as a horticulturist. I know what I’m trying to do, and yeah, it’s essentially based on the philosophies of FFVII."

“At the time we didn’t realize [Final Fantasy VII] could be an allegory for what was going on with extraction of capital from working masses, extraction of oil and resources from the planet, the distribution of that to the top .01 percent, up in Midgar,” Bobby remembers. “It was very influential for us all. We spent two years playing the game, again and again. We left the Playstation on as we went to bed so we could drift off to that opening theme music.

“It primed us for this concept of a battle between workers and a hyper-capitalist machine hellbent on extracting every ounce of value from the planet,” he continued. “Soon after [the game came out] 9/11 happened, the Iraq war… there was an increasing comprehension [for us] that evil things were being done for the sake of making people rich.

“Twenty-five years ago playing this game, we didn’t realize how important that fight was—increasingly, [now] we do realize how important it is. Now people are going vegan, trying to help the world move to a well-being-based economic system—we’re all considering increasingly extreme actions ourselves in order to fight the fight.”

reader comments

80