In a press release yesterday, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai announced that he has proposed a set of rules for the new RF spectrum that the proposed Wi-Fi 6E standard will use. In this month's April 23 meeting, FCC members will vote on those proposed rules for unlicensed use of the 6GHz band (5.925–7.125GHz).

The Wi-Fi spectrum we already have—2.4GHz band

In the 1990s, the biggest concern for Wi-Fi users was "how far will the Wi-Fi reach." Today, the biggest concern—whether most users realize it or not—isn't how far the Wi-Fi will reach, it's how many different devices are competing for airtime. The legacy 2.4GHz band is almost entirely unusable for many urban dwellers—it's crowded with microwave ovens, Bluetooth headsets, and every Internet-of-Things device imaginable.

Making matters worse for 2.4GHz, the frequency band offers excellent range and penetration—which in an increasingly crowded modern setting is very much a bug, not a feature. A Wi-Fi device can only transmit if no other device in range is also transmitting—so increased range and penetration also means increased competition for airtime.

This competition doesn't exist only in one Wi-Fi network, either—having a different SSID (Wi-Fi network name) and password than your neighbor doesn't keep your devices from congesting with one another. And since there are only three non-overlapping 20MHz channels in the 2.4GHz spectrum, the odds of having to fight for airtime with neighbors' devices as well as your own are very high.

The Wi-Fi spectrum we already have—5GHz bands

5GHz—an additional spectrum available to 802.11n (Wi-Fi 4), 802.11ac (Wi-Fi 5), and 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6) devices—has considerably lower range and penetration. Again, for most users, that's a good thing—if your device can only "hear" a couple of rooms and walls away, that means you're less likely to be fighting with neighboring networks for airtime.

There's also more total spectrum available in 5GHz than there was in 2.4GHz. This advantage is largely negated by the fact that 5GHz channels are typically much wider than 2.4GHz channels.

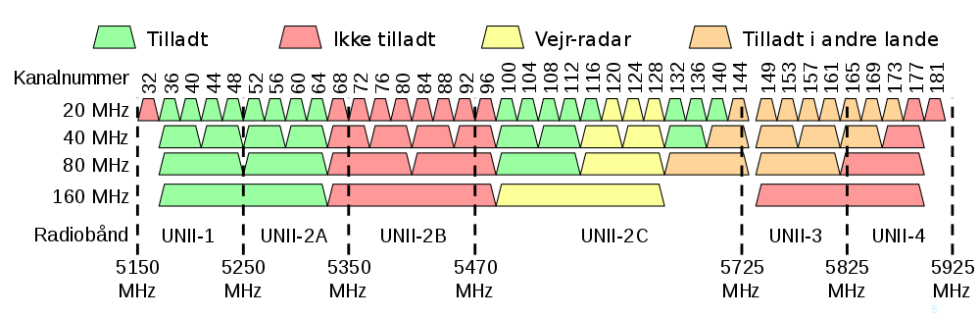

Use of the 5GHz spectrum is also complicated by DFS regulations that close large pieces of it off—either partially or entirely—to Wi-Fi devices, in order to keep them from interfering with radar. Although the spectrum technically spans 775MHz, only 140MHz of that is effectively useful for most users in the United States—60MHz in the low band below DFS channels, and 80MHz in the high band above them.

The DFS channels themselves are an uncertain grab bag of 320MHz between the low and high 5GHz bands. Use of these channels is permitted, albeit heavily regulated to prevent interference with radar systems. A large number of consumer devices refuse to use DFS channels at all, even when no radars are present.

The Wi-Fi spectrum being voted on—6GHz band

Wi-Fi 6E isn't a new wireless protocol at all—it's an expansion of the current Wi-Fi 6 standard into a new and much wider radio frequency band.The spectrum Pai's FCC votes on this month offers roughly six times the total spectrum currently available on both 2.4GHz and 5GHz bands combined and offers it in a single, contiguous band from 5.925–7.125GHz. This is enough spectrum to offer seven completely non-overlapping 160MHz wide channels.

Each separate channel can provide roughly double to quadruple the maximum performance we see from 5GHz Wi-Fi 5 and Wi-Fi 6 devices now—and do so without relying on protocol parlor tricks that may or may not actually pan out as well in real life as they did in a test lab.

The path forward for Wi-Fi 6E

Although it's technically possible for the FCC to rule against using the new spectrum at all in the April 23 meeting, this seems vanishingly unlikely. FCC Chairman Pai is far from alone in enthusiasm for the spectrum expansion; he is joined by statements from the Internet and Television Association, Broadcom, Intel, the Open Technology Institute, the Wi-Fi Alliance, and more.

As we covered in February, Wi-Fi chipset maker Broadcom has already announced the availability of the BCM-4389 Wi-Fi 6E chipset, which makes use of the new spectrum. Intel hasn't gone quite that far, but a conversation last night with Eric McLaughlin, General Manager of the company's Wireless Solutions Group, made it clear that they're not far behind, either.The draft deserves, and likely will get, unanimous approval from the FCC.

—Andrew Jay Schwartzman, Senior Counselor, Benton Institute for Broadband & Society

Intel's McLaughlin told us to expect a dual-band Wi-Fi 6E chipset from them later this year, with expected certification in early 2021. Like Broadcom's BCM-4389, the Intel chipset would use a single radio to cover both 5GHz and 6GHz spectrum, with a 2.4GHz radio for use with legacy networks.

We're thrilled to see an entire 1200MHz of spectrum released for unlicensed spectrum. That's a lot of channels... I really applaud the FCC for recognizing the need for contiguous channels. Not all WiFi 6E will be the same around the world; China and Europe aren't allocating the same amount of spectrum to the 6GHz band.

—Eric McLaughlin, VP Client Computing Group and General Manager of Intel's Wireless Solutions Group

Pai's draft Report and Order would authorize two different types of unlicensed operation. Indoor, low-power access points and devices will be able to use the full 1,200MHz available, but 850MHz will be available to higher-powered access points.

An "automated frequency coordination system" would further regulate the higher-power access points, to prevent them from interfering with incumbent, licensed users of the 6GHz spectrum. This will likely look much like current DFS regulations in the 5GHz band—with the sharp difference that the lower-power, indoor-only access points and consumer devices won't be affected by it.

Providing fewer restrictions for operation of lower powered devices is, in our opinion, a key factor in the long-term successful use of the spectrum.

An additional Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for this month's meeting proposes to open the 6GHz band to very-low-power devices—specifically including and targeting wearable augmented-reality and virtual-reality devices. The Further Notice seeks comment on power levels and other "technical and operational measures" for the separate class of very-low-power devices, with ratification of any rules on them to occur at an unspecified later date.

reader comments

120