The sLoad malware downloader, a PowerShell-based trojan first spotted in May 2018, has a new, polished version that comes with “more powerful features, posing even higher risk,” Microsoft researchers are warning.

After discovering it being used in several campaigns over the holidays, researchers have dubbed the new sLoad version “Starslord,” based on strings in the malware code. Starslord, a downloader that installs itself to the system, connects to a remote server, and downloads additional malware onto the infected system. In this, it follows an attack chain similar to the original version. However, version 2.0 includes a new anti-analysis trick and the ability to track the stage of infection on every affected machine.

“sLoad’s multi-stage attack chain…and its polymorphic nature in general make it a piece malware that can be quite tricky to detect,” Sujit Magar, with Microsoft’s Defender ATP research team, said in a Tuesday analysis. “Now, it has evolved into a new and polished version, Starlord, which retains sLoad’s most basic capabilities but does away with spyware capabilities in favor of new and more powerful features, posing even higher risk.”

The latest sLoad version comes on the heels of a previous Microsoft December research paper describing the downloader’s attack techniques, suggesting that the developers behind the malware are trying to shake off any analysis, Microsoft warned. Threatpost has reached out to Microsoft for more details regarding the victims and a timeline of the Starslord version.

sLoad Attack Chain

sLoad is known for its multi-stage nature and staple, almost exclusive use of Background Intelligent Transfer Service (BITS) for data exfiltration, payload fetching and command-and-control (C2) communications. BITS is a legitimate Windows component that uses idle network bandwidth to transfers files in the background of any running applications.

First spotted in May 2018, sLoad has been seen delivering a variety of payloads, including the Ramnit and Ursnif banking trojans, Gootkit, DarkVNC and PsiXBot, among others. Other trademarks of sLoad include its use of geofencing, which is restricting access to content based on the user’s location, determined via the source IP address, during all steps of the infection chain (including the download of the dropper, the PowerShell download of sLoad, sLoad’s communications with its C2 server, and when it receives a task or command).

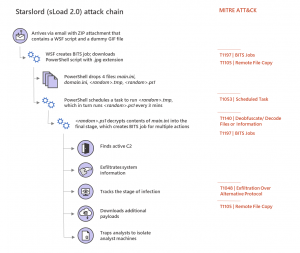

Starslord’s attack chain stays mostly the same as the original, with some small differences, researchers said. Like the original version, Starslord first arrives via email with a ZIP attachment. These attacks have previously been launched via crafted emails in the targeted country’s language, and are often personalized to include recipients’ names and addresses in various parts of the email such as email body and subject.

However, while the first version’s ZIP attachment contained a VBScript, which then ran the Powershell and decrypted the payload into the system’s memory, Starslord instead uses a Windows Script File (WSF script, or a file type used by the Microsoft Windows Script Host) that then downloads the PowerShell script with a .jpg extension.

A BITS job is then created for the Starslord PowerShell script to perform various actions. Many of these were also performed by the first dropper version, including gathering information about the infected Windows systems, sending all system information to the C2 server and downloading additional payloads.

However, while the previous version would take screenshots of the system and upload them to the C2, Starslord appears to have traded these spyware-like capabilities out for other features.

New Features

One such feature in Starslord is a tracking mechanism capability allowing it to track the stage of an infection. This tracking mechanism loops infinitely to feed the C2 the information, which researchers could be used by the downloaders’ operators to organize various infected machines into sub-groups, and then send commands to specific systems.

“With the ability to track the stage of infection, malware operators with access to the Starslord backend could build a detailed view of infections across affected machines and segregate these machines into different groups,” researchers said.

Starslord also comes with a new anti-analysis trick, allowing it to trap analysts to isolate analyst machines. This built-in function, called checkUniverse, stems from two files dropped onto the system (a randomly named .tmp file and a randomly named .ps1 file).

“When an analyst dumps the decrypted code of the final stage into a file in the same folder as the .tmp and .ps1 files, the analyst could end up naming it something other than the original random name,” researchers said. “When this dumped code is run from such differently named file on the disk, a function named checkUniverse returns the value 1.”

If the system does belong to an analyst, the files downloaded by the PowerShell script (in response to the exfiltration BITS job) are then discarded.

sLoad continues to evolve, and Proofpoint researchers in 2018 said that only months after its discovery, there were already several incremental changes to the malware dropper (such as a change at the zipped-LNK download step — so that the initial .LNK file was downloading sLoad directly without the additional intermediate PowerShell).

“sLoad, like other downloaders we have profiled recently, fingerprints infected systems, allowing threat actors to better choose targets of interest for the payloads of their choice,” the Proofpoint research team said at the time. “In this case, that final payload is generally a banking trojan via which the actors can not only steal additional data but perform man-in-the-browser attacks on infected individuals. Downloaders, though, like sLoad, Marap and others, provide high degrees of flexibility to threat actors, whether avoiding vendor sandboxes, delivering ransomware to a system that appears mission critical, or delivering a banking trojan to systems with the most likely return.”

Concerned about mobile security? Check out our free Threatpost webinar, Top 8 Best Practices for Mobile App Security, on Jan. 22 at 2 p.m. ET. Poorly secured apps can lead to malware, data breaches and legal/regulatory trouble. Join our experts from Secureworks and White Ops to discuss the secrets of building a secure mobile strategy, one app at a time. Click here to register.