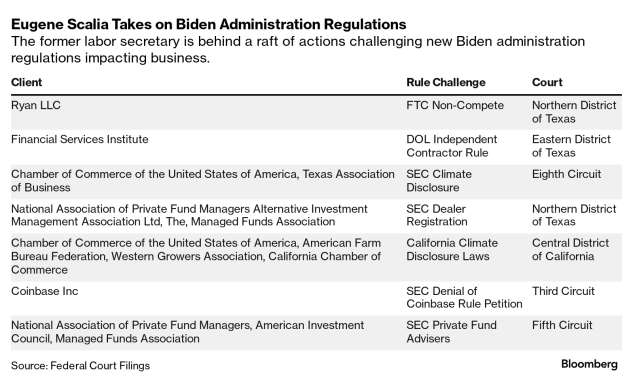

- Scalia backing six challenges of Biden administration rules

- Son of conservative icon runs firm’s administrative law group

Scalia, son of the late conservative icon and Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, since September has mounted six challenges to federal authority on behalf of corporate interests. He’s battling pollution disclosure rules, a ban on worker non-competes, and a definition of an independent contractor that replaces one he created as US Labor Secretary.

His private practice at Gibson Dunn & Crutcher has kicked into overdrive as the Biden administration issues rules for an agenda frequently stymied in Congress and as the conservative-dominated Supreme Court directs greater hostility toward administrative power.

“It’s a bit of a perfect storm,” Scalia, 60, said in an interview. “The courts are being vigilant about the limits on agency power, and the agencies are being very aggressive in trying to push those bounds.”

The younger Scalia specializes in an arcane type of work designed to knock down rules under the Administrative Procedure Act. The nearly 80-year-old statute dictates procedures federal agencies must follow when crafting edicts, such as giving proper notice of proposals, including time for public comment, and staying in accordance with law.

Scalia first led an action under the act in 1994 against the now-defunct Interstate Commerce Commission. Challenges under the APA were so unusual then that when Scalia asked his Gibson Dunn colleagues if they had done one, no one said they had.

It “was a backwater statute,” said Dan Gallagher, a securities regulator under President Obama and legal chief for Robinhood Markets Inc.

‘Inside’ Vantage

Gibson Dunn now has an administrative law group, launched by Scalia, that specializes in fighting agency rules. It tracks with an overall spike in such cases—the number of APA challenges in 2023 was three times higher than in the same year a decade earlier, a Bloomberg Law analysis found.

“Agencies are doing a lot of the work that you would have expected Congress to do,” said Ron Levin, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “Actions taken by one administration will be very disturbing to people of the opposite persuasion, and that means you’re going to challenge.”

Scalia’s role as President Donald Trump’s labor secretary has given him a crucial “inside-the-administrative-state vantage point” in the fight against agency overreach, said Mark Chenoweth, president of the New Civil Liberties Alliance.

“It’s hardly a surprise that agencies assert powers that Congress never gave them,’' said Chenoweth, whose nonprofit group’s mission is to prevent violations by the administrative state, according to its website.

Scalia’s clients today include a mix of corporations and prominent trade groups. He’s representing the Chamber of Commerce, the powerful business lobby, in federal and state actions challenging rules that require companies to disclose certain data on their greenhouse gas emissions.

He’s also leading legal strategy for the Bank Policy Institute, a trade group for big banks, as it lobbies against credit card late fee caps and a proposed bank capital overhaul that would force the biggest lenders to raise their capital levels by 19%.

The work has proved lucrative. Scalia had a partner share at Gibson Dunn that surpassed $6.2 million before he became labor secretary, according to a financial disclosure.

‘Shadow Government’

Scalia is behind four ongoing fights with the Securities and Exchange Commission over a progressive agenda led by chair Gary Gensler. The lawyer, who boasts a 7-0 record against the agency in court, is challenging reforms covering private funds, dealers, and climate disclosures that he claims swerve beyond the securities regulator’s lane while imposing huge costs on businesses.

He is also representing Coinbase Global Inc., the largest crypto exchange in the US, as it seeks a court review of the SEC’s December decision denying a petition for a rule covering how it determines when a digital asset is a security.

“The process in rulemaking has frankly enabled rule challenges in court,” said Nicolas Morgan, president of the Investor Choice Advocates Network. “The speed, the quantity, the short notice period is just going to translate to rules that are more susceptible to challenge.”

The Gensler-led SEC squared off against Scalia in the Fifth Circuit in February over a rule requiring private funds to detail quarterly fees and expenses to investors. The agency, which didn’t respond to a request for comment, has called the rules a “flexible and measured approach to resolve problems affecting investors and their stakeholders.”

The SEC has also called its climate rule a necessary update to disclosure requirements that help investors vet risks.

Most notably, Scalia is representing a group called the Financial Services Institute in a lawsuit fighting the Department of Labor’s new rule on worker classification—a rule that rescinded an independent contractor test Scalia signed off on as Labor Secretary in 2021 before he left the agency.

“It definitely is unusual to see a government official directly challenging their successor’s work,” said Adam Pulver, an attorney at left-leaning advocacy group Public Citizen. “It acts kind of like a shadow government.”

The Department of Labor didn’t respond to a request for comment.

‘Retirement Plan in Perpetuity’

The second of nine children, Scalia graduated from the University of Chicago Law before spending a legal career weaving between Republican administrations and Gibson Dunn. He formed Gibson Dunn’s administrative law practice after becoming a partner there in 1999.

His challenges to the Dodd-Frank banking law, which imposed hundreds of new rules on businesses, were so frequent that some inside the agency called the 2010 statute “The Eugene Scalia Full Employment Act.” Even today, SEC officials expect a challenge from him when crafting controversial rules, according to a person familiar with the matter.

“If Dodd-Frank was the Eugene Scalia Full Employment Act, the Biden administration is the ‘Eugene Scalia Retirement Plan in Perpetuity,’” said Gallagher, a former SEC commissioner.

As of March, the Biden administration had issued a total of 209 economically significant rules, according to the George Washington University’s Regulatory Studies Center. By comparison, at the same point in their administrations, Trump had rolled out 124 rules and President Barack Obama 184.

Biden is attempting to act like a modern day Franklin Delano Roosevelt, despite not having the legislative majorities that allowed Roosevelt to implement his New Deal reforms, Scalia said on the Bloomberg Intelligence podcast in March. “So how does he get there? Well, it’s through aggressive, adventurous use of agencies,” he said.

Courts, however, have also increasingly encouraged litigants to try their luck challenging rules, said Xiao Wang, a University of Virginia law professor. He pointed to nationwide injunctions Republican-appointed jurists have issued in response to regulatory challenges.

On May 10, for instance, a Texas judge imposed an injunction temporarily freezing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s rule capping credit card late fees at $8. Judges are “not just willing to take these cases, but to rule in favor of challenges to administrative law,” Wang said.

The Fifth Circuit, which covers courts in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, has become a prominent venue for challenges. Scalia has filed three suits in that circuit, including two on behalf of The National Association of Private Fund Managers. The nonprofit reportedly formed in Texas shortly after the SEC released its first proposal reforming rules for private fund advisers.

“Many of the cases we’re seeing filed now are primarily disagreements of policy,” Pulver said. “Those cases didn’t get much traction 20 years ago.”

The growing skepticism toward agency rulemaking among the courts is a shift Scalia said he hopes to capitalize on.

“One big change since I started practicing is that courts now are very interested in administrative law,” Scalia said in the interview. “Years ago, it was a challenge sometimes just to get a court’s attention. Now, courts across the country are well versed and engaged with this area of law.”

Scalia has wasted no time pushing the courts. Mere hours after the FTC in April adopted a rule issuing a near total-ban on non-compete provisions in the workforce, Scalia, representing a Dallas-based tax firm, sued.

“If ever a federal agency attempted to pull an elephant out of a mousehole, this is it,” Scalia’s lawsuit said. The language echoed an expression his father coined to describe how agencies can attempt to issue sweeping policy via narrow law.

To contact the reporters on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

Learn About Bloomberg Law

AI-powered legal analytics, workflow tools and premium legal & business news.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools.