It’s bizarre but true: wire recording is the longest-lasting capture format in audio history, one that paved the way for reel-to-reel tapes and a host of others—even though most people today, and some techies included, have barely heard of it.

Invented way back in 1898 and patented two years later, wire recording was somehow still getting some limited use as late as the early 1970s, while rockets took man to the moon on an annual basis. In its wake, vinyl, with its 67 years, and CD with a mere 33, look like footling youngsters. In its none-too-brief life, "the wire" also found use in Hollywood, provided a broadcast aid to spying, helped launch digital data capture, and pioneered the new art of bootlegging—sorry, "home recording."

Wire was longer-lasting in other ways, too—whereas shellac and vinyl records would only last a few minutes per side, and the first commercial tape decks weren’t that much better, the wire recorder could get down over 60 minutes of audio.

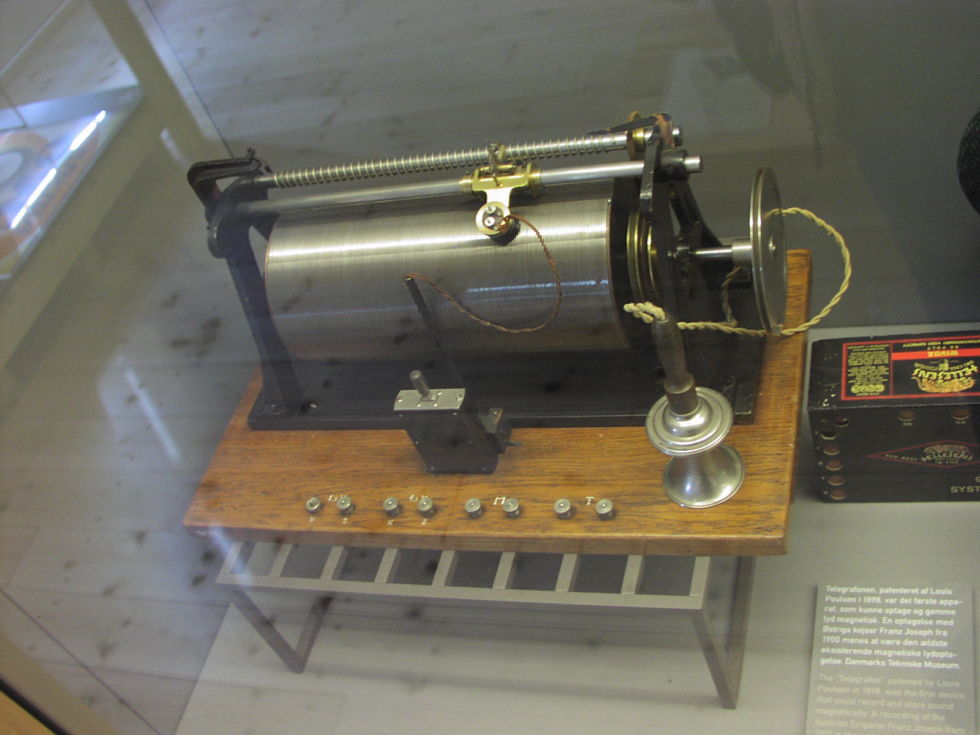

Hanging on the telegraphone

Of course, it didn’t start that way. The earliest wire device was cooked up at the end of the 19th century by one Valdemar Poulsen, a Danish-American inventor who, five years later, developed the first continuous-wave radio transmitter. This first "telegraphone," as Poulsen dubbed it, was somewhat crude, but it did have the key conceptual elements: a metal wire was pulled between spools across a recording head, which magnetised the wire in accordance with the sound signal it was receiving at that moment. In other words it recorded recognisable sound.

The American Telegraphone Company then cranked out various dictation machines, which, in terms of quality, beat the hell out of their wax cylinder rivals. And, unlike the cylinders, wire reels could be used and reused time and time again and were capable of recording for far longer. Wire recorder sales were steady but not spectacular; it was not a machine most small businesses could afford. Quality-wise, too, neither wire nor wax cylinder could come anywhere near capturing the wide dynamic range that music requires. So as 78rpm shellac records slowly but surely improved, the musical applications of wire were increasingly neglected, although they did, strangely enough, make a late comeback.

But later on, during the 1930s and again in World War II, the secret services of several nations would use wire recordings, massively sped up, to broadcast on shortwave radio to their agents in the field. The agents would be standing by, ready to "wire tape" these broadcasts, already aware of the exact tempo to play them back at. Of course, the enemy could sometimes decipher these broadcasts if they had enough experts and wire recorders with which to try speed experiments, but they were difficult enough to translate to give the receiving operatives at least a day or two head-start. For anything urgent, it was for years the simplest way of broadcasting something your agents could swiftly understand that the opposition couldn’t.

And then, after World War II, the wire—by now middle-aged—finally entered its golden age, a decade of near-dominance because wax cylinders were long gone and the new, early, tape decks were far too expensive for anyone except the rich or top sound studios. So American manufacturers Armour and Brush licensed dozens of improved wire machines across North America, Europe, Australia, and Japan. They became the kings of dictation and, later, family recordings.

One mile per hour

Most of these post-war wire machines used a speed of two feet, or 24 inches, per second (610mm/s), so an average hour-long recording would use up a spool of wire that was 7,200 feet in length (2,200m). That's well over a mile long, roughly 1.35 miles in fact, but this huge length could easily be squeezed onto a reel less than three inches (76 mm) wide, as the wire—by then made of stainless steel—was incredibly fine, with a diameter of just 0.005 inches (about 0.12mm), or slightly less than the average human hair.

Tens of thousands of wire recorders were produced and sold in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, along with almost a million miles of wire. Such mass production, and the increasing availability of second-hand devices, swiftly brought the price down to a point where it became no longer purely a dictation machine for expensive offices, but a home-recording medium that people could, and did, use to record their own voices, as well as their own music and songs off the radio—thus giving the world its first example of illegal home recording.

reader comments

108