KM: definition, history, & current trends [Personality & TKMS series]

This is part 2 of a series of articles featuring edited portions of Dr. Maureen Sullivan’s PhD dissertation.

Brooking1 defined knowledge “as information in context with understanding how to use it”. Sunassee and Sewry2 stated that knowledge is related an individual‘s emotions, values, and beliefs. To ensure that knowledge is a contribution to the performance of an organization, organizations must determine how its various forms of knowledge can be used3. Moreover, at the organizational, individual, and group levels, there are various forms of knowledge, including systemic, explicit, tacit, and implicit 4 5 6 7 8.

Explicit knowledge can be easily captured, codified, and communicated whereas tacit knowledge is associated with beliefs, values, intuition, expertise, experiences, and emotions9. Therefore, it is essential to understand the difference between tacit and explicit knowledge because different management initiatives are required to manage both types of knowledge10.

Technical solutions to implement various knowledge processes include knowledge creation, representation, storage, and sharing11. Although, these technical solutions make knowledge management (KM) implementation easier, organizations must still investigate what factors (e.g., motivation) influence an individual‘s acceptance of a knowledge management system (KMS). This investigation could include reviewing the motivational factors related to age and educational background gaps and determining if the expected benefits of KM implementation are realized12.

Knowledge management

The race to remain competitive has sparked many organizations to create knowledge management (KM) initiatives. First, defining what KM is important to further the understanding of the initiatives created by organizations. O‘Leary13 defined knowledge management as the

Organizational efforts designed to: (a) capture knowledge; (b) convert personal knowledge to group-available knowledge; (c) connect people to people, people to knowledge, knowledge to people, and knowledge to knowledge; and (d) measure that knowledge to facilitate management of resources and help understand its evolution.

Various types of global organizations and companies are investigating KM initiatives and implementing them into their business strategies14. These KM initiatives include successful implementations of social software deployment and knowledge-based repositories15. In fact, quite a few researchers have detailed the benefits of these successful KM implementations in various journals16 17 18 19.

Information communication technology was the focus in earlier KM implementations. However, today, the importance of flexibility in KM initiatives is recognized by researchers and practitioners20 21 22. Although there are many research studies outlining the importance of information communication technology usage as an enabler for KM practices, there are socio-technical issues related to KM implementation success23 24 25.

Neto and Loureiro26 stated that “despite the fact that many current implementations of KM initiatives are based on highly advanced information technologies, there are still challenges to cope with in order to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of such KM initiatives”. These challenges can lead to failures in KM implementation. Failures in KM implementation have been caused by organizational culture and other psychosocial factors, even though organizational culture and other psychosocial factors serve an important job in KM success27. Moreover, studies and surveys discussing these KM implementation failures have been documented by various researchers28 29 30.

History of knowledge management

The ASEAN Foundation publication Introduction to knowledge management31 explores the history of knowledge management.

The history of knowledge management is brief because it is a relatively new discipline, starting around the 1970s. Knowledge management came about in the 1970s because of papers published by management theorists and practitioners like Peter Drucker and Paul Strassman. These papers focus around how information and knowledge could be used as valuable organizational resources. Another management expert, “Dorothy Leonard-Barton of Harvard Business School contributed significantly to the development of the theory of knowledge management and the growth of its practice by examining in their various works and publications the many facets of managing knowledge”. In fact, in 1995, Leonard-Burton documented, via a case study, the effectiveness of the Chaparral Steel Company knowledge management strategy which had been in place since the 1970s.

In the late 1970s, Everett Rogers at Stanford and Thomas Allen at MIT, pioneered studies on information and technology transfer that led to a better understanding of the many facets of organizational knowledge and the usage of computer technology to store this knowledge. One knowledge management system (KMS) that was introduced in 1978 by Doug Engelbert was named Augment, an early hypertext/groupware application system that interfaced with other applications and systems. Another KMS introduced by Rob Acksyn and Don McCraken, in the 1970s and before the world wide web, was called the Knowledge Management System.

The 1980s brought about an increased understanding of the how knowledge served as a competitive organizational asset. However, many organizations had not modified their organizational strategies to incorporate the knowledge concepts and how to effectively manage organizational knowledge. Additionally, theorists like Peter Drucker, Matsuda and Sveiby wrote a lot about the knowledge worker, resulting in the concepts of knowledge acquisition, knowledge engineering, and knowledge-based systems. Furthermore, the building of these concepts resulted in the usages of systems for managing knowledge and publishing of many knowledge management related journal articles.

Knowledge management in the 1990s grew to become a major focus in many local and global companies. Initially, there was not a great deal of interest in knowledge management amongst business executives, however after the publishing of the book by Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi titled The Knowledge Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation, knowledge management was given more attention. In fact, by the mid-1990s, many companies began to realize a competitive edge due to increased company knowledge assets. The end of the 1990s saw the phasing out of the total quality management (TQM) and business process re-engineering initiatives and the implementation of knowledge management solutions.

Current trends in knowledge management

Current trends in knowledge management (KM) are tied to the acceptance of KM for competitive advantage. Knowledge is the key to success and competitive advantage for most organizations. KM is ensuring that the process of distributing and applying knowledge is effectively managed. “Competitive advantage is achieved through developing and implementing both creative and timely business solutions that reuse applicable knowledge and that use newly created knowledge, which is commonly called innovation” 32.

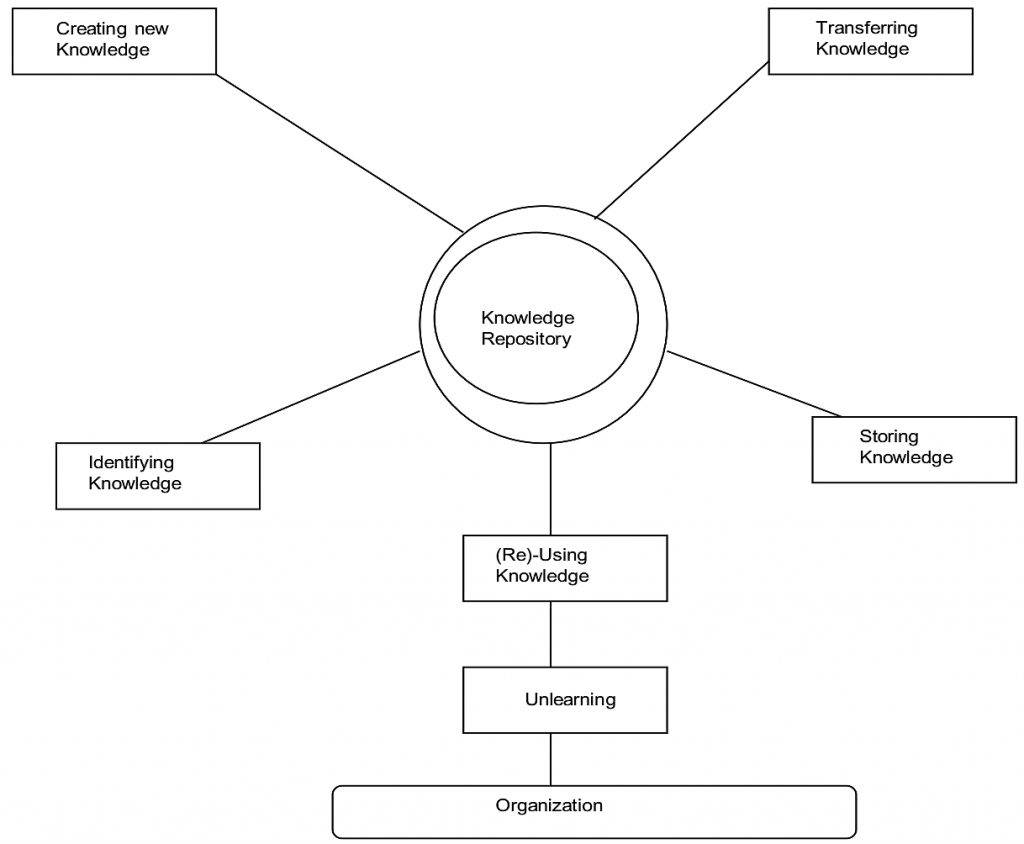

To effectively compete in the current and future economy, organizations must improve their knowledge process efficiency in the knowledge management lifecycle and recognize that its people are the key source of knowledge. The figure below shows the activities involved in the knowledge management lifecycle: identifying -> creating -> transferring -> storing -> re-using -> unlearning knowledge33. First, important and essential knowledge in the organization must be identified. Second, new knowledge must be created by organizational employees and successfully transferred to others in the organization. Third, this information must be stored in a knowledge repository for access by everyone in the organization. Fourth, it‘s key to transfer knowledge back into the organization for reuse by the organization. Fifth, obsolete knowledge must be unlearned to make room for new knowledge 34. The key to this KM life cycle model is that organizations must understand and optimize KM processes to give them a competitive advantage, despite their market segment.

The knowledge production and integration process can be achieved by an organization by promoting sharing among all individuals and inputting gathered knowledge into a knowledge database for access by all. As a result, management will be able to deliver knowledge to the individuals that need it. “With this knowledge, people are empowered to effectively solve problems, make decisions, respond to customer queries, and create new products and services tailored to the needs of clients” 35.

The knowledge management lifecycle. Adapted from Rosemann and Chan36 with permission.

Naming a chief knowledge officer (CKO) has become the latest trend in many organizations. The CKO has the executive responsibility to make the KM process work for the advantage of the company. The complex mission that the CKO must carry out requires that the CKO be very knowledgeable in the KM profession, preferably possessing a PhD.

Included in the CKO‘s responsibilities are37:

- Creating a knowledge management vision

- Integrating knowledge management into the strategic plans of the enterprise

- Selling knowledge management to senior managers and creating a shared vision

- Getting buy-in from competing initiatives and advocates

- Mentoring knowledge management initiative leaders

- Managing multiple projects, vendors, and consultants

- Delivering measurable knowledge management benefits that significantly contributes to the success of the enterprise.

Next edition: Implications of knowledge management.

References:

- Brooking, A. (1999). Corporate memory: Strategies for knowledge management. (Intellectual Capital Series) London, England: International Thomson Business. ↩

- Sunassee, N. N., & Sewry, D. A. (2002). A theoretical framework for knowledge management implementation. Proceedings of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologist, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. ↩

- Pemberton, J. D., & Stonehouse, G. H. (2000). Organisational learning and knowledge assets – an essential partnership. The Learning Organization, 7(7), 184-194. doi:10.1108/09696470010342351 ↩

- Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (2000). Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. ↩

- Dixon, N. M. (2000). Common knowledge: How companies thrive by sharing what they know (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Retrieved from http://web.ebschohost.com.library.capella.edu/ ↩

- Inkpen, A. (1996). Creating knowledge through collaboration. California Management Review, 39(1), 123-140. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7506-7111-8.50015-9 ↩

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company – how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩

- Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal knowledge. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. ↩

- Firestone, J. M. (2000). Knowledge management: A framework for analysis and measurement. White Paper No. 17. Executive Information Systems. Retrieved from http://www.dkms.com/papers/kmfamrev1.pdf ↩

- Neto, R. C. D., & Loureiro, R. S. (2009). Knowledge management in the Brazilian agribusiness industry: A case study at Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira Sugarcane Technology Center). Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(2), 199-296. ↩

- Neto, R. C. D., & Loureiro, R. S. (2009). Knowledge management in the Brazilian agribusiness industry: A case study at Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira Sugarcane Technology Center). Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(2), 199-296. ↩

- Neto, R. C. D., & Loureiro, R. S. (2009). Knowledge management in the Brazilian agribusiness industry: A case study at Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira Sugarcane Technology Center). Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(2), 199-296. ↩

- O’Leary, D. E. (2002). Knowledge management across the enterprise resource planning systems O‘Leary life cycle. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 3(2), 99-110. doi:10.1016/S1467-0895(02)00038-6 ↩

- Ribière, V., Bechina Arntzen, A., & Worasinchai, L. (2007, November 21-23). The influence of trust on the success of codification and personalization km approaches. Paper presented at the 5th International Conference on ICT and Higher Education, Bangkok, Thailand. ↩

- Neto, R. C. D., & Loureiro, R. S. (2009). Knowledge management in the Brazilian agribusiness industry: A case study at Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira Sugarcane Technology Center). Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(2), 199-296. ↩

- Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107-136. doi:10.2307/3250961 ↩

- Becerra-Fernández, I., González, A., & Sabherwal, R. (2004). Knowledge management: Challenges, solutions and technologies. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ↩

- Coleman, V. (1998). Knowledge management at chase Manhattan bank. Paper presented at the Knowledge Management: A New Frontier in Human Resources? London, UK. ↩

- Jennex, M. E., & Olfman, L. (2004). Assessing knowledge management Success/Effectiveness models. 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii. ↩

- Anantatmula, V. (2005). Outcomes of knowledge management initiatives. International Journal of Knowledge Management, 1(2), 50-67. doi:10.4018/jkm.2005040105 ↩

- Gee-Woo, B., Zmud, R. W., Young-Gul, K., & Jae-Nam, L. (2005). Behavioral intention formation knowledge sharing: Examining roles of extrinsic motivators, socialpsychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87-111. ↩

- Ribière, V. (2005). In M. A. Stankosky (Ed.), Building a knowledge-centered culture: A matter of trust (Creating the Discipline of Knowledge Management) Elsevier / Butterworth-Heinemann. ↩

- Chua, A., & Lam, W. (2005a). Knowledge management abandonment: An exploratory examination of root causes. Communications of the Association of Information Systems, 2005(16), 723-743. ↩

- Kaweevisultrakul, T., & Chan, P. (2007). Impact of cultural barriers on knowledge management implementation: Evidence from Thailand. Journal of American Academy of Business, 11(1), 303-309. ↩

- Neto, R. C. D., & Loureiro, R. S. (2009). Knowledge management in the Brazilian agribusiness industry: A case study at Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira Sugarcane Technology Center). Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(2), 199-296. ↩

- Neto, R. C. D., & Loureiro, R. S. (2009). Knowledge management in the Brazilian agribusiness industry: A case study at Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira Sugarcane Technology Center). Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(2), 199-296. ↩

- Neto, R. C. D., & Loureiro, R. S. (2009). Knowledge management in the Brazilian agribusiness industry: A case study at Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira Sugarcane Technology Center). Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(2), 199-296. ↩

- E&Y. Author. (1996). KM international survey. Ernst & Young. ↩

- KMR. Author. (2001). KM review survey reveals the challenges faced by practitioners. Knowledge Management Review, 4(5), 8-9. ↩

- Tuggle, F. D., & Shaw, N. C. (2000, May). The effect of organizational culture on the implementation of knowledge management. Paper presented at the Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Symposium (Flairs), Orlando, FL. ↩

- Uriarte, F. A. (2008). Introduction to knowledge management. Jakarta, Indonesia: ASEAN Foundation. ↩

- The Provider‘s Edge. (2003). The Knowledge Management Advantage. Retrieved from http://www.providersedge.com/kma/ ↩

- Rosemann, M., & Chan, R. (2000, December 31). Structuring and modeling knowledge in the context of enterprise resource planning. Proceedings of the 4th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS 2000), Paper 48. 623-640. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2000/48. ↩

- McGill, M. E., & Slocum, J. W. (1993). Unlearning the organization. Organizational Dynamics, 22(2), 67-79. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(93)90054-5 ↩

- Leitch, J. M., & Rosen, P. W. (2001). Knowledge management, CKO, and CKM: The keys to competitive advantage. The Manchester Review, 6(2&3), 9-13. ↩

- Rosemann, M., & Chan, R. (2000, December 31). Structuring and modeling knowledge in the context of enterprise resource planning. Proceedings of the 4th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS 2000), Paper 48. 623-640. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2000/48. ↩

- Leitch, J. M., & Rosen, P. W. (2001). Knowledge management, CKO, and CKM: The keys to competitive advantage. The Manchester Review, 6(2&3), 9-13. ↩