Conditions proposed by the Department of Justice and Federal Communications Commission would prohibit the combined company from imposing data caps and overage fees on Internet customers, charging large online content providers for network interconnection, and stifling growth of online video by demanding restrictive clauses in contracts with programmers. Time Warner Cable has more aggressively pursued these types of policies than Charter.

Charter doesn't have a sterling reputation, ranking nearly as low as Comcast and TWC in consumer satisfaction rankings. But Charter seized on the differences between itself and TWC while arguing its case and suggested some of the merger conditions that ended up forming the basis of the DOJ's and FCC's final proposals.

While Charter doesn't impose data caps and overage fees on its Internet customers, TWC offers optional plans with limits of 5GB or 30GB a month. The plans ostensibly provide discounts of $5 to $8 a month, but customers who go over the limits can be charged another $25 per month. Charter said it would get rid of these overage fees, pledging that the merged Charter/TWC would not impose any data caps.

TWC was also one of several major Internet service providers to demand network interconnection fees from Netflix. Charter, meanwhile, said it would end TWC's practice of charging the fees to companies like Netflix. A merger condition based on Charter's proposal will guarantee free interconnection for online content providers that "deliver large volumes of Internet traffic to broadband customers," the FCC said.

Cable companies also commonly try to limit the availability of online video by inserting restrictive clauses in cable TV carriage agreements with programmers. Charter has been accused of pursuing these deals, but the DOJ said yesterday that TWC is an "industry leader" in this strategy.

"TWC has been the most aggressive MVPD (multichannel video programming distributor) in the industry in securing Alternative Distribution Means (ADM) clauses in its contracts with programmers that either prevent the programmer from distributing its content to OVDs (online video distributors) or place certain restrictions on such online distribution," the DOJ's announcement yesterday said.

Together, Charter and TWC would have greater incentive and ability to impose or expand these contractual restrictions, the DOJ said. The agency proposes to prohibit the post-merger Charter "from entering into or enforcing any agreement with a programmer that forbids, limits or creates incentives to limit the programmer’s provision of content to one or more OVDs." Charter would also not be allowed to retaliate against programmers that license video to online services.

“Hard to cheer for further consolidation”

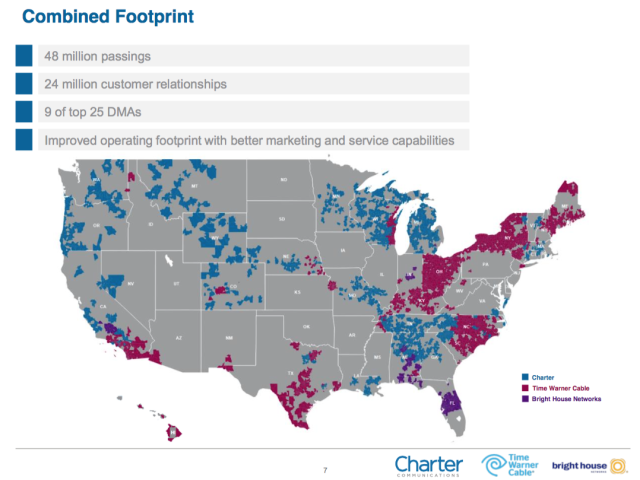

Charter is smaller than TWC but will become the nation's second largest broadband provider after Comcast once it completes this merger and a related deal to buy Bright House Networks.

The DOJ and FCC last year teamed up to prevent Comcast from buying TWC, saying that merger would have given Comcast too much power to stifle the competition that online video streaming services pose to cable TV. In the Charter/TWC case, the DOJ filed a civil antitrust lawsuit to block the merger but simultaneously proposed a settlement that would allow it to proceed with the proposed conditions. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler also proposed that the commission approve the merger with conditions.

Charter wanted the merger conditions to be in force for just three years, but Wheeler is proposing to keep the conditions in place for seven years. Wheeler's statement said the requirements will boost competition in both video and broadband. "If the conditions are approved by my colleagues, an additional two million customer locations will have access to a high-speed connection," Wheeler said. "At least one million of those connections will be in competition with another high-speed broadband provider in the market served, bringing innovation and new choices for consumers, and demonstrate the viability of one broadband provider overbuilding another."

Consumer advocacy groups tried to block the merger but expressed support for the proposed conditions.

“It is hard to cheer for further media and broadband consolidation, regardless of what conditions the FCC or DOJ might adopt," Public Knowledge Senior Staff Attorney John Bergmayer said. "However, there is some solace that, if rigorously enforced, these conditions should eliminate the more egregious harms this merger could cause while creating a baseline for acceptable industry behavior.”

Wheeler said an independent monitor will help ensure compliance.

Disclosure: Bright House is owned by the Advance/Newhouse Partnership, which is part of Advance Publications. Advance Publications owns Condé Nast, which owns Ars Technica. Advance/Newhouse would own 13 percent of Charter after the proposed transactions.

reader comments

65