Reuters, the news and photography agency, has issued an outright ban on photographs captured and submitted in RAW format. Instead, freelance contributors must now only submit photos that were processed and stored as JPEG inside the camera.

According to Reuters, there are two reasons for this move. First, there's the matter of alacrity: RAW images need to be processed by the photographer, which takes time—and when you're reporting on a breaking story, sometimes you don't have time. The second reason is much more contentious: Reuters wants its photographs to closely reflect reality (i.e. be journalistic), and it's concerned that some RAW photos are being processed to the point where they're no longer real.

“As photojournalists working for the world’s largest international multimedia news provider, Reuters Pictures photographers work in line with our Photographer’s Handbook and the Thomson Reuters Trust Principles,” a Reuters spokesperson told PetaPixel. “As eyewitness accounts of events covered by dedicated and responsible journalists, Reuters Pictures must reflect reality. While we aim for photography of the highest aesthetic quality, our goal is not to artistically interpret the news."

Reuters also sent the following note to its freelance photographers:

I’d like to pass on a note of request to our freelance contributors due to a worldwide policy change. In future, please don’t send photos to Reuters that were processed from RAW or CR2 files. If you want to shoot raw images that’s fine, just take JPEGs at the same time. Only send us the photos that were originally JPEGs, with minimal processing (cropping, correcting levels, etc).

It's not entirely surprising that Reuters is banning RAW photos. Over the last few years, one of the most heated discussions in photojournalism circles has been the topic of "how much processing is too much?" Historically, most photojournalists subscribed to the prescribed idea that photos should only undergo minimal processing (minor cropping, correcting levels). The concept was sound: written journalism tries to report the objective truth, and thus so should photojournalism.

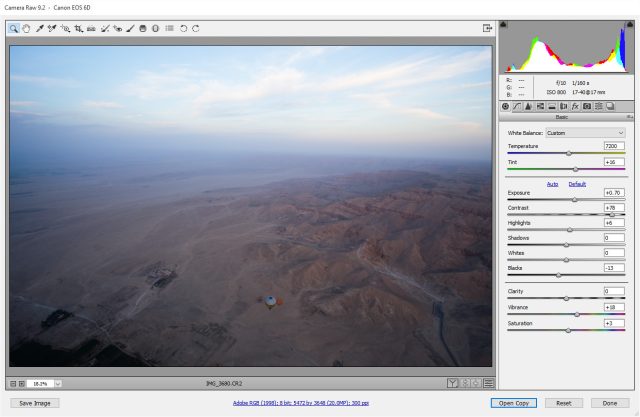

The RAW digital photography format, though, which stores all of the data from the image sensor, allows for very extensive post-processing. Perhaps most importantly, it's possible to make a lot of tweaks to a RAW photo without it looking like an edited photo.

As you can imagine, for an artist, the possibility to change, edit, or improve your photo is rather alluring—so alluring that many photography competitions now require the artist to submit both a finished, processed image, plus the original RAW file, so that they can be compared. For the World Press Photo 2014 competition, a full 20 percent of finalists were disqualified after their processed images were compared to the original, and other competitions have reported similar findings. Obviously, it would be very bad for Reuters if it turned out that 20 percent of its photos were significantly modified.

Banning RAW images completely is one way of handling things, but perhaps a little too heavy-handed. Photojournalists are ambivalent: they generally agree that major changes (removing or adding content to a photo) should be forbidden, but that "minor" changes are okay. The tricky bit is classifying what constitutes a "minor" change. According to an in-depth study (PDF) that polled some 45 industry professionals, there was almost no consensus on what alterations were acceptable. Subjective phrases like "emotional truthfulness" and anachronistic comparisons to wet darkroom methods were often used.

Obviously, it is entirely possible to process a RAW image and only perform minor changes. The problem is, without some rather complex forensic image analysis, it's very difficult to tell just how much processing has been done. Ultimately, that's probably why Reuters took the easy route, even if it'll result in a lot more photos that are blown out, packed full of chromatic aberration, or otherwise gaffes that are very hard to fix in JPEGs.

Listing image by Sebastian Anthony

reader comments

174