The legal industry is moving to adopt GenAI on an enterprise-wide scale, but not all applications are equal, and to adopt GenAI correctly, users need proper training and the right tools for the job

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is set to make waves in the legal profession. As we explored in the first article in this series on GenAI in law, the impactful change coming from GenAI is likely to happen in waves, with the effects cascading from incremental change within the next 1 to 3 years to potentially more disruptive change looking outwards a decade.

The first step towards that change is already happening now: initial adoption. While 85% of legal industry respondents believe GenAI can be used for legal work, this adoption is happening cautiously, according to the recent Generative AI in Professional Services Report from the Thomson Reuters Institute. About one-quarter of law firm and corporate legal department respondents have used public GenAI tools such as ChatGPT. While industry-specific GenAI tools have been slower to come to the market, more than half of legal respondents anticipate using them within the next three years.

As part of charting the future of GenAI, we have been talking to Thomson Reuters’s technology and product experts, including members of TR Labs, as well as a range of experts across industry and academia. Those conversations have underlined factors that firms should be considering as they deploy GenAI across their practices.

As part of charting the future of GenAI, we have been talking to Thomson Reuters’s technology and product experts, including members of TR Labs, as well as a range of experts across industry and academia. Those conversations have underlined factors that firms should be considering as they deploy GenAI across their practices.

Training users on getting the most out of GenAI tools

In Fall 2023, Harvard Business School and the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) conducted a study titled Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier, in which researchers tracked 18 standard consulting tasks with more than 700 BCG consultants, some of whom were given GenAI to help with the tasks and a subset also received prompt engineering training. The control group completed tasks using traditional methods. On average, the study found, those who used GenAI completed on average 12.2% more tasks, 25.1% more quickly and with better quality answers. Those who received training saw a 42.5% improvement in scores versus the control group. Even the group without training saw a 38% improvement.

The study’s authors highlighted two categories of AI users who performed better than others in the test cohort: “centaurs” who systematically divided tasks into those more suited to AI and those that were better completed by humans; and “cyborgs” who constantly interacted with AI and integrated it seamlessly into each task.

However, productivity gains were not universal. The study also found that consultants who used GenAI for tasks to which the technology is not suited (e.g. quantitative data analysis and generating accurate and actionable strategic recommendations) were 19% less likely to produce correct solutions compared to the control group.

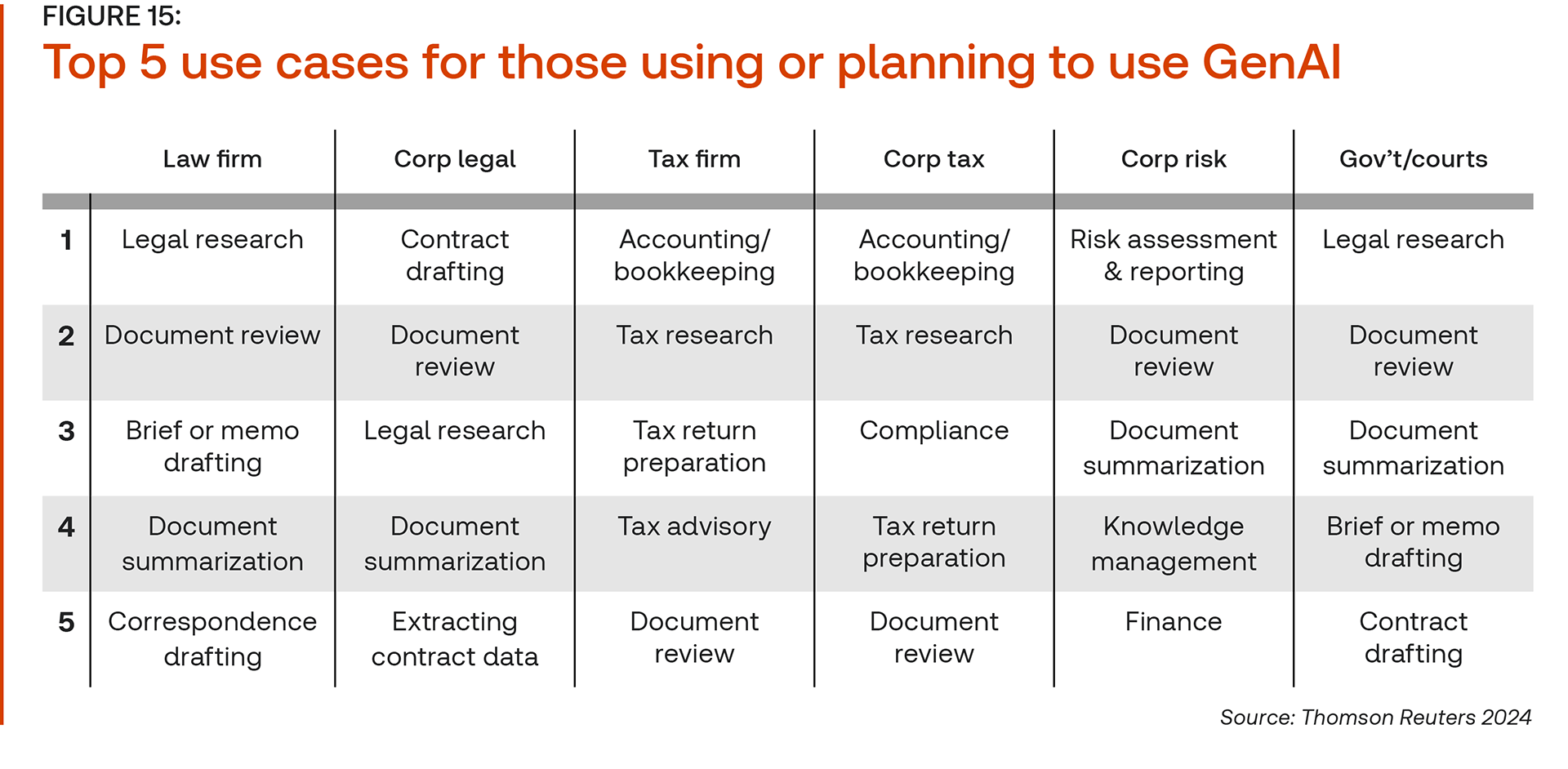

Therefore, it’s crucial to factor in which parts of the legal workflow are more amenable to automation. Some tasks, such as content generation or summarization, lend themselves naturally to GenAI applications, while others, especially those that require more complex or higher-level reasoning, are better handled by humans.

“It’s like having a dictionary and being able to look how to spell all these words, and then complaining that the dictionary isn’t very effective as a fly swatter. Well, it can do that, but that’s not really its role,” says Gabriel Teninbaum, Assistant Dean of Innovation, Strategic Initiatives and Distance Education at Suffolk University Law School, adding that the same challenge comes up with large-language models (LLMs). “I think because of their design, because they’re so easy and intuitive to use, people have this idea that it’s an information machine that knows no limits. The reality is, it has some things that it can do well, and it has some things that it can’t do well at all.”

Picking the right tool for the job

Data privacy & security is paramount — When asked what is keeping them from adopting GenAI, many legal practitioners point to the data. In fact, 68% of legal industry respondents to the Gen AI in Professional Services Report pointed to data security concerns as a barrier to adoption, while 62% said the same of privacy and confidentiality. Particularly given the confidential and sensitive nature of legal work, clients need to be assured that their data is not being used by GenAI tools in unforeseen ways.

This underlines an important difference between most generic GenAI tools and legal-specific solutions. For instance, ChatGPT requires users to opt-out if they wish for their content not to be used to train OpenAI models. Legal-specific tools, however, are often architected with privacy and security at the fore – although firms should check, because even legal products vary.

Answer accuracy & fighting hallucinations — Once privacy and security of data is accounted for, GenAI users need to ensure that the answers generated are correct. Over the past 12 months, stories have come to light demonstrating how things can go wrong when AI tools like ChatGPT hallucinate fictitious case law. Even when an answer is not hallucinated, an answer may not be 100% accurate if the questions posed are interpreted incorrectly by the LLM or are incomplete. Some courts have responded to cases of fake citations appearing in legal briefs by issuing cautionary guidance about relying too heavily on AI-generated output.

There is an important distinction to draw though between generic tools such as ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot and products that have been specifically developed for lawyers. The former draw information from across the internet and are not trained specifically to deal with legal questions. Moreover, they are not grounded in authoritative and up-to-date legal content, and they tend to make things up when they don’t know the answer.

“I think because of their design, because they’re so easy and intuitive to use, people have this idea that [GenAI] is an information machine that knows no limits. The reality is, it has some things that it can do well, and it has some things that it can’t do well at all.”

“I think because of their design, because they’re so easy and intuitive to use, people have this idea that [GenAI] is an information machine that knows no limits. The reality is, it has some things that it can do well, and it has some things that it can’t do well at all.”

— Gabriel Teninbaum

Conversely, it is possible to significantly improve output using legal-specific solutions. For example, retrieval augmented generation (RAG) is a technique that can be used to enhance the accuracy, relevance, and depth of an AI’s answers by essentially giving it access to a verified reference library. In the context of a legal query, giving an AI access to case law, legislation and authoritative secondary source material can help to ensure that the answers generated are tailored to the legal context of the query.

“We found if we could find the right content to give it context within the prompt, it was right almost 100% of the time,” said Joel Hron, the head of TR Labs. “The problem is much more about interpreting the question and finding the right resources that the model needs to answer the question.”

Importantly, the best tools are guard-railed so that the AI tells you when it does not have an answer to your question.

Humans in the loop — Despite technology advancements, it remains critical for human checks to be built into every legal workflow, as ultimate responsibility for client care cannot be delegated to an AI. Lawyers should aim not to reproduce the work that GenAI performs, but instead find ways to provide value on top of GenAI’s output, leveraging their own specialist knowledge.

Wendy Butler Curtis, Chief Innovation Officer at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe says using GenAI is like having “a wonderful over-eager intern or a great first-year associate” doing the work. “You’re going to get a first draft, not in eight hours from that person, but in minutes,” she says. “But the problem is, you don’t know where it’s going, where it’s right, and where it’s wrong.”

As a result, she noted that the tasks where she likes to use GenAI are the ones where the wealth of human experience can have the most impact. “If you’re doing a deposition outline for me in a deposition that I’ve done 100 times, it’s great from moment-go because I don’t have to think to verify it. I can say, ‘That’s good, that’s wrong, it’s missing these three things.’ But if it is not something that I know inside and out, now I have to figure out, how do I verify it?”

Embracing a hybrid future

GenAI is becoming more accessible to legal professionals every day, with applications being baked into work processes spanning from litigation to transactional work. As this occurs, more and more legal professionals will need to move from the conceptual questions around how GenAI will impact their work into the more practical questions of how to use it today.

Responsible and ethical GenAI usage is possible, but while those who do not adopt GenAI may risk being left behind, those who use GenAI without care also risk over-relying on the technology for tasks it may not be suited to perform, leading to less accurate and less efficient outcomes. The true winners of GenAI will be those who pick the right tools for the right jobs and take the time to understand which tasks suit GenAI well, and then supplement those tasks with accurate and strategic legal reasoning.

In coming weeks, this series, Generative AI in the Legal Industry, from the Thomson Reuters strategy team and the Thomson Reuters Institute will continue to explore the practical impact that GenAI is likely to have on legal professionals working in law firms or in-house.