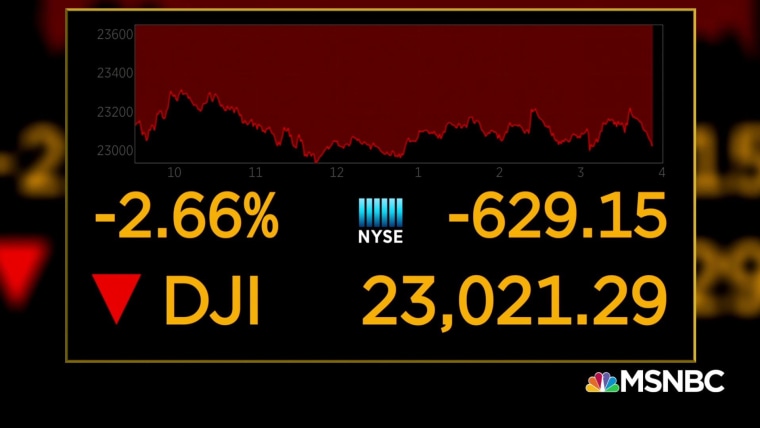

The prospect of cheaper gas at a time when most Americans are holed up at home is not much of a silver lining to the coronavirus pandemic. Energy analysts say there is little upside to the unprecedented plunge in oil prices that sent crude oil futures spiraling into negative territory on Monday, spooking Wall Street.

Patrick DeHaan, head of petroleum analysis at GasBuddy, predicted that the national average gas price could drop below $1.50 a gallon in the coming weeks, noting that a few states have already hit this benchmark. But he said drivers shouldn’t expect to see gas fall as sharply as crude prices. “Unfortunately for motorists, it may not fully make it to the pump, given that stations are trying to keep the doors open — even with volume down 50 to 70 percent,” he said.

Analysts also note that the concept of “negative oil,” as President Donald Trump referred to it in a news briefing on Monday, is more theoretical than actual. Although it suggests that a seller would have to pay a buyer to physically take a shipment of oil, it is largely a “paper transaction” by the financial instruments that hold oil futures contracts.

Paper or not, prices tumbling into negative territory is a symptom of a very real problem: With demand for everything from gasoline to jet fuel plummeting, producers are literally running out of places to store oil once it leaves the ground.

Trump on Monday floated the idea of solving that problem by purchasing roughly 75 million barrels of oil, the spare capacity in the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve, as well as banning imports of Saudi Arabian oil. Neither is likely to be terribly effective, analysts say.

“Refineries are set up to handle specific slates of crude. You can't simply disallow Saudi oil and replace it with American oil,” said Stewart Glickman, energy equity analyst at CFRA Research. Oil has variations in density and sulfur content, and refineries can’t process the kind of oil extracted from American soil.

“Putting a tariff on Saudi crude would do nothing to address the underlying problem,” said Jim Burkhard, vice president and head of oil markets research at IHS Market. “A tariff will not conjure up demand growth.”

“It’s not a terrible idea to fill the SPR with prices where they are, but there is a limit,” Glickman said.

Glickman said American oil producers need prices of at least $20 a barrel just to cover day-to-day operations. For the industry to make money in the longer term, including investing in exploration and equipment, prices need to be roughly double that.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

If prices don’t regain stability, analysts’ biggest fear is that the U.S. energy sector won’t be able to bounce back. “The longer oil remains this low, the more risk there is that when demand rebounds, oil production won’t,” DeHaan said.

Michael Moebs, CEO and economist at financial consulting firm Moebs Services, said plummeting oil prices could drive interest rates — already at historic lows — down even further, a prospect that could have negative implications for banks and destabilize financial markets already shaken by the coronavirus pandemic. “It would be a double-whammy. We see COVID causing a problem… But that’s going to pass,” he said.

By comparison, the hangover from the oil crash could linger well into 2021.

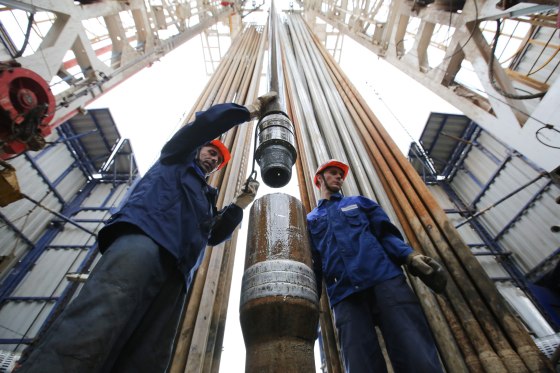

“Oil and gas investment has grown to be a large and important source of U.S. business investment and employment over the past 10 to 15 years, so the decline in prices and falling investment will have a negative impact on the U.S. economy,” Burkhard said.

Although jobs in energy will be the first dominos to fall — especially smaller producers who don’t have the financial cushion to withstand a sustained downturn — they won’t be the last, said Daniel Zhao, senior economist at Glassdoor.

“There also will be spillover effects to businesses that service those industries, everything from car sales to retail spending to real estate," he said.

“It’s not just drilling wells and producers, it's everything that goes downstream… pipelines, refineries, petrochemicals, oil field services,” said Peter McNally, global energy sector lead at investment and research firm Third Bridge.

“There are much broader economic implications this time. It’s not just oil seeing demand drop — it's pretty much every industry,” McNally said.

“Employment in the oil industry is probably going to stay under pressure until we start to see futures prices go above $40 a barrel, and we don’t see that,” Glickman said.

“On a net basis, this is pretty atrocious for the U.S. economy,” he said.