The Great Telework Experiment of 2020 has brought a lot of network challenges to the fore. Obviously some jobs are better suited to remote work than others, and some companies were better prepared to shift in that direction. However, successful telework isn't just about the company infrastructure—it's about employees' home setups, too.

Most of the folks needing to work from home also need to work from Wi-Fi. And Wi-Fi, unfortunately, doesn't scale very well: the more people and devices you cram onto it, the slower and balkier it gets. There are two ways you can alleviate this problem: you can plug your device directly into the router (or a connected switch) with an Ethernet cable, or you can improve your Wi-Fi itself.

Buying a new router is unlikely to substantially improve your Wi-Fi—but if you've got a single router now, upgrading to mesh almost certainly will.

“It’s worse when my roommate is home.”

Last week, an architect confided in me that while the shift to remote work had gone much better for her company than for most of the firms they deal with, they did still have one person coming into the office to work. His home Internet connection just wasn't that great. She added that although he used to be able to work from home, things weren't so great now that his roommate was home all day, too.

The bit about the roommate really got my attention. This was a strong sign that her employee's Internet connection wasn't likely to be the problem at all—it was much more likely to be his Wi-Fi. I asked a few more questions, and she volunteered that the router was in his roommate's room. So, yes—we're talking about Wi-Fi, and we're talking about a shared situation.

You rarely see problems with multiple people sharing an Internet connection, so long as everything's wired—small businesses very frequently share less bandwidth than a single residential connection offers, among ten or more employees, without any complaints. The secret is that businesses—smart ones, at least—have cabled connections to everyone's computer.

When you have two computers with wired Ethernet connections to a router, both computers can talk at once. Each connection is full duplex—meaning the computer can send packets to the router at the same time the router is sending packets to it—so big downloads don't have much of a latency impact on small uploads.

Beyond that, the switch—which connects all the wired connections together and may be built into the router itself—manages all these connections intelligently. This allows the router to get input from each device in a timely fashion, as well as split its own time fairly to deliver requested data to each of those devices.

Wi-Fi is different: it's half duplex, and it's a single collision domain for everyone connected. If your roommate's laptop is sending an email, you can't get the next packet of your Netflix stream until her laptop's done talking—and, similarly, her laptop couldn't begin to send the email until it spotted a break in between your downloading Netflix packets.

Remote work is a lot like online gaming

Simple streaming—watching Netflix or YouTube—is, oddly enough, one of the least demanding tasks you can give your Wi-Fi. The traffic is almost entirely download, and it's not latency-sensitive—if Netflix wants to build up a ten-minute buffer, you'll never know about it; a blip in service will get smoothed out without a single visibly dropped frame.

Unfortunately, while delivering a video stream isn't all that challenging, living on the same network with a video stream can be. If the bandwidth consumed by the stream is close to the bandwidth limit of the Wi-Fi connection (not the internet connection!) there won't be many "breaks" in the stream for your own device to get a word in edgewise.

The key vocabulary word here is airtime. If the majority of the available airtime is already being consumed, a device that has a latency-sensitive communications need—like remote-controlling an office computer—is going to have a bad time.

The spotty airtime availability for your device to upload a request—whether it be a simple HTTPS request to fetch a webpage, or mouse or keyboard inputs delivered to a remote-controlled PC at the office—means things get laggy. You're not having a throughput problem, you're having a latency problem—you move your mouse and click on something, and it takes half a second (or more!) before anything happens.

Congratulations, you're an honorary gamer now—and you have the same complaints they do. You've got the dreaded "lag," and it's breaking your workflow.

A single bad connection is everybody’s problem

Let's go back to our earlier example of a Netflix stream. If one roommate is watching a 4K show on Netflix, that show will eat up—on average—about 25Mbps. In a house with a 100Mbps cable Internet connection, that doesn't seem so bad.

But the same situation can start looking a lot more grim inside the house or apartment itself, when looking at the Wi-Fi. If the router and the streaming device are in the same room, and they're connected on 5GHz, that 25Mbps stream is probably only consuming 15 percent of the airtime. But if they're two rooms apart from one another, the same stream is likely consuming 75-90 percent of the airtime.

Although 2.4GHz connections can carry farther, they're slower to begin with. They also have even worse congestion problems—that same higher range and penetration means you're more likely to have your own devices competing with your neighbors' for airtime on the same frequency. (No, it doesn't matter if you have different passwords—airtime is airtime, period.)

This is when you start having serious latency issues—with the majority of the Wi-Fi airtime already occupied, there are significant delays between when you tell your own phone or laptop you want to request data, and your phone or laptop can relay that request to the router.

The first step is eliminating as many Wi-Fi connections as you can. If your Roku or smart TV is sitting right next to the router—plug it in! Now you don't have to worry about that 25Mbps 4K video stream clogging up your Wi-Fi, and the laptop that does need to be on the Wi-Fi will have a better time of it.

Decreasing airtime consumption with Wi-Fi mesh

For the devices you can't plug in, the next step is increasing their connection quality—again, not just one device's connection quality, all devices' connection quality. Mesh Wi-Fi can help significantly here by cutting down the distance and obstructions needed for each connection.

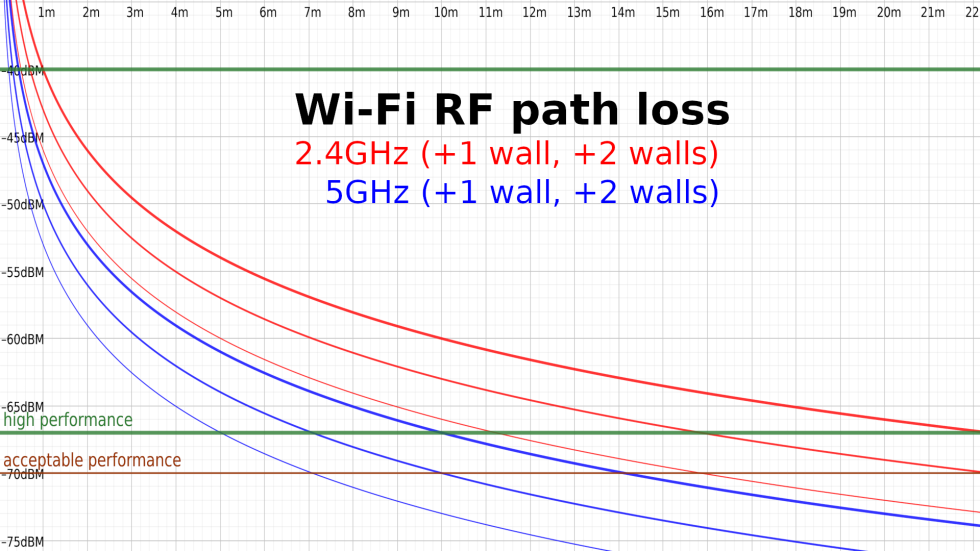

To get the highest connection quality—which means the highest modulation rate, the lowest error rate, and the least airtime used per MiB of data—you need nearby access points. In the graph above, we can see generic RF loss curves at 2.4GHz and 5GHz. Anything above -67dBM should be a solid connection—which means for the 5GHz connections you want, you need to be no more than a room and a wall away.

If you have devices farther from the nearest access point than that, they will have to negotiate a lower QAM rate and tolerate higher error and rebroadcast rates. A device that's 15 feet and a single wall away from the router may be able to move 200Mbps of data, where the same device at 20 feet and two walls is lucky to move 30Mbps.

Where mesh can help here is by shortening the links between devices. Even in the worst-case scenario—where the mesh kit must re-broadcast data on the same channel it receives it—this can end up conserving airtime significantly. And in many cases, the mesh kit can do better than that by communicating with your device and its upstream node on two separate channels simultaneously.

Let's return to the example in which a device is 20 feet and two walls away from a router. This is a pretty iffy connection—perhaps a speed test shows the device receiving 30Mbps of data. Remember, the speed test consumes all available airtime—so while this device should be able to consume a 25Mbps video stream, in doing so, it will have consumed roughly 85 percent of the available airtime.

What if we replace the router with a mesh Wi-Fi kit? Now our device communicates to a mesh node 10 feet and one wall away, and that node communicates with the router node, another 10 feet and one wall away. Even in the worst case—in which all traffic both upstream and down must go over the same channel—we've increased our available airtime significantly.

Since each link of our mesh Wi-Fi connection—the one from your device to the first node, and then from that node to the next—is close by and high quality, they'll be capable of 200Mbps or more apiece. So although we've doubled the total amount of data in flight—our 30Mbps became 60Mbps, since it has to be transmitted twice—it's now only consuming 30 percent of the airtime, instead of 85 percent.

reader comments

267