After the « LuxLeaks » in 2014, the « Panama Papers » in 2016 and the « Paradise Papers » in 2017, the revelations of the « Pandora Papers », resulting from a new leak of 12 million documents from offshore finance, show the extent to which the wealthiest continue to evade taxes. Contrary to what is sometimes claimed, there is no reliable indicator that the situation has improved over the last ten years.

Before the summer, ProPublica revealed that US billionaires pay almost no taxes compared to their wealth and what the rest of the population pays. According to Challenges, the top 500 French fortunes jumped from 210 billion euros in 2010 to more than 730 billion in 2020 (i.e. from 10% of GDP to 30% of GDP), and everything suggests that the taxes paid by these large fortunes (quite simple information, but which the public authorities still refuse to publish) were extremely low. Should we just wait for the next leaks, or is it not time for the media and citizens to formulate a platform for action and put pressure on governments to address the issue in a systemic way?

The basic problem is that at the beginning of the 21st century we continue to register and tax assets solely on the basis of real estate, using the methods and cadastres established at the beginning of the 19th century. If we do not provide ourselves with the means to change this state of affairs, then the scandals will continue, with the risk of a slow disintegration of our social and fiscal pact and the inexorable rise of every man for himself.

The important point is that registration and taxation of property have always been closely linked historically. Firstly, because registering one’s property provides the owner with an advantage (that of benefiting from the protection of the legal system), and secondly, because only minimal taxation can make registration truly compulsory and systematic.

Moreover, the ownership of assets is also an indicator of the taxpaying capacity of individuals, which explains why the taxation of assets has always played a central role in modern tax systems, in addition to the taxation of the income stream (which can sometimes be manipulated downwards, especially for very rich asset holders, as Pro Publica has shown).

By setting up a centralised register for all real estate assets, both housing and business property (farmland, shops, factories, etc.), the French Revolution also instituted at the same a system of taxation based on asset transactions (transfer duties, still in force today) and above all on asset ownership (with the taxe foncière). In France, as in the United States and in almost all rich countries, the taxe foncière or its Anglo-Saxon equivalent, the property tax, continues to represent the main tax on wealth (around 2% of GDP, approximately 40 billion euros in annual revenue in France). Conversely, the absence of such a system for registering and taxing housing and business assets explains the hypertrophy of the informal sector in many countries of the South and the subsequent difficulties in implementing income taxation.

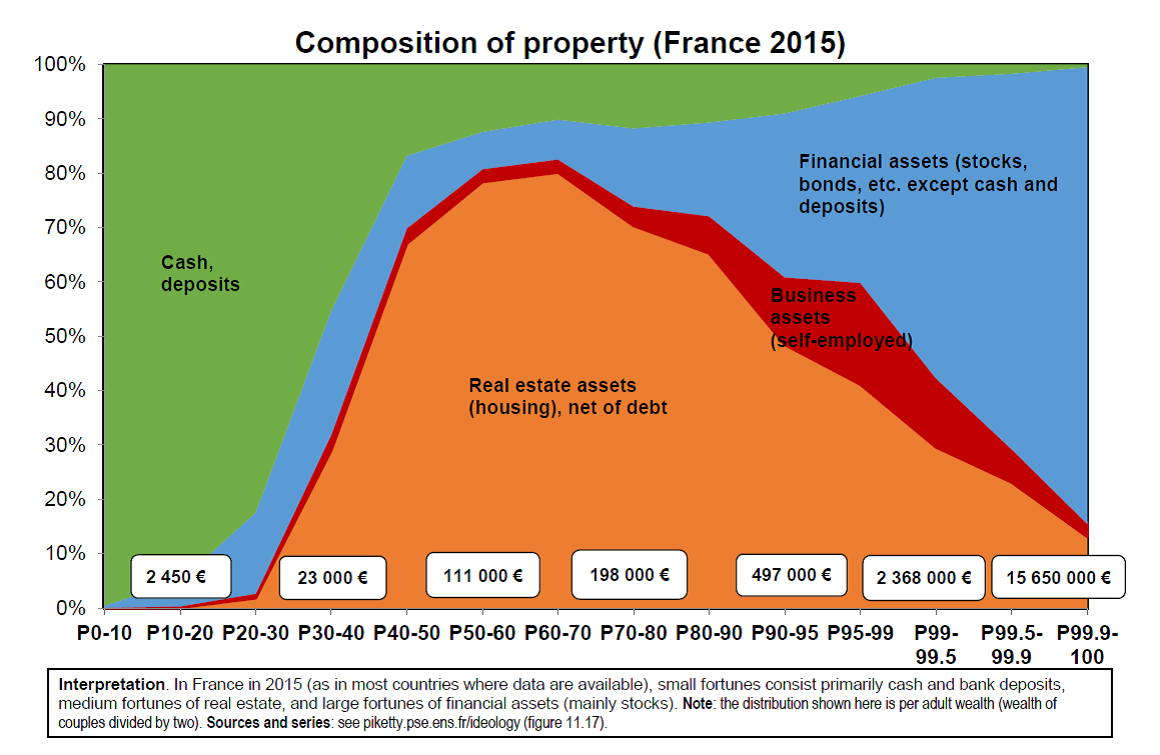

The problem is that this system of registration and taxation of assets has hardly changed for two centuries, even though financial assets have become increasingly important. The result is an extremely unfair and unequal system. If you own a house or a business asset worth 300,000 euros, and you are in debt to the tune of 290,000 euros, then you will pay the same taxe foncière or property tax as someone who has inherited the same property and also has a financial portfolio of 3 million euros.

No principle, no economic reasoning can justify such a violently regressive tax system (small assets holders de facto pay a structurally higher effective rate than larger ones), apart from the fact that it is assumed that it would be impossible to register financial assets. However, this is not a technical impossibility but a political choice: the choice was made to privatise the registration of financial securities (with central depositories under private law, such as Clearstream or Eurostream) and then to introduce the free movement of capital guaranteed by the States, without any prior tax coordination.

The « Pandora Papers » also remind us that the wealthiest people manage to avoid taxes on their real estate assets by transforming it into financial securities domiciled offshore, as shown by the case of the Blair family and their 7 million Euro house in London (400,000 Euros in transfer duties avoided) or that of the villas held on the Côte d’Azur via shell companies by the Czech Prime Minister Babis (who is also suspected of embezzling European funds).

What should be done? The priority should be the establishment of a public financial register and a minimum taxation of all assets, if only to produce objective information about them. Each country can move immediately in this direction, by requiring all companies holding or operating assets on its territory to reveal the identity of their owners and taxing them accordingly, transparently and in the same way as ordinary taxpayers, no more and no less. By abandoning any ambition in terms of fiscal sovereignty and social justice, we only encourage the separatism of the richest and the withdrawal into ourselves. It is high time for action.