Jayla Allen, a third-generation student at the historically Black Prairie View A&M University in Texas, cautioned members of Congress, during a May hearing on the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act in Texas, that a perilous future lies ahead if voter suppression is not curbed soon. “If the recent rise of discriminatory voting laws is not stopped, I fear that more and more people—and particularly young people of color—will become discouraged, disengaged, and shut out of the democratic process,” Allen said.

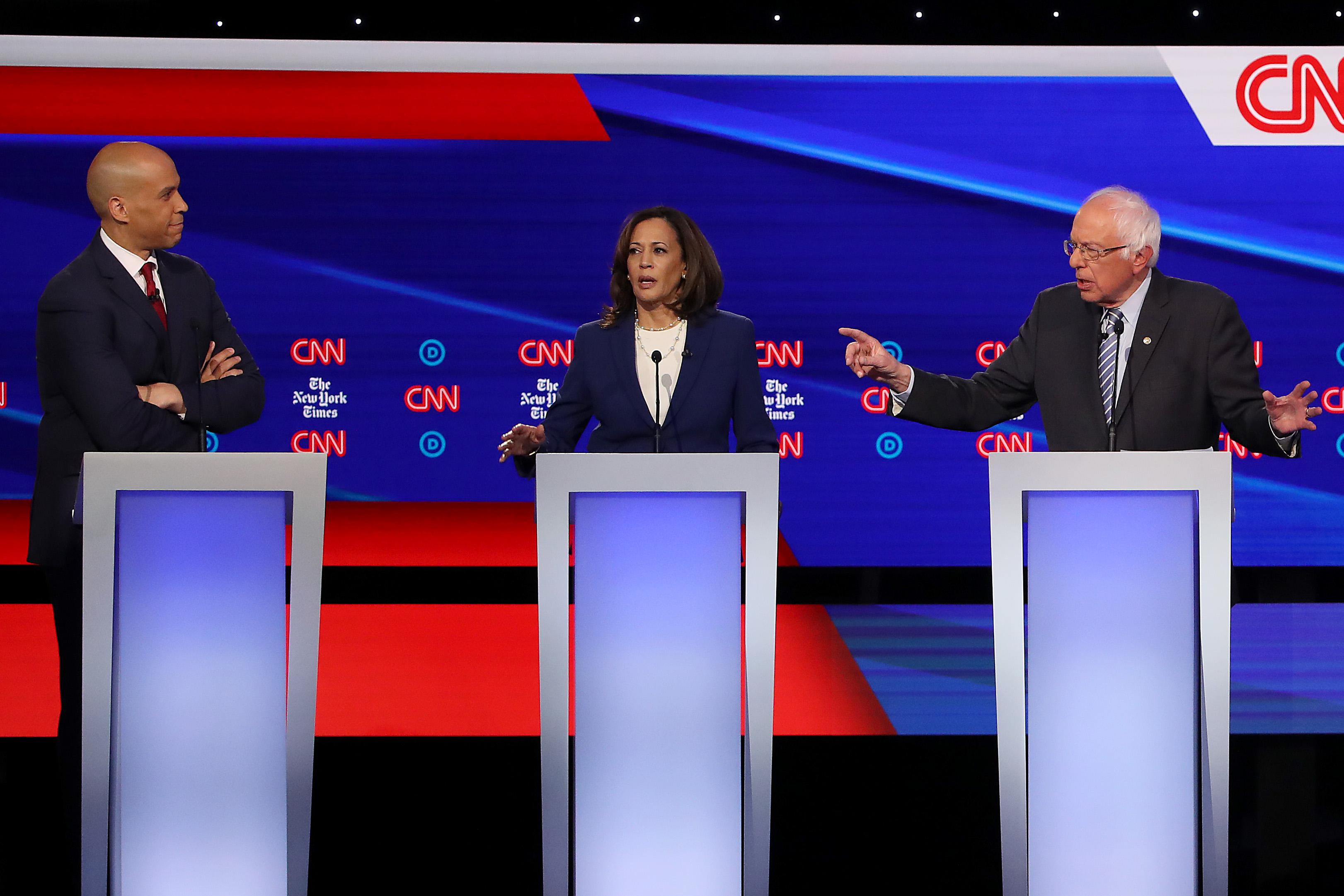

Allen, our client, represents just one of the thousands of individuals who have been affected by increasingly targeted efforts to curtail voting rights in the United States. Black and Latino communities are disproportionately disenfranchised by restrictive election laws. Yet when New York Times readers identified topics they believed were given short shrift in recent debates, voting was glaringly absent from the list. Instead, Social Security, the opioid crisis, affordable housing, women’s issues, and various other topics took precedence. Indeed, voting rights was not a topic presented in any of the 25 presidential debates of the 2016 election, nor in any of the six debates that occurred this year. This totals 31 consecutive presidential debates where there has been virtual silence on voting.

The silence is especially concerning given that this cycle of debates has been hosted by states where voter discrimination has run rampant.

Just this past week, Democratic candidates gathered for a debate in Ohio, the state where lawmakers eliminated the first week of early voting in 2014 and began a massive voter purge scheme in 1994, one that disenfranchises eligible voters for not voting often enough and for failing to respond to single mailings. This scheme eliminated thousands of voters from the rolls. More than 40,000 voters were purged in Cuyahoga County alone, with a population comprised of 40 percent people of color. In 2018, the Supreme Court upheld Ohio’s purging scheme. The state now plans to purge an additional 200,000 voters from the rolls before the 2020 elections, despite the discovery that thousands of names were wrongly flagged. Even in the face of these egregious attacks on voting rights, the silence continued.

The absence of a discussion on voting rights was also striking at a debate held at Texas Southern University, a historically black university. Texas is a hotbed of voter suppression, much of it directed at students at HBCUs. Following the 2018 midterm elections, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (which I am associate director-counsel for) filed a lawsuit on behalf of students at Prairie View A&M University, who were denied early voting opportunities by majority-white Waller County election officials. The county has continuously failed to address systemic problems that make voting more difficult for minority students. As one student reportedly stated: “Us young black people coming in, I don’t feel like we get the same chances. We’re not treated the same. The laws are uneven for us.”

Now, as we look toward the November debate in Georgia, it is similarly impossible not to think of the voter suppression allegations that centered around the high-profile race between now-Gov. Brian Kemp and Stacey Abrams. Just before the 2018 midterms, a report from the Associated Press found that 53,000 voter registrations—70 percent of them from Black voters—were being held by then–Secretary of State Kemp’s office for failing to be “exact matches” of registration information to Social Security and state records. This system implemented by the Georgia Legislature was designed to combat voter fraud, which is virtually nonexistent, and instead blatantly burdens people of color. Last spring, the House Oversight Committee opened an investigation into what occurred in Georgia nearly a year ago and we have yet to get answers.

The widespread voter suppression problems in three debate locations—and the repeated omission of voting rights discussions from presidential debates over the past few years—is startling. The last decade unleashed an onslaught on democratic participation, including stringent voter ID laws, an array of voter registration restrictions, sweeping illegitimate voter purges, an alarming rise in polling place closures, this administration’s blatant attempt to form a federal commission aimed at voter suppression, and foreign interference in our elections that targeted black Americans more than any other group. The preservation and operation of our democracy requires an electorate that is adequately informed about the extent of the threat to voting rights when making choices about who should lead our country.

This reality should inform voters. It is inexcusable that debate organizers and moderators time and again fail to question candidates about voting rights or ask for their plans for national voting reforms if elected president.

Debate watchers should look to the 2018 midterms for warnings of what could happen in 2020. There were significant reported barriers to voting in 2018—particularly in states that were formerly protected by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which the Supreme Court gutted in 2013 in the infamous Shelby County v. Holder decision. Voters in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Texas experienced poll closures, malfunctioning machines, and inaccurate voter rolls, and they waited in lines for up to four hours.

Voters should also know that, leading up to the 2018 elections, there were mass purges of Black and Latino voters in Georgia and Ohio, fraud on Black voters using absentee ballots in North Carolina, and a new and onerous ID requirement imposed on Native American communities in North Dakota. Black and Latino voters are twice as likely to be removed from the voting polls as white voters. They are also three times more likely to face voter suppression or be turned away from the polls.

Despite these clear threats to democracy, the candidates vying for a place on the ballot in the 2020 elections have hardly been asked about these issues during debates. This is despite the fact that all of the 2020 Democratic candidates support the restoration of the Voting Rights Act—and some of them have proposed comprehensive voting and election reforms as part of their campaign platforms.

Elected officials bear the greatest responsibility to ensure equal and unobstructed participation in our democracy as well as the security of our elections. Our representatives must work to end all forms of voter suppression and should be permitted the time and space to propose their solutions for doing so during presidential debates. The omission of voting rights questions from moderators sends the message to Americans that the issue is not worthy of discussion. If candidates were given the opportunity to subject their ideas on voting reform to rigorous questioning during the debates, it would help increase public awareness of these issues. And, crucially, voting rights would become a stronger consideration at the ballot box.

In fact, if voting rights were a featured topic during the debate, Americans would better understand that comprehensive voting reform is both utterly necessary and absolutely possible if it is prioritized by the next administration. There are several simple steps to take toward reform. For example, automatic voter registration would dramatically increase the number of registered voters from 9 percent to 94 percent. Expanded early voting would enable 49 percent more eligible persons to vote. Making polling sites and voting machines accessible would allow people with disabilities (20 percent of the population) to vote more easily. And abolishing the laws that punish our democracy by denying the vote to persons in the criminal legal system would restore the voting rights of 4.5 million American citizens, including the 1.4 million people with criminal convictions who would be enfranchised by Florida’s new law, Amendment 4, were it allowed to operate as voters intended. Some of these reforms are ones that candidates have already suggested in their campaign platforms, though each candidate for the presidency should be asked about them directly in order to distinguish among their differing approaches to the issue.

Whoever is elected president in 2020 has an uphill battle in rebuilding our democracy and restoring faith in our elections. There is no outcome, no fear we can imagine that is worse than the continued debasement of our right to vote. Ultimately every right we enjoy hinges on the right to vote. It is the gateway to change-making and to preserving the ideals we hold most dear. There should be little debate that the right to vote is fundamental, and there should be no presidential debate that does not give the right to vote the platform it deserves.

In fact, it should be one of the first questions at the Georgia debate on Nov. 20: Reports of widespread voter suppression in Georgia made national headlines last year. If elected president, what would you do to address the ever-increasing barriers to the ballot box that voters across the country are facing?