By Dennis Crouch

In re Hodges (Fed. Cir. 2018)

In a split opinion, the Federal Circuit has rejected the PTAB’s anticipation and obviousness decisions – finding that the Board erred in holding that the key prior art reference inherently disclosed the an “inlet seat” defined by a “valve body” of the claimed drain assembly.

Anticipation arises from analysis of the “four corners” of a prior art reference. That one document must “describe every element of the claimed invention, either expressly or inherently, such that a person of ordinary skill in the art could practice the invention without undue experimentation.” Spansion, Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 629 F.3d 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2010). Although “inherent description” offers some leeway, the doctrine only applies if the supposed inherent characteristic necessarily follows from the express teachings of the reference. Right-off-the-bat, we can note a problem here with the Examiner’s statement that “it is at least ‘arguable’ that [the prior art reference] does not disclose “a valve body which defines an inlet seat.”

Beyond that, in walking through the prior art, the Federal Circuit found a major problem with the PTO analysis — basically that the prior art’s “valve body” was disconnected from the inlet-valve (that inherently contained an inlet seat). Thus, according to the court, the valve could not “define” the inlet seat as required by the claim.

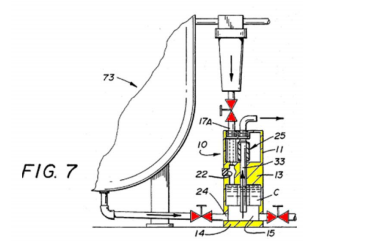

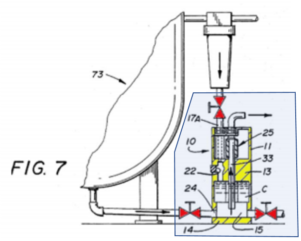

Figure 7 avove from the prior art shows the issue: The portion marked in yellow defines the claimed valve assembly and the top red valve is the location of the required inlet seat. The claim though requires that the valve assembly “define” the valve seat. I’ll note here a major problem with the analysis – why not just define the “valve assembly” of the prior art as including the upper valve (as I’ve done with my redrawing of Figure 7 below)?

I mentioned above the split opinion. Both the majority (Judges O’Malley and Lourie) and the Dissent-in-part (Judge Wallach) agreed that the PTO had failed to show anticipation. The difference came with the result – the majority reversed while the dissent would have taken the lesser action of vacating the PTAB ruling.

Here, the appellate panel’s problem with the PTAB is that it found an erroneous factual finding. However, because the lower tribunal is ordinarily seen as the finder-of-fact, the result of this type of disagreement is usually to vacate the PTAB’s decision and have the lower tribunal review the evidence once again. Here, the Majority justified its reversal with a conclusion that the PTAB conclusions were “plainly contrary to the only permissible factual finding that can be drawn from [the prior art] itself.”

Writing in dissent, Judge Wallach argues:

When an agency fails to make requisite factual findings or to explain its reasoning, “the proper course, except in rare circumstances, is to remand to the agency for additional investigation or explanation. The reviewing court is not generally empowered to conduct a de novo inquiry into the matter being reviewed and to reach its own conclusions based on such an inquiry.” Fla. Power & Light Co. v. Lorion, 470 U.S. 729, 744 (1985). By reversing the PTAB’s determination [of anticipation] the majority engages in the very de novo inquiry against which the Supreme Court has cautioned.

Another precedential case today on a failure to establish facts and evidence by a district court when deciding on 101 at 12(b)(6) stage.

link to cafc.uscourts.gov

Note the attempted brakes by Ryna in the Dissent In Part….

The “fact-based” part threatens the ability to hand wave justice (and the spin from Ryna is rather stark).

The intracircuit split on how to handle 12(b)6 and Alice in general is untenable to maintain. The Supreme Court is going to have to take cert on one or two of these cases- hopefully next term, but it will be a near term.

There is NO “intracircuit split.”

These cases are merely showing the “common law” evolution and realization that the factual component of the 101 inquiry cannot be so easily dismissed.

There is NO panel decision that is in direct opposition to the this current string of cases getting more specific about the factual predicate prong that could even be pretended to provide a “split,” and dissents do not count for such.

Your “untenable to maintain” is merely a misguided reflection of your feelings on the larger topic.

What you DO see in the Dissent In Part is Ryna crabbing that pretty soon ALL “scriviners” will notice the existing flaw in how the courts have been trying to avoid treating all elements of the 101 inquiry properly, and the bandwagon effect will EFFECTIVELY stop the misappropriated mechanisms.

Too bad. So sad.

Of course, this realization will have even more impact outside of the Article III forum. See the recent discussions (and note that I was the very first on these boards to draw attention to the factual predicates of 101), and note full well the following:

1) Establishing “conventional” goes well beyond merely the typical 102/103 “existing as prior art.”

2) Official Notice – per the Office own memorandum (as supported by case law and the APA which governs the NON-Article III examiners) – has strict limitations of how that vehicle is applied. Those strict limitations include the FACT that Official Notice cannot be used to establish a ‘state of the art,’ which is the very thing that IS the factual predicate in the 101 evaluation.

3) the application of the Alice/Mayo “two-step” on ANY fact pattern not already adjudicated has been stated by the CAFC to be an application of common law. The USPTO does NOT have authority to use common law development (either in the PTAB***), and much less so in the examination process.

It is only a matter of time before a SERIOUS challenge – and an innately successful one – arises to shutter the “gift” of the “Gist/Abstract” sword from the Supreme Court (in at least the executive branch administrative agency use of that weapon).

***Note that the attempted revision of Ex Parte Poisson in the more recent PTAB case of Ex Parte Johnson is now clearly – and unequivocally – wrong. See link to patentlyo.com

***Note that the attempted revision of Ex Parte Poisson in the more recent PTAB case of Ex Parte Johnson is now clearly – and unequivocally – wrong. See link to patentlyo.com

Examiners have been complaining about Applicants citing to In Re Poisson…

PTAB was embarrassed it was released and have been trying to claw it back since. My guess is that the Poisson panel is no longer working at PTAB…

That would be humorous, seeing as that panel “got it right” as now being confirmed by actual Article III courts.

The PTAB has no authority to make up its own brand new law.

But watch them try – and then try to deny that’s what they are doing when the ‘ol Oil States Case comes up in discussion….

All three members of the Poisson panel are still at the PTAB.

Some PTAB panels continue to agree that evidence is required to support a finding that a feature is conventional, while many others do not.

For example, in Shioyama, the PTAB found in favor of an applicant based on the fact that “the Examiner has not provided evidence that the abstract idea claim steps are routine and conventional”. Ex Parte Shioyama et al., appeal no. 2016-001637, slip op. at 7 (PTAB October 20, 2017).

An intracircuit “split” is an approximation automatically compared to precedent-creating final judgements of actual seperate circuits. It’s a split because what you get is virtually entirely panel dependent and the chances of anything getting en banc treatment are low.

The flaw with the 12(b)6 and Alice has always been that any attorney waving their hand and saying “what we are doing is not conventional” should, and does, kill the motion.

Markmanprocedure must be expanded to include eligibility and a preliminary patentability review (i.e. what the Alicetest really is) and it will be, sooner or later.

Do not attempt to save your clearly wrong use of the word “split.”

Put

The

Shovel

Down

wrong wrong wrong wrong wrong

the prior panel rule means decisions made by earlier panels are binding on later panels.

it’s quite sad how a non-lawyer bats you around so easily. assuming of course, that you are an actual lawyer. easy to doubt it.

Compare:

the prior panel rule means decisions made by earlier panels are binding on later panels.

it’s quite sad how a non-lawyer bats you around so easily.”

with:

“There is NO “intracircuit split.”

These cases are merely showing the “common law” evolution and realization that the factual component of the 101 inquiry cannot be so easily dismissed.

There is NO panel decision that is in direct opposition to the this current string of cases getting more specific about the factual predicate prong that could even be pretended to provide a “split,” and dissents do not count for such.”

You might want to stop being so eager to pat yourself on the back and try reading what was posted.

I agree with the dissent by Wallach that the only issue that should have been decided was whether the applicant should have been allowed to file and the amended complaint given that it apparently raised factual issues that need to be considered by the court as to whether the claimed invention was directed to an improvement to technology as opposed to simply processing data.

Of course you do.

My very thought. Not surprising that Ned aligns with an anti-patent viewpoint when it comes to 101 matters.

Anon, I agree with you that to the extent that the courts were requiring something a lot more than just novelty in order to obtain a patent under a requirement for “invention,” then they were just wrong. As Federico said, the new section 103 was an attempt to codify the requirement for nonobviousness expressed in Hotchkiss which held that because the suitability for the use of “clay” in doorknobs was known, there was no patentable invention for claiming a clay doorknob. Furthermore, the Supreme Court stated and Graham v. John Deere that the intent of Congress was to codify Hotchkiss and its related cases. It did agree though that the 2nd sentence of 103 “overruled” the dicta in Cuno about flash of genius.

But all that is about novelty. The requirement that an invention disclosed in claim a new or improved manufacture (machine, manufacture, composition or process) is completely distinct from the issue of novelty except when the claimed subject matter mixes new and old in in a stew, particularly if what is not is not otherwise a “manufacture.”

perhaps salvaged….

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

February 13, 2018 at 6:57 pm

You start out talking 103 and end up with the statement of “But all that is about novelty.”

Really?

ALSO – you should be very well aware that Congress choose “obviousness” (not novelty) INSTEAD OF “invention” based on the fact that the Supreme Court had FAILED to come to any meaningful gestation of the term of “invention” even though prior to 1952 Congress has permitted the Court to have a common law power to set that term.

This is well known historical knowledge.

As is the mess that the Court engaged in with “Gist” as in, “Gist of the invention” or any number – large number – of permutations of the term “invention.”

I have shared with you (personally) many times the background to 103 and why what I tell you is fact.

ALL ELSE that you attempt to spin after your misstatement of “that is about novelty” is complete and utter B$.

“Figure 7 avove from the prior art shows the issue: ”

Dennis –

I think you meant: Figure 7 above from the prior art shows the issue:

For $2,800. or less in PTO appeal fees for ex parte application claims [1 day or less of outside attorney fees] you are expecting an Article III level proceeding by the PTAB? With “fact findings on the Graham factors” even though they are rarely even argued, much less fact supported, by most applicants? And with relatively few clients these days even willing to pay for an oral argument opportunity? It’s surprising there aren’t even more rubber stamp decisions of examiner decisions than there already are.

“much less fact supported, by most applicants?”

It is not the responsibility of applicants to support the Graham factors.

You have been away from prosecution for too long, Paul.

And your apparent wanting of more “rubber-stamping” exhibits a fundamental misunderstanding of what is proper.

It is not the responsibility of applicants to support the Graham factors.

Of course it’s the applicants responsibility. LOL

You expect the PTO to do research on the “commercial success” (which is definitely the absolute st 0 0 pidest of the so-called factors) of products falling within the scope of the applicant’s claims? Give everyone a break.

Don’t be obtuse Malcolm.

Of course the secondary factors aspect has aspects that need to be tended to by the applicant.

But that certainly was not the thrust or context of the conversation.

I am talking about the prima facie case – try reading the comments here in context. NO ONE is talking about those items that may be raised in rebuttal and it is beyond obvious that THOSE items in rebuttal would be provided by the applicant.

Graham factors are mostly nonsense anyway.

Also judge made nonsense for the benefit of applicants but of course that sort of “activism” will go ignored by the usual hypocrites who habitually screech about such things.

Your anti-patent bias is evident in your feelings here.

Get into a line of work in which you can believe in the product you supposedly deliver to your “clients.”

anti-patent bias

Big difference between “anti-patent” and “anti-cr@p baseless pulled-out-of-the-behind” “factors”.

But again: it’s impossible for you to understand any of this. You’re “all in”, as they say. You live to spread your mythology about the awesomeness of patents and the ign0rance of any who would dare stand in the way of grant. That’s why you’re here.

I’m here to point out that people like you exist. People might not believe that there’s such things as a glibertarians who run around crying about “political correctness” and “freederm” while simultaneously p ssing themselves because they can’t own enough patents that protect facts and logic. We don’t have to “make you up.” There’s not many of you but, dang, what a bunch of screaming entitled babies. It’s absurd.

You “say” impossible for me to understand all the while all you merely do is spout your feelings with NO provision of how those feelings are actually connected to the law.

Your deflection is noted (but thanks for trying to move the goalposts and make this about “my” understanding.

Keep on “shining that light” as your legend in your own mind status continues to blossom from that massive amount of fertilizer there.

Point well taken Paul.

Ideally, though, shouldn’t the requisite fact finding to support an examiner’s rejection be done by the examiner during examination, not by a PTAB panel during review of the examiner’s action? I am in agreement that the Graham factors are rarely made an issue during examination, but it doesn’t seem like that should mean that an applicant can’t make them an issue.

(As an aside, with respect to the cost of a PTAB proceeding, you can get an article III level proceeding by the Fed. Cir. for $500 in appeal fees. It has always struck me as odd that the appeal fee to the Fed. Cir. is less than the appeal fee to the PTAB.)

[T]he Graham factors are rarely made an issue during examination…

This is surely true, but passing strange. I agree that the examiner corps rarely makes explicit Graham findings (although, ironically enough, they nearly all cut and paste the language that says that they have to make such findings). I also agree that few applicants ever press back on this point.

It is the lack of argument on this point from applicants, however, that really surprises me. As I said above, I really do not understand how one can possibly assert obviousness without a firm understanding of who is the person of ordinary skill. After all, §103 prohibits patents not merely when the invention is “obvious,” but when it is “obvious… to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains” (emphasis added). In other words, it is not enough that it be obvious to someone. It must be obvious to a very specific person, and this specific person is 100% fictional. Until you can nail down some specifics about the fictional composite, it is logically impossible to assert a conclusion of obviousness. And yet, it happens day in and day out that assertions of obviousness are advanced without a word having been said about this legal fiction, except that idea [X] was supposedly obvious to this fiction’s intuitions. Why do so few of us press back against that assertion, when it is so palpably lacking in logical foundation until and unless some meat is hung on the fiction’s bones?

Yet another reason I advocate constantly for an expanded Markman procedure to construe the invention- not just the words in the claim- as a matter of law. The meaning of the words do not (cannot) automatically create the meaning of the invention.

Without knowing exactly what the invention legally is, how can the legal fiction of PHOSITA be sustained?

The patent law provides that the applicant must fully and clearly describe that which they consider to be the invention- it seems impossibly out of balance that any form of litigation could proceed without adversarial legal construction of that same invention.

[C]onstrue the invention- not just the words in the claim- as a matter of law…

I am afraid that I do not quite understand what you are trying to say here, Martin. What is the difference between “the invention” and the “the words in the claim”? To my mind, these are the same thing.

“The invention” whose obviousness is being assessed is whatever is encompassed by the words in the claim. I agree that up-front Markman procedures are efficient, and I agree that we cannot determine the characteristics of the PHOSITA without knowing what invention is claimed, but I cannot understand how one might construe “the invention” apart from construing the “words of the claim.”

Greg “what the invention is” can be very a separate meaning from the words themselves.

Almost any computer-implemented invention may be characterized as an improved computer, or an improved {insert computerized function here} ….that’s most of the battle in 12(b)6 motions under the Alice regime.

Do I have claims to an improved computer (PHOSITA are computer engineers) or an improved stock trading device (PHOSITA are stock traders) or an improved User Interface (PHOSITA are GUI designers)?

I am still not following. How do we determine whether the patentee is claiming an improved computer or an improved method of doing [X] by using a computer, except by construing the words that the patentee uses to claim the invention?

Tell me Martin, who did congress authorize as the entity that gets to decide “what the invention is?”

(112 is not only a requirement, but it is an authorization as well)

Tell me anon, who does the Constitution vest with the judicial power to enforce or void statutes and laws when scope or constitutionality are questioned?

The asymmetry of the applicant’s definition not being questionable in an adversarial, constitutional system of justice is not sustainable.

More salvaging from the “don’t have a dialogue” count filter…

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

February 13, 2018 at 9:17 pm

“Tell me anon, who does the Constitution vest with the judicial power to enforce or void statutes and laws when scope or constitutionality are questioned?”

Note explicitly that you do not ask about re-writing the statutory law that is patent law.

I have NO problem with “void or enforce” – you have not been paying attention.

AND

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

February 13, 2018 at 9:18 pm

“The asymmetry of the applicant’s definition not being questionable in an adversarial, constitutional system of justice is not sustainable.”

Your feelings are noted – as is your lack of any real knowledge of law.

+++

So, let’s return to the discussion, eh Marty? You will note that I have never been against the proper application of the judicial power that is vested in the judicial branch, just as you will note that your reply to that thrust DOES NOT ANSWER my question put to you.

Are you done attempting to move the goal posts (to a point that does not even support your contentions concerning the topic of this discussion?

Would you care to continue the discussion and answer the question that I put to you?

Or are you too busy >already trying to pat yourself on the back?

Graham factors… are rarely even argued, much less fact supported, by most applicants.

This is, no doubt, true, but does that not strike you as strange? There are a number of interlocutors around these parts that are very eager to contend that it is a scandal how flagrantly the CAFC (and before them the CCPA) ignores the SCotUS’ directives on §101. Somehow, however, the SCotUS’ lead case on §103 is ignored entirely, and no one bats an eye.

Why, it is almost as if all the high-minded folderol about respect for the rule of law that one hears from the partisans of a more aggressive eligibility standard is really just a cover for grubby self-interest…

Greg are you talking about KSR? If so, I could not agree more.

You presuppose that the applicant CAN in fact persevere until the incorrect rejections no longer occur.

In the real world, applicants are in fact “worn out.”

It costs nothing for the Office to make such errors, while it costs the applicants all the fees (and time) to refute those errors.

So while you indeed have a point on the asymmetry involved between Type I error (bad rejection) and Type II error (bad allowance), you omit – or plain misstate – important elements of those types of errors.

And let me repeat (since you may be relatively new here), ANY type of rubber stamping is bad.

Rubber stamping “Reject Reject Reject” is bad.

Rubber stamping “Accept, Accept, Accept” is bad.

Diligent examination – with proper evidence and application of law – is the only proper path forward. And even though Malcolm whines otherwise, THAT proper examination is what the PRO-patent people (what Malcolm attempts to denigrate as “patent maximalists”) want.

Oddly, the comment to which this post is a reply to no longer exists.

There appears to be more “instability” in the software. I have to wonder if more “ecosystem improvements” are being experimented with.

The public interest in preventing and eliminating junk patents is paramount.

Never forget it.

“The public interest in preventing and eliminating junk patents is paramount.

Never forget it.”

Paramount: /ˈperəˌmount/

adjective:

more important than anything else; supreme.

You need to get into a different line of work.

You are NOT placing your supposed client’s interests as a priority with your self-appointed guardian of the fields of (patent) rye job.

Your feelings over “junk” have over ridden any sense of reason in you.

The public’s interest is superior to an inventor’s interest by sheer dint of numbers/utilitarianism, or any reasonable philosophy of a commonwealth.

Does this even need to be explained?

The public is composed of individuals. There is no such thing as “the public’s interest,” separate from a summation of individual interests. Given that each individual has an interest in his or her property rights being respected, the “public’s” interest is likewise served by due regard for individual property rights.

Naturally, however, I agree that where there is no real property interest, but merely an illusory assertion of property (as where one has claimed unpatentable subject matter), then the public’s (just like the individuals’) interest lies in acknowledging that the asserted right is merely illusory.

Only a person who is anti-patent so dismissively forgets that those innovating ARE doing so “in the public’s interest.”

That is why we have a patent system in the first place.

Perhaps you confuse the Efficient Infringer as being the only part of the public that you want to be concerned with…

Given the fact that your own personal feelings have been tainted, your view is hardly the objective rational one, now is it?

“Only a person who is anti-patent so dismissively forgets that those innovating ARE doing so “in the public’s interest.””

Not technically true for the “public” of muh victims. Those particular “public” are simply oppressed every time an invention is made/disclosed, though they might at some point down the line benefit some small bit. Just ask MM. He an run you through how that works.

LOL, 6.

But we both know that that “logic” actually proves the point, eh?

The peanut gallery really wound up today! Lol.

Thank goodness applicants never “take a mile” when given an inch.

Note also the CAFC here stretching the law to help the applicant. Where’s the screeching about “separation of powers” from the usual suspects? Suddenly it got quiet. Shocking! Lol

Where is this supposed “stretching”…? What is the separation of powers issue that you want to allude to?

Speak directly please.

See the dissent.

“See the dissent”

I saw the dissent. A comment I submitted (in reply to Jonathan) addressed the many faults of that dissent. Unfortunately, the system today is evidently experiencing a withdrawal of pizza for the college students at the local coffee shop, and that comment has been lost.

Bottom line though is that Wallach shows a rather poor appreciation of the patent system, what 35 USC 102 stands for, and for the fact of the matter that the majority HAS the support (in at least the admission of the examiner) for the PARTIAL reversal of the (binary) anticipation issue. Wallach’s comment in relation to somehow a “tie” going to the Office is reprehensible in and of itself.

Maybe you should apply some critical thinking to that dissent instead of merely “seeing it.”

There is no stretching of the law. The majority does nothing except reverse a rejection that even the dissent acknowledges was incorrect. The rule that the USPTO has the burden of proof and reversal is appropriate if the USPTO fails to meet its burden has been in place for decades. J. Wallach is the one that wants to change the law.

And there is no help to the applicant. The applicant is back at square one and subject to any other rejection that the examiner decides to make.

My favorite line in this opinion came at slip op. pg. 15:

This is a pet peeve of mine, the PTO’s failure to make fact findings on the Graham factors. I really do not know how it is even possible to reach a conclusion of obviousness unless one first identifies the level of skill of the notional person of ordinary skill, and yet north of 50% of the rejections that I read have nothing to say about who the person of ordinary skill is and how much education/experience this person has. District court opinions routinely make an explicit finding on this point after the two sides put a fair effort into debating it, but this point is routinely ignored entirely by the PTO.

Ignoring this fact finding, however, is reversible error, as per Hodges. I am going to be cutting and pasting this quote into a lot of appeal briefs.

Whoops, I should have noted that the quotation above omits internal quotations and citations.

I hear you Greg.

Any luck on pushing back on the examiner to explicate those findings?

(I mean of course, before one has to be dragged to the appeals stage)

Part of the problem here is the rampant reliance on In Re Jung by the PTO, far beyond the case itself. The PTO always takes a mile when given an inch.

I don’t think it’s reliance, rampant or otherwise, on Jung, or any other decision that’s the problem. That was an otherwise unremarkable case, but for Intellectual Ventures’s decision to tilt at windmills.

There are scores and scores of decisions that state quite clearly that the PTO’s decisions have to be based on objective evidence and the evidence and reasons for the decisions have to be clear from the record. The PTO ignores those decisions, all of them, when they are inconvenient to what the PTO wants the answer to be. For example, the claim doesn’t pass the pencil test, so it has to be rejected. No evidence to reject it? No matter. Just make something up and reject it. That’s the PTO’s understanding of “outstanding record breaking quality work.”

The PTO was taking a mile when given an inch long, long before In re Jung was decided.

A case on point re ordinary remand rule: National Association of Home Builders v. Defenders of Wildlife, 551 U.S. 644, 684 (2007) (The Court reversing the Ninth Circuit on the merits, determining that the EPA’s construction of the statute was reasonable and permissible, and then the Court chastises the lower (appeals) court for overstepping its authority in its review of the agency’s order). Although not binding precedent but instructive on the application of the ordinary remand rule: INS v. Ventura, 537 U.S. 12, 16 (2002) (per curiam) (stating proper course is to remand to agency)

What Judge Wallach was referring to is call the “ordinary remand rule”. The “ordinary remand” doctrine’s pedigree is based on a series of opinions issued in cases involving judicial review of an agency’s formal adjudications. See SEC v. Chenery Corp. (Chenery II), 332 U.S. 194, 196 (1947) (“[A] reviewing court . . . must judge the propriety of [agency] action solely by the grounds invoked by the agency.”); Chenery I, 318 U.S. at 87 (“The grounds upon which an administrative order must be judged are those upon which the record discloses that its action was based.”). But what is more interesting is that this rule applies not only questions of fact, but also mixed questions of law and fact, policy judgments, and even certain questions of law; see Negusie v. Holder, 555 U.S. 511, 520 (2009) (remanding question of statutory interpretation to the agency instead of providing an answer itself). The ordinary remand rule was reiterated in Federal Election Comm’n v. Akins, 524 U.S. 11, 25 (1998) (“If a reviewing court agrees that the agency misinterpreted the law, it will set aside the agency’s action and remand the case – even though the agency (like a new jury after a mistrial) might later, in the exercise of its lawful discretion, reach the same result for a different reason.”). It is important to note that the Federal Circuit does not follow the ordinary remand rule.

reply vanished into the wind…

So Judge Wallach meant something he didn’t say? I don’t think so.

Anyways, your analogies are misplaced. In this case, as in most PTO appeals, the issue was not one of statutory interpretation, but what to do when the evidence relied upon can not support the factual findings necessary under the undisputed interpretation of Section 102 or 103.

The logic underlying the “ordinary ‘remand’ rule” is that “an appellate court cannot intrude upon the domain which Congress has exclusively entrusted to an administrative agency,” (emphasis added. SEC v. Chenery Corp., 318 U.S. 80, 88 (1943); accord, INS v. Ventura, 537 U.S. 12, 16 (2002). In other words, there is a condition precedent before the “ordinary ‘remand’ rule” kicks in: the matter in question must have been entrusted to the exclusive purview of an administrative agency. That condition is not met here. The PTO has been entrusted with no discretion in matters of substantive patent law. Merck & Co. v. Kessler, 80 F.3d 1543, 1550 (Fed. Cir. 1996). Therefore, the “ordinary ‘remand’ rule” is simply inapposite to this case.

The PTO, at every level, feels entitled to unlimited “do overs” until they somehow get it right (i.e. write something that might actually could possibly be considered as “good enough” to justify the decision they wanna make anyway regardless of what the evidence and facts indicate otherwise). The court should not indulge them. If they get the facts wrong, they lose. Stop giving them do overs.

Quite right!

Hmm,

If I listen to Malcolm, the vast numbers of these repeated “do-overs” are in favor of applicants.

Why is it that I sense a conflict between your statement and Malcolm’s?

“The PTO is terrible at evaluating patent applications — except when they rule in my favor!! Then they are always right.”

Are you referring to this comment at 2.1.1 from MM in the “Rejection Perception” post?

“Just a friendly reminder of the basic facts: across the board, the PTO makes far far more errors in the applicant’s favor than not.”

If so, I don’t see anything in that post of his about “repeated do-overs.” He simply stated that the PTO makes far far more errors in applicants’ favor than not.

I don’t agree with him on that at all. Mostly because I know that there are zero negative consequences for an examiner, or SPE, or APJ, to incorrectly reject a claim, but there are negative consequences for incorrectly allowing a claim. So the default position of the PTO is to reject. Examiners do repeated do overs to reject the claims, not to allow them. Each do over is, on some level, an admission that the previous rejection was improper.

Yes, that post was the most recent of Malcolm’s (repeated) admonitions (whinings) that the applicants routinely get the benefit of the actions of the Office – with the clear message that any complaining of improper examination is unfounded whining.

There’s a reasonable for the do-overs.

Hint: it’s not all about you.

“Hint: it’s not all about you.”

The attempted point is too oblique.

what is it “about you” that ANYONE is attempting to insert as an argument here (or is this just a Malcolm strawman…)?

The results are pretty asymmetrical though, right? Although, contra MM’s suggestion, the PTO almost certainly makes more errors against applicants’ interests than in applicants’ favor, the result of an error in an applicant’s favor is often much harder to correct. The PTO can make five bad rejections in a case, but the applicant can keep asking for review of those errors.* If the PTO makes an error in allowing a case, a patent is going to issue which gets a presumption of validity.

Frequently, bad rejections and bad allowances are just two sides of the same coin. The common thread to both bad rejections and bad allowances is that if you don’t take the time to set forth and articulate a reasoned rejection, then it’s easy to get it wrong.

Examination is hard. Examiners have a hard job. PTO management has a hard job. But allowing boilerplate rejections with haphazard citations to portions of references not only enables bad actors to take advantage (I believe that this is the minority of examiners), but additionally can sometimes cause well-intentioned examiners to fail to appreciate some nuance because they didn’t have to actually articulate a logical rejection (and would be less productive than their fellow examiners who choose not to). Examination should not be a race to the bottom, where competing for productivity makes it hard for an examiner to justify spending a lot of time to articulate each rejection.

However, it seems tough to argue that just because an examiner failed to articulate a good rejection that necessarily means that a claim is automatically allowable. (Although there is some argument for incentivizing the PTO to improve examination quality.)

* Obviously, though, this costs an applicant resources, which should probably be considered.